Against “vertical” metaphysical relations

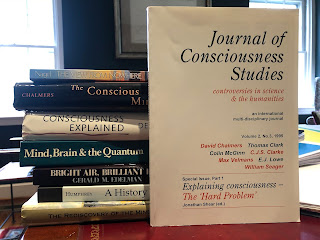

My first post in this recent series was prompted by reading Philip Goff’s book presenting his panpsychist approach to the problem of consciousness.1 In the sections where he addresses the combination problem, Goff considers alternative strategies for situating a macro-size conscious subject in the world: several of these involve appeals to “grounding”. To sketch, grounding (in its application to ontology) is a kind of non-causal explanatory metaphysical relation between entities, with things at a more fundamental “level” of reality typically providing a ground for something at a higher level. For example, a metaphysician fleshing out the notion of a physicalist view of reality might appeal to a grounding relationship between, say, fundamental simple micro-physical entities and bigger, more complex macro-size objects. It’s a way of working out the idea that the former account for the latter, or the latter exist in virtue of the former. There are a variety of ways to explicate this kind of idea.2 Goff presents a version called constitutive grounding. He thinks this faces difficulties in the case of accounting for macro-sized conscious subjects in terms of micro-sized ones, and discusses an alternative approach where the more fundamental thing is at the higher level: he endorses a view where the most fundamental conscious entity is, in fact, the entire cosmos (“cosmopsychism”). In this scenario, human and animal concsciousness can be accounted for via a relation to the cosmos called grounding by subsumption. Goff motivates these various notions of grounding with examples that appeal to how certain of our concepts seem to be linked together, or to how our visual experiences appear to be composed.

Please read the book for the details.3 Here, I want to comment on why I don’t find an approach like this to be very illuminating. It is actually a part of a more general methodological concern I have developed over time. Certainly, trying to uncover the metaphysical truth about things is always a somewhat quixotic endeavor! But I think it is extremely likely to go wrong when done via excavation of our intuitions in the absence of close engagement with the relevant sciences.4 To make a long story short, I’ll just say that here I concur with much of Ladyman and Ross’s infamous critique of analytic metaphysics.5 But to get more specific, I have a deep skepticism in particular about the whole notion of synchronic (“vertical”) metaphysical relations. Not only panpsychist discussions but a great many philosophy of mind debates are structured around the idea that ontological elements at different “levels” are connected by such relations as part-whole, supervenience, or grounding. Positing these vertical relations, in turn, has contributed to confusion in debates about notions of (ontological) reduction and emergence. The causal exclusion problem, I believe, is misguided to the extent it is premised in part on the existence of these vertical relations.

I see no evidence that there are any such synchronic relations in the actual world investigated by the natural sciences (although they may characterize some of our idealized models). At arbitrary infinitesimal moments of time there exist no relata to connect: there are no such things as organisms, brains, cells, or even molecules. All these phenomena are temporally extended dynamic processes. Any static conception we employ is an artifact of our cognitive apparatus or our representational schemes. Reifying these static conceptions and then drawing vertical lines between entities at different scales is a mistake. My view is that all relations of composition in nature are diachronic.

Solve the problem with a new metaphysics of causation?

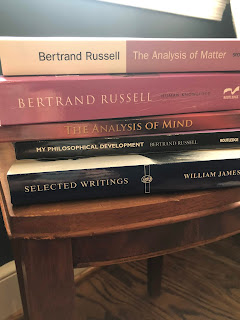

Given this, I think questions about how phenomena at different scales relate to each other involve a causal form of composition. So, one might ask whether thinking about the nature of causation help can with the problem of consciousness. Even before doing my own deep dive into research on the topic, I was drawn to those panpsychist approaches that explored this avenue. As mentioned in the earlier post, Russell’s account takes a causal approach to the structuring of subjects, although he himself doesn’t go on to offer a detailed theory.6 I think Whitehead’s speculative metaphysics can be characterized, at least in part, as an attempt to use a rich metaphysics of causation to account for the integration of mind and world. In more recent times, Gregg Rosenberg developed an account that found a home for consciousness in the nature of causation.7

Over time, however, I have also become skeptical of these more expansive causal theories. This is in spite of my view of the central role causation should play in any account of the composition of natural systems. Here, the problem is that these approaches go too far by baking in the answer to the mind-body problem from the beginning. Methodologically, I believe we should resist the urge to invent a causal theory that is so enriched with specific dualistic features that it directly addresses the challenge. For example, in Whitehead’s system every causal event (“actual occasion”) already has in place both a subjective and an objective “pole.” For Rosenberg, two kinds of properties (“effective” and “receptive”) are involved in each causal event, and this ultimately underpins the apparent dualism of the physical and mental. In contrast to these speculative solutions, we should be more conservative and pursue a causal theory that makes sense of our successful scientific explanations of natural phenomena, and then see how that effort might shed light on the mind. I’ll discuss my view on this in a future post.

1 Consciousness and Fundamental Reality. 2017. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

2 Here’s the SEP article on grounding.

3 Also, check out Daniel Stoljar’s review.

4 A quite different way metaphysics can go wrong is when those who are truly and deeply engaged with science (specifically physics) succumb to the tendency to (more or less) read ontology off of the mathematical formalism. But that is a discussion for another time.

5 Everything Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized. 2007. James Ladyman & Don Ross. Oxford: Oxford Univerisity Press. See. Ch 1.

6 At least this is true of The Analysis of Matter (1927), where the view now known as Russellian Monism was most fully developed. In his later Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits (1948), he presents a bit of a theory via his account of “causal lines:” specifically, this comes in the context of an argument that such a conception of causation is needed to account for successful scientific inferences (part VI, chapter V). As an aside: by this time, Russell seemed to come quite a long way toward a reversal of the arguments presented in his (much more cited) “On the Notion of Cause” from 1913. There, Russell argued that the prevailing philosophical view of cause and effect does not play a role in advanced sciences. Someone looking to harmonize the early and late Russell might argue that the disagreement between the two positions is limited: one could say the later Russell is developing causal notions that better suit the practice of science as compared to the more traditional concept that is the focus of criticism in the earlier article. However, I think it is clear that the later book’s perspective is quite a sea change from the earlier paper’s generally dismissive approach to the importance of causation to science.

7 A Place for Consciousness. 2004. Oxford: Oxford University Press. I have some older posts about the book.