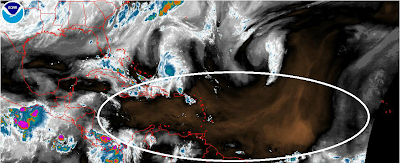

Early on October 15, 1987, an innocuous low-pressure system was moving across the Bay of Biscay off the west coast of France. Within one day, it became one of the most strongest windstorms in European history. Poorly anticipated, the storm produced hurricane-force sustained winds for hours over portions of Great Britain and France as well as absurdly strong gusts. The highest measured during the storm was 135 mph, corresponding to category 4 on the hurricane Saffir-Simpson scale (the cyclone was not tropical, however, so the word "hurricane" did not apply). Subsequently known simply as the "Great Storm of 1987," it prompted further study of the mechanisms by which extratropical storms produce extreme winds.

The above satellite image shows the Great Storm of 1987 with a long frontal "tail" extending all the way down to the Canary Islands.

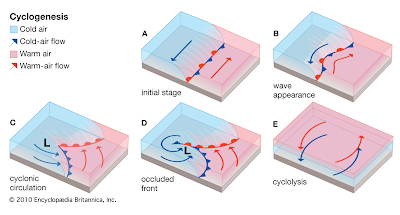

By the time of the Great Storm, the overall genesis process for extratropical cyclones was well understood. The energy for extratropical cyclone formation ultimately derives from temperature differences: cold air from the polar regions meets warm air from the subtropics, usually between 30 and 60 degrees latitude north and south. At these interfaces, there are differences in air pressure at the same altitude in the atmosphere since cold air is denser than warm. This instability provides the energy to drive cyclone formation.

Under the right circumstances, small perturbations in the flow along a boundary of air masses can trigger the formation of a low-pressure system, as indicated above. The cyclonically rotating boundaries between warm and cold air become the warm and cold fronts that control weather in the mid-latitudes. Note that all diagrams, including that above, are the correct orientations in the Northern Hemisphere: the directions of spin would be reversed south of the equator. Our concern in this post is investigating where the strongest surface winds occur in these extratropical storms.

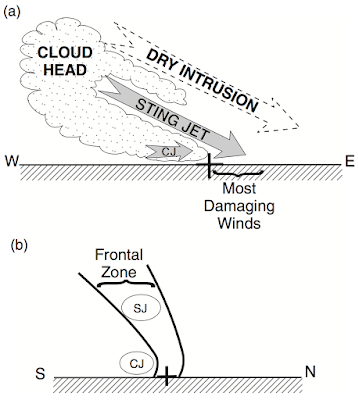

The above schematic shows major low-level winds associated with an extratropical cyclone at different stages of development. These are typical of a rapidly developing and strong storm, which is assumed to be moving northeast. As the storm ramps up, the dominant feature is the mild and wet Warm Conveyor Belt (WCB). This feeds the center a supply of moisture; indeed, nearly all the precipitation occurs ahead (east) of the advancing cold front boundary. Windy conditions can accompany the WCB, but they are not usually too extreme.

In the wake of the cold front comes the chilly and dry Cold Conveyor Belt (CCB). Most intense in a mature storm, this feature often packs stronger winds than the WCB, though they occur after precipitation has passed. Both of these are large-scale, well-understood features, but could not account for the unusually strong surface winds observed in some rapidly intensifying storms. It is the third feature above that fills in the gap: the so-called Sting Jet (SJ).

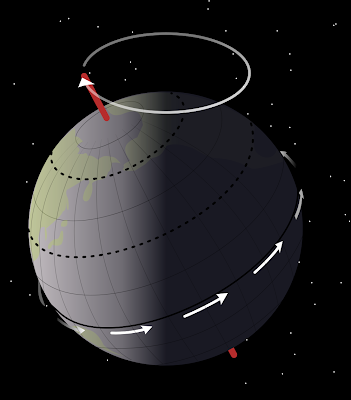

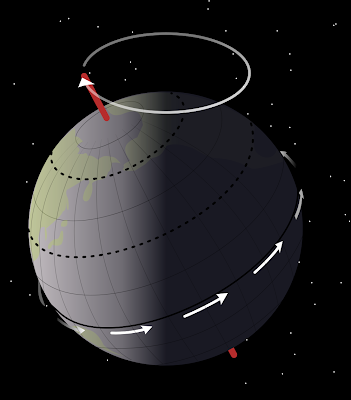

Named for the "sting at the end of the tail", the sting jet occurs near the very tip of the cloud head, where the bent-back cold front in the diagram above ends. This feature occurs most commonly in cyclones that explosively intensify or "bomb cyclones". The technical definition for this is a pressure drop of 24 mb or more in a period of 24 hours. As shown in the diagram below, just east of this "tail" of the cloud structure, instability causes dry air to descend from high in the atmosphere. Below this is the sting jet. It is a smaller feature compared to the CCB and WCB, about 100 km wide instead of several hundred. This conveyor belt of air is pushed toward the ground by the intruding dry air above.

Typically, friction with the land (or ocean) keeps winds near the surface lower than the strongest winds a few thousand feet above sea level. However, the descending site jet can transport these strong winds quickly to the surface. Moreover, the sting jet comes just head of the CCB (written CJ in the above picture) out of the south or southwest. In a cyclone moving northeast, these winds align with the storm's direction of motion, boosting them even higher. The result: localized but extremely intense wind gusts at the ground, associated with little to no precipitation.

Nearly all documented examples of sting jets are associated with north Atlantic storms impacting Europe. Since the Great Storm of 1987, roughly a dozen more examples have been positively identified. Satellite data indicate that further events likely occur over water where surface observations are sparse. Few studies have investigated the occurrence of sting jets elsewhere around the world, but explosive intensification of extratropical cyclones also occurs in the northwest Pacific and near Antarctica. Fortunately, comparable events in these regions have far fewer human impacts.

A thorough survey of the causes of sting jets is beyond the scope of this post; however, our understanding of this phenomenon is far from complete. Computer models struggle to resolve the feature, especially its tendency to "fan out" in to many small jets near the surface. As a result, predicting these events is still difficult. There is a lot on the line: the Great Storm of 1987 killed 22 people and caused billions in damages. Hopefully, future advances in advance warning will avert the worst impacts of these powerful storms.

Sources: https://journals.ametsoc.org/jcli/article/30/14/5455/97090/Sting-Jet-Windstorms-over-the-North-Atlantic, https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/weather/types-of-weather/wind/sting-jet, https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1256/qj.02.143, https://rams.atmos.colostate.edu/at540/fall03/fall03Pt5.pdf, https://www.britannica.com/science/cyclogenesis, https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/qj.3267

Showing posts with label Meteorology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Meteorology. Show all posts

Friday, January 1, 2021

Sunday, March 1, 2020

The Hurricane Graveyard

The Caribbean Sea appears to be a fertile area for the genesis and development of hurricanes: it lies at a tropical latitude, with warm ocean waters averaging over 80° F (26.7° C) for most of the year, including hurricane season (which extends from June to November). Warm water is essential to the development of hurricane, as it feeds warm moist air updrafts into burgeoning thunderstorms. However, during some hurricane seasons, the track map looks something like this:

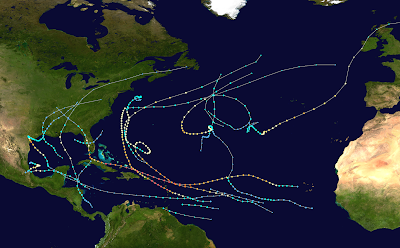

The above image shows the tracks of all the tropical cyclones during the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. Despite this season being extremely active and devastating, there is a "hole" in the map over the Caribbean, especially the eastern portion. No cyclones developed in 2017 in the eastern Caribbean and the ones that entered this region died out (though Harvey ultimately regenerated further west, with horrific consequences). This particular season was cherrypicked, but this phenomenon is sufficiently common and well-known to the meteorological community that the eastern Caribbean is sometimes known as the "Hurricane Graveyard".

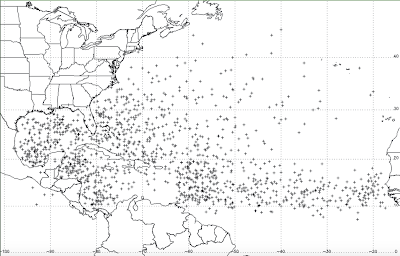

Statistics confirm that the Hurricane Graveyard is more than just weather lore. Consider the diagram below, which shows the point of genesis for all known "in-season" (June to November) tropical cyclones between 1851 and 2008:

It is clear that, relative to other areas at the same latitude, the eastern Caribbean churns out far fewer tropical cyclones. What is more, tropical cyclones often unexpectedly weaken or dissipate as they pass through it, contrary to the expectations of many computer models and forecasts (however, models do fairly well at predicting the scarcity of genesis in the eastern Caribbean, see this article). So why does the Hurricane Graveyard exist?

A 2010 study examined some the factors that contribute to this phenomenon. One of these is the Caribbean low-level jet (CLLJ). Low-level jets are channels of fast-moving air in the low levels of the atmosphere near the surface (analogous to jet streams, which are much stronger and at higher altitudes). The CLLJ blows east to west over the Caribbean, with the strongest winds occurring near its center, especially during July when the CLLJ reaches its peak. The winds moderate and reach a relative minimum by October, coinciding tellingly with a somewhat greater rate of tropical cyclone formation in the east Caribbean.

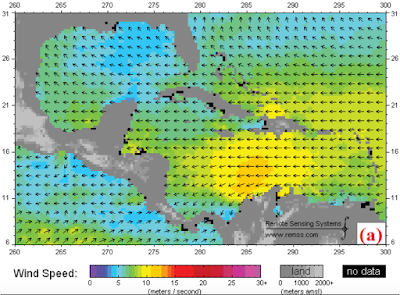

The above image shows the low-level winds in the Caribbean region averaged over the month July 2006. As the diagram indicates, wind speeds in excess of 10 m/s (22 mph) are typical during that time of year. These winds are due in part to the Azores-Bermuda high pressure system, a persistent area of dry, sinking air over the central subtropical Atlantic around which air flows clockwise. The southwestern portion of clockwise flow is evident in the diagram above. But why do horizontal winds of this sort inhibit tropical cyclone development? Further, the peak winds occur toward the center of the Caribbean, whereas our area of interest lies to the east, so what gives?

The key concept explaining the hurricane graveyard is low-level divergence. Divergence is simply a measure of to what degree air (or any fluid) is flowing out of a region. Two schematic vertical cross-sections of the atmosphere are shown below.

In the first, there is low-level divergence, as air is flowing outward from the central region. Since any outgoing air must be replaced, this air can only come from above, creating downdrafts and convergence (the opposite) at the atmosphere's upper levels. The reverse occurs in the second diagram. One may note that our diagram of Caribbean winds does not show air moving outward from any central point. However, the CLLJ accelerates moving east to west across the eastern portion of the sea, so it is still a situation where more air is leaving this region in the lower levels than is entering it. Hence the eastern Caribbean exhibits low-level divergence!

Crucially, low-level divergence is the opposite of what hurricanes need to thrive. Thunderstorm activity is driven by rising moist air and killed by sinking dry air. The divergence caused by the CCLJ often causes the thunderstorms associated with tropical cyclones or disturbances to collapse when they pass over the region, at last accounting for the Hurricane Graveyard.

Recent analyses have shed even more light on this phenomenon. It peaks in July when the CCLJ does, diminishing toward the end of hurricane season. Indeed, the rate of cyclonogenesis in the eastern Caribbean more closely resembles that of the rest of the basin from October onward. In addition, the Hurricane Graveyard effect is more pronounced in summers with an El Niño, when the Azores-Bermuda high is farther west and stronger, leading to a more powerful CCLJ. This effect illustrates how there is a great deal more to hurricane formation than humid air and warm water. Several other atmospheric factors, including low-level divergence, feature crucially in understanding and forecasting the development of tropical cyclones.

Sources: https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/2009BAMS2822.1, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/WAF-D-13-00008.1, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/2011JCLI4176.1, http://www.atmo.arizona.edu/students/courselinks/fall16/atmo336/lectures/sec1/winds_fall15.html

The above image shows the tracks of all the tropical cyclones during the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. Despite this season being extremely active and devastating, there is a "hole" in the map over the Caribbean, especially the eastern portion. No cyclones developed in 2017 in the eastern Caribbean and the ones that entered this region died out (though Harvey ultimately regenerated further west, with horrific consequences). This particular season was cherrypicked, but this phenomenon is sufficiently common and well-known to the meteorological community that the eastern Caribbean is sometimes known as the "Hurricane Graveyard".

Statistics confirm that the Hurricane Graveyard is more than just weather lore. Consider the diagram below, which shows the point of genesis for all known "in-season" (June to November) tropical cyclones between 1851 and 2008:

It is clear that, relative to other areas at the same latitude, the eastern Caribbean churns out far fewer tropical cyclones. What is more, tropical cyclones often unexpectedly weaken or dissipate as they pass through it, contrary to the expectations of many computer models and forecasts (however, models do fairly well at predicting the scarcity of genesis in the eastern Caribbean, see this article). So why does the Hurricane Graveyard exist?

A 2010 study examined some the factors that contribute to this phenomenon. One of these is the Caribbean low-level jet (CLLJ). Low-level jets are channels of fast-moving air in the low levels of the atmosphere near the surface (analogous to jet streams, which are much stronger and at higher altitudes). The CLLJ blows east to west over the Caribbean, with the strongest winds occurring near its center, especially during July when the CLLJ reaches its peak. The winds moderate and reach a relative minimum by October, coinciding tellingly with a somewhat greater rate of tropical cyclone formation in the east Caribbean.

The above image shows the low-level winds in the Caribbean region averaged over the month July 2006. As the diagram indicates, wind speeds in excess of 10 m/s (22 mph) are typical during that time of year. These winds are due in part to the Azores-Bermuda high pressure system, a persistent area of dry, sinking air over the central subtropical Atlantic around which air flows clockwise. The southwestern portion of clockwise flow is evident in the diagram above. But why do horizontal winds of this sort inhibit tropical cyclone development? Further, the peak winds occur toward the center of the Caribbean, whereas our area of interest lies to the east, so what gives?

The key concept explaining the hurricane graveyard is low-level divergence. Divergence is simply a measure of to what degree air (or any fluid) is flowing out of a region. Two schematic vertical cross-sections of the atmosphere are shown below.

In the first, there is low-level divergence, as air is flowing outward from the central region. Since any outgoing air must be replaced, this air can only come from above, creating downdrafts and convergence (the opposite) at the atmosphere's upper levels. The reverse occurs in the second diagram. One may note that our diagram of Caribbean winds does not show air moving outward from any central point. However, the CLLJ accelerates moving east to west across the eastern portion of the sea, so it is still a situation where more air is leaving this region in the lower levels than is entering it. Hence the eastern Caribbean exhibits low-level divergence!

Crucially, low-level divergence is the opposite of what hurricanes need to thrive. Thunderstorm activity is driven by rising moist air and killed by sinking dry air. The divergence caused by the CCLJ often causes the thunderstorms associated with tropical cyclones or disturbances to collapse when they pass over the region, at last accounting for the Hurricane Graveyard.

Recent analyses have shed even more light on this phenomenon. It peaks in July when the CCLJ does, diminishing toward the end of hurricane season. Indeed, the rate of cyclonogenesis in the eastern Caribbean more closely resembles that of the rest of the basin from October onward. In addition, the Hurricane Graveyard effect is more pronounced in summers with an El Niño, when the Azores-Bermuda high is farther west and stronger, leading to a more powerful CCLJ. This effect illustrates how there is a great deal more to hurricane formation than humid air and warm water. Several other atmospheric factors, including low-level divergence, feature crucially in understanding and forecasting the development of tropical cyclones.

Sources: https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/abs/10.1175/2009BAMS2822.1, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/WAF-D-13-00008.1, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/2011JCLI4176.1, http://www.atmo.arizona.edu/students/courselinks/fall16/atmo336/lectures/sec1/winds_fall15.html

Labels:

Meteorology

Saturday, February 1, 2020

Atmospheric Rivers

The transport of water vapor in the atmosphere is responsible for the world's weather. As such, tracking the movement of water-laden air masses is essential to weather forecasting. By the mid-1990's, satellite measurements had documented that the flow of moisture through the atmosphere often occurs in very high volumes through very narrow channels. These phenomena were named atmospheric rivers, because the amount of water they transport is comparable to that of Earth's largest rivers.

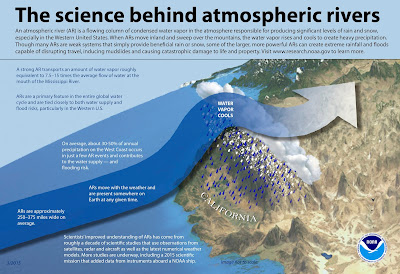

The above graphic (click to enlarge) summarizes the basics of atmospheric rivers. The most well-known example, as indicated above, delivers water vapor from near the equator to the western coast of north America, especially California. This phenomenon is the source of a large portion, if not a majority, of precipitation in these regions when moist air is forced upward over the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The formation of a specific atmospheric river event often occurs when a strong extratropical cyclone moves away from the equator toward higher latitudes, dragging warm equatorial air in its wake. This paper analyses the role such cyclones have in driving atmospheric rivers, focusing on a case study of a powerful February 2002 cyclone. This cyclone formed in the north Atlantic and moved northeastward, passing west of the British Isles before ultimately dissipating in the Barents Sea north of Scandinavia. At its peak intensity, it bottomed out at 935 mb, a pressure comparable to that of a category 4 hurricane!

The above shows the cloud pattern of the cyclone on an infrared satellite view (top) and a diagram showing total column water vapor (TCWV, bottom) in the same region. Unlike for hurricanes, most of the extratropical storm's water vapor is concentrated in a linear feature far from the center and extending south and west. The counterclockwise rotation of the large circulation in the northern hemisphere draws a long train of warm, tropical air northward, and it is here that the atmospheric river sets up.

In practice, meteorologists detect atmospheric rivers using satellite imagery, which can detect the transport of water vapor in the atmosphere, and the threshold for being an atmospheric river depends on the integrated water vapor transport (IVT) value in a given region. This is calculated by adding up the flow of moisture in different layers of the atmosphere. Using these tools, the frequency/severity of such events across the world has recently been analyzed.

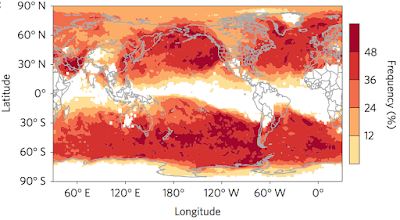

The above map shows the percentage of severe surface precipitation events are associated with atmospheric rivers in different locations across the world over the period 1997-2014. Only precipitation events ranking in the top 2% for a given region are considered. Therefore, the map shows where atmospheric rivers have the greatest impact: mostly over the ocean, but also in portions of western North America, southern South America, central Asia, and eastern Australia. They also are associated with extreme wind events over many of the same regions. As a result, atmospheric rivers are responsible for many of the most damaging flooding events across the globe. Better understanding their formation and evolution will improve our ability to forecast and respond to flooding events in the future.

Sources: https://web.archive.org/web/20100610035058/http://paos.colorado.edu/~dcn/ATOC6020/papers/AtmosphericRivers_94GL01710.pdf, https://noaa.gov, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00031.1, http://cw3e.ucsd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/WaliserGuan-ngeo2894.pdf

The above graphic (click to enlarge) summarizes the basics of atmospheric rivers. The most well-known example, as indicated above, delivers water vapor from near the equator to the western coast of north America, especially California. This phenomenon is the source of a large portion, if not a majority, of precipitation in these regions when moist air is forced upward over the Sierra Nevada mountains.

The formation of a specific atmospheric river event often occurs when a strong extratropical cyclone moves away from the equator toward higher latitudes, dragging warm equatorial air in its wake. This paper analyses the role such cyclones have in driving atmospheric rivers, focusing on a case study of a powerful February 2002 cyclone. This cyclone formed in the north Atlantic and moved northeastward, passing west of the British Isles before ultimately dissipating in the Barents Sea north of Scandinavia. At its peak intensity, it bottomed out at 935 mb, a pressure comparable to that of a category 4 hurricane!

The above shows the cloud pattern of the cyclone on an infrared satellite view (top) and a diagram showing total column water vapor (TCWV, bottom) in the same region. Unlike for hurricanes, most of the extratropical storm's water vapor is concentrated in a linear feature far from the center and extending south and west. The counterclockwise rotation of the large circulation in the northern hemisphere draws a long train of warm, tropical air northward, and it is here that the atmospheric river sets up.

In practice, meteorologists detect atmospheric rivers using satellite imagery, which can detect the transport of water vapor in the atmosphere, and the threshold for being an atmospheric river depends on the integrated water vapor transport (IVT) value in a given region. This is calculated by adding up the flow of moisture in different layers of the atmosphere. Using these tools, the frequency/severity of such events across the world has recently been analyzed.

The above map shows the percentage of severe surface precipitation events are associated with atmospheric rivers in different locations across the world over the period 1997-2014. Only precipitation events ranking in the top 2% for a given region are considered. Therefore, the map shows where atmospheric rivers have the greatest impact: mostly over the ocean, but also in portions of western North America, southern South America, central Asia, and eastern Australia. They also are associated with extreme wind events over many of the same regions. As a result, atmospheric rivers are responsible for many of the most damaging flooding events across the globe. Better understanding their formation and evolution will improve our ability to forecast and respond to flooding events in the future.

Sources: https://web.archive.org/web/20100610035058/http://paos.colorado.edu/~dcn/ATOC6020/papers/AtmosphericRivers_94GL01710.pdf, https://noaa.gov, https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/BAMS-D-14-00031.1, http://cw3e.ucsd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/WaliserGuan-ngeo2894.pdf

Labels:

Meteorology

Wednesday, January 1, 2020

Upper Atmospheric Clouds

Weather is caused by the atmosphere. However, most of what we know as weather is limited to the atmosphere's lowest layer, the troposphere. The height of the troposphere varies with latitude on the Earth, from under 4 miles (6 km) in the coldest polar regions to over 10 miles (16 km) at the equator. The distinguishing feature of this layer that allows weather to occur is cloud formation.

Cloud formation occurs when water, evaporated from the ground into gaseous water vapor, condenses into small water droplets in the atmosphere. However, the water vapor-laden air must have some means by which it is transported upward. One such means is orthographic cloud formation.

This occurs when the wind direction pushes air up the slope of a topographical feature such as a mountain. As air rises, it expands and cools. Since cooler air holds less water vapor, condensation begins, clouds form, and precipitation can follow. Another impact of this process is that the opposite side of the mountain from the prevailing wind can be very dry.

However, clouds of course also form in the absence of mountainous terrain. This occurs when a parcel of air near the surface, containing evaporated water, is heated by the warm sunlit ground. Warmer than the adjacent atmosphere, it rises. As the air rises, its pressure drops in accord with that of its surroundings (air pressure decreases with altitude, a phenomenon mountain climbers are familiar with). By the ideal gas law, the pressure of a gas is proportional to its temperature. Therefore, a rising parcel of air cools.

The tallest clouds form in the case of absolute instability, illustrated above (click to enlarge). The parcel of air begins at the ground at a temperature of 40° C. As it rises, it cools. However, in the unstable case, the air temperature of the ambient atmosphere drops more quickly than the temperature in the rising parcel of air (the rate of its cooling is known as the dry adiabatic lapse rate). As a result, the cooling air nevertheless remains warmer than its surroundings and continues to rise. Eventually, its becomes too cold to hold all of the water vapor and condensation begins at the condensation level. Condensation releases heat to the atmosphere, so the temperature decrease of the parcel slows (to what is known as the wet adiabatic lapse rate). The resulting condensation forms a cloud, whose lower extremity is the condensation level.

At the top of the above diagram, the parcel temperature is still much higher than the atmospheric temperature, so the air rises yet more, continuing to increase the height of the cloud on the way. In situations such as this, a cumulonimbus cloud may form.

Cumulonimbus can extend from a few thousand feet from the ground over 10 miles (16 km) upward. It is these clouds that are responsible for many types of extreme weather, including severe thunderstorms, hail, and even tornadoes. However, even for these enormous clouds, there is an limit to their upward growth: the tropopause. The tropopause is the boundary between the troposphere below and the next layer of the atmosphere, the stratosphere, above. As indicated at the beginning of the post, the height of the tropopause varies with latitude. It is characterized by a reversal of the decline in temperature with height that takes place up to this point. Beginning at the tropopause and into the stratosphere, temperature again begins to increase with height (as shown near the bottom of the figure below).

Unlike in the troposphere, where the only significant source of heat was the sun-heated surface below, the stratosphere derives heat from another source: the absorption of solar ultraviolet radiation by the ozone layer. Oxygen and ozone (O3) molecules interact with incoming ultraviolet rays, impeding their passage to the Earth's surface and therefore protecting it from most of this harmful radiation. In the process, they absorb heat. The result of all this is that air just above the tropopause is always stable: temperature increases with height. Rising parcels of air do not penetrate much past this point. Rather, they spread out laterally, forming the anvil top characteristic of cumulonimbus clouds and illustrated above. By virtue of their momentum, a few parcels enter a bit into the stratosphere; this is the "overshooting top" in the diagram.

However, in rare cases, clouds can form outside the troposphere. For example, polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) may sometimes form in high latitude regions. They occur in the lower stratosphere, at altitudes varying from 6 to 15 miles (10-25 km), where temperatures plummet to below -100° F. At these especially low temperatures, water vapor can condense directly into ice crystals. The more spectacular PSCs are the nacreous clouds, which are composed entirely of these crystals. They are most visible just after sunset when the Sun has disappeared below the horizon on the ground but still illuminates the stratosphere. The ice crystals diffract light, producing beautiful iridescent displays.

This image shows nacreous clouds over McMurdo Station, Antarctica. Though they are most often seen over that continent, they also appear occasionally over northern Europe, North America, and Russia. PSCs are of scientific interest because they can serve as sites for chemical reactions that destroy ozone. Understanding the climatology of these unusual clouds helps to monitor the regional variation of ozone in polar regions.

In addition to PSCs, there is another type of upper atmospheric cloud that occurs even at even higher altitudes. Noctilucent clouds, so named because they are only visible at night well after the Sun has passed below the horizon, form in the mesosphere. This layer is defined as being the second region where temperature decreases with height. The clouds form generally around 50 miles (80 km) above the surface. Though not fully understood, it is thought the formation of noctilucent clouds is due to meteoric dust. This dust is the result of small objects from space breaking up upon entering Earth's atmosphere and serves as a site for the formation of ice crystals. Though the amount of moisture water vapor this high is minuscule, the temperature here can plummet to a frigid -180° F at high latitudes, supporting ice crystal formation.

The above image, taken from Nunivak Island, Alaska, shows noctilucent clouds after sunset. These clouds are at such a high altitude that they reflect sunlight from below the horizon back down to Earth. Studying the locations where these clouds form can reveal concentrations of dust (meteoric or from other sources such as volcanoes) in the mesosphere as well as shed light on how the upper atmosphere changes with the climate. Apart from their scientific value, upper atmospheric clouds join the aurorae as some of the most beautiful displays to be found in polar skies.

Sources: The Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate Change by Juliane Fry, https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/Methane-Giving-Noctilucent-Clouds-Boost?cm_ven=hp-slot-1, http://www.richhoffmanclass.com/chapter4.html, https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/science/atmosphere-layers2.html, https://www.atoptics.co.uk, https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_680.html, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/04/140411091939.htm

Cloud formation occurs when water, evaporated from the ground into gaseous water vapor, condenses into small water droplets in the atmosphere. However, the water vapor-laden air must have some means by which it is transported upward. One such means is orthographic cloud formation.

This occurs when the wind direction pushes air up the slope of a topographical feature such as a mountain. As air rises, it expands and cools. Since cooler air holds less water vapor, condensation begins, clouds form, and precipitation can follow. Another impact of this process is that the opposite side of the mountain from the prevailing wind can be very dry.

However, clouds of course also form in the absence of mountainous terrain. This occurs when a parcel of air near the surface, containing evaporated water, is heated by the warm sunlit ground. Warmer than the adjacent atmosphere, it rises. As the air rises, its pressure drops in accord with that of its surroundings (air pressure decreases with altitude, a phenomenon mountain climbers are familiar with). By the ideal gas law, the pressure of a gas is proportional to its temperature. Therefore, a rising parcel of air cools.

The tallest clouds form in the case of absolute instability, illustrated above (click to enlarge). The parcel of air begins at the ground at a temperature of 40° C. As it rises, it cools. However, in the unstable case, the air temperature of the ambient atmosphere drops more quickly than the temperature in the rising parcel of air (the rate of its cooling is known as the dry adiabatic lapse rate). As a result, the cooling air nevertheless remains warmer than its surroundings and continues to rise. Eventually, its becomes too cold to hold all of the water vapor and condensation begins at the condensation level. Condensation releases heat to the atmosphere, so the temperature decrease of the parcel slows (to what is known as the wet adiabatic lapse rate). The resulting condensation forms a cloud, whose lower extremity is the condensation level.

At the top of the above diagram, the parcel temperature is still much higher than the atmospheric temperature, so the air rises yet more, continuing to increase the height of the cloud on the way. In situations such as this, a cumulonimbus cloud may form.

Cumulonimbus can extend from a few thousand feet from the ground over 10 miles (16 km) upward. It is these clouds that are responsible for many types of extreme weather, including severe thunderstorms, hail, and even tornadoes. However, even for these enormous clouds, there is an limit to their upward growth: the tropopause. The tropopause is the boundary between the troposphere below and the next layer of the atmosphere, the stratosphere, above. As indicated at the beginning of the post, the height of the tropopause varies with latitude. It is characterized by a reversal of the decline in temperature with height that takes place up to this point. Beginning at the tropopause and into the stratosphere, temperature again begins to increase with height (as shown near the bottom of the figure below).

Unlike in the troposphere, where the only significant source of heat was the sun-heated surface below, the stratosphere derives heat from another source: the absorption of solar ultraviolet radiation by the ozone layer. Oxygen and ozone (O3) molecules interact with incoming ultraviolet rays, impeding their passage to the Earth's surface and therefore protecting it from most of this harmful radiation. In the process, they absorb heat. The result of all this is that air just above the tropopause is always stable: temperature increases with height. Rising parcels of air do not penetrate much past this point. Rather, they spread out laterally, forming the anvil top characteristic of cumulonimbus clouds and illustrated above. By virtue of their momentum, a few parcels enter a bit into the stratosphere; this is the "overshooting top" in the diagram.

However, in rare cases, clouds can form outside the troposphere. For example, polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) may sometimes form in high latitude regions. They occur in the lower stratosphere, at altitudes varying from 6 to 15 miles (10-25 km), where temperatures plummet to below -100° F. At these especially low temperatures, water vapor can condense directly into ice crystals. The more spectacular PSCs are the nacreous clouds, which are composed entirely of these crystals. They are most visible just after sunset when the Sun has disappeared below the horizon on the ground but still illuminates the stratosphere. The ice crystals diffract light, producing beautiful iridescent displays.

This image shows nacreous clouds over McMurdo Station, Antarctica. Though they are most often seen over that continent, they also appear occasionally over northern Europe, North America, and Russia. PSCs are of scientific interest because they can serve as sites for chemical reactions that destroy ozone. Understanding the climatology of these unusual clouds helps to monitor the regional variation of ozone in polar regions.

In addition to PSCs, there is another type of upper atmospheric cloud that occurs even at even higher altitudes. Noctilucent clouds, so named because they are only visible at night well after the Sun has passed below the horizon, form in the mesosphere. This layer is defined as being the second region where temperature decreases with height. The clouds form generally around 50 miles (80 km) above the surface. Though not fully understood, it is thought the formation of noctilucent clouds is due to meteoric dust. This dust is the result of small objects from space breaking up upon entering Earth's atmosphere and serves as a site for the formation of ice crystals. Though the amount of moisture water vapor this high is minuscule, the temperature here can plummet to a frigid -180° F at high latitudes, supporting ice crystal formation.

The above image, taken from Nunivak Island, Alaska, shows noctilucent clouds after sunset. These clouds are at such a high altitude that they reflect sunlight from below the horizon back down to Earth. Studying the locations where these clouds form can reveal concentrations of dust (meteoric or from other sources such as volcanoes) in the mesosphere as well as shed light on how the upper atmosphere changes with the climate. Apart from their scientific value, upper atmospheric clouds join the aurorae as some of the most beautiful displays to be found in polar skies.

Sources: The Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate Change by Juliane Fry, https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/Methane-Giving-Noctilucent-Clouds-Boost?cm_ven=hp-slot-1, http://www.richhoffmanclass.com/chapter4.html, https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/science/atmosphere-layers2.html, https://www.atoptics.co.uk, https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_680.html, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/04/140411091939.htm

Labels:

Meteorology

Tuesday, February 12, 2019

Ocean Currents and the Thermohaline Circulation

Ocean currents are ubiquitous and familiar. Beach goers are wary of tidal currents, as well as those caused by weather systems. Currents caused by tides and weather are constantly changing and chaotic. However, under this noise exists a larger-scale and more orderly system of circulation. By averaging over long time periods (in effect screening out the noise of short-term fluctuations), larger currents such as the Gulf Stream, which brings warm water northward along the east coast of the United States, appear. Another example is the California current, which brings the cold waters of the north Pacific down along the west coast. But why do these currents exist? Some patterns may be seen if we expand our view to the world as a whole.

The above image shows major surface ocean currents around the world. Note that despite geographical differences, some currents in each ocean in each hemisphere follow the same general pattern, flowing east to west in the tropical latitudes, toward the poles on the western edge of ocean basins, west to east at mid-latitudes, and finally toward the equator on the eastern edges. These circular currents are known as subtropical gyres. For example, the Gulf Stream is the western poleward current in the north Atlantic subtropical gyre and the California current the eastern current toward the equator in the north Pacific tropical gyre. These exist largely due to the Earth's prevailing winds.

The prevailing winds at the Earth's surface fit into a larger dynamic atmospheric pattern. The greater heating of the tropics as compared to the polar regions and the rotation of the Earth lead to the formation of three atmospheric cells in each hemisphere. The winds in these cells rotate due to the Coriolis effect (in essence the fact that straight paths appear to curve from the viewpoint of an observer on a rotating planet), producing east to west winds in the tropics and polar regions, and west to east winds in the mid-latitudes. Look back at the subtropical gyres on the map of currents. Notice that the currents labeled "equatorial" follow the trade winds, and the north Pacific, north Atlantic, etc. currents follow the prevailing westerlies. The west and east boundary currents then "complete the circle" and close the flow. This is no coincidence. It is friction between air and water that drives subtropical gyres: the force of wind tends to make water flow in the same direction. Another important example is the Antarctic circumpolar current, the largest in the world. Since there are no landmasses between roughly 50°S and 60°S latitude, the westerlies drive a current unimpeded that stretches all the way around the continent of Antarctica. Many other currents in the global diagram are responses to these main gyres, or are connected to prevailing winds in more complicated ways.

This system of ocean currents has profound impacts on weather and climate. Due to the Gulf Stream, north Atlantic current, and its northern extension, the Norwegian current, temperatures in northwestern Europe are several degrees warmer than they would otherwise be.

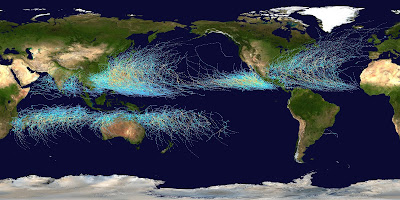

The above image illustrates one of the influences of ocean currents on weather. It shows all tropical cyclone tracks (hurricanes, typhoons, etc.) worldwide from 1985-2005. Since tropical cyclones need warm ocean surface waters to develop, the cold California current helps to suppress eastern Pacific hurricanes north of 25° N or so. In contrast, the warm Kuroshio current in the western Pacific allows typhoons to regularly affect Japan, which is at a higher latitude. Note also the presence of cyclones in the southwest Pacific and the lack of any formation in the southeast Pacific (though very cold surface waters are only one of several factors in this).

Despite their vast impact, which goes well beyond the examples listed, all of the currents considered so far are surface currents. Typically, these currents exist only in the top kilometer of the ocean, and the picture below this can look quite different.

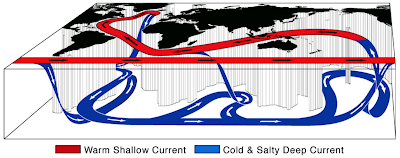

The above image gives a very schematic illustration of the global three-dimensional circulation of the oceans, known as the thermohaline circulation. The first basic fact about this circulation, especially the deep ocean circulation, is that it is slow. Narrow, swift surface currents such as the Gulf Stream have speeds up to 250 cm/s. Even the slower eastern boundary currents often manage 10 cm/s. In contrast, deep ocean currents seldom exceed 1 cm/s. Their tiny speed and remoteness makes them extremely difficult to measure; in fact, rather than directly charting their course, the flow is inferred from quantities called "tracers" in water samples. Measurements of the proportion of certain radioactive isotopes, for example, are used to calculate the last time a given water sample "made contact" with the atmosphere.

The above graphic illustrates the age of deep ocean water around the world. The age (in years) is how long it has been since a given water parcel came to equilibrium with the surface. Note that the thermohaline circulation occurs on timescales of over 1000 years. This information indicates that deep water formation (when water from the surface sinks) takes place in the North Atlantic but not the North Pacific, as indicated in the first graphic. This is because all the deep waters of the Pacific are quite "old". Deep water formation also occurs in the Southern Ocean, near Antarctica. In both cases, the mechanism is similar: exposure to frigid air near the poles makes the surface waters very cold, and therefore dense. Further, in winter, sea ice forms in these cold waters, leaving saltier water behind (since freshwater was "taken away" to form sea ice). This salty, cold water is denser than the ocean around it and it sinks. The newly formed deep water can flow near the bottom of the ocean for hundreds of years before coming back to the surface.

One climatological influence of this phenomenon is the ocean's increased ability to take up carbon dioxide. Most of the carbon dioxide emitted by human industry since the late 1800s has dissolved in the oceans. Since deep water takes so long to circulate, increased CO2 levels are only now beginning to penetrate the deep ocean. Most ocean water has not "seen" the anthropogenic CO2 so it will continue to take up more of the gas for hundreds of years. Without this, there would much more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and likely faster global warming.

The network of mechanisms driving ocean currents and the thermohaline circulation is quite intricate, and we have only touched on some of them here: weather systems, prevailing winds, differences in density, etc. There are many more subtleties as to why the ocean circulates the way it does. The study of these nuances is essential for fully understanding the Earth's weather and climate.

Sources: Atmosphere, Ocean, and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text by John Marshall and R. Alan Plumb, https://www.britannica.com/science/ocean-current, http://www.seos-project.eu/modules/oceancurrents/oceancurrents-c01-p03.html

The above image shows major surface ocean currents around the world. Note that despite geographical differences, some currents in each ocean in each hemisphere follow the same general pattern, flowing east to west in the tropical latitudes, toward the poles on the western edge of ocean basins, west to east at mid-latitudes, and finally toward the equator on the eastern edges. These circular currents are known as subtropical gyres. For example, the Gulf Stream is the western poleward current in the north Atlantic subtropical gyre and the California current the eastern current toward the equator in the north Pacific tropical gyre. These exist largely due to the Earth's prevailing winds.

The prevailing winds at the Earth's surface fit into a larger dynamic atmospheric pattern. The greater heating of the tropics as compared to the polar regions and the rotation of the Earth lead to the formation of three atmospheric cells in each hemisphere. The winds in these cells rotate due to the Coriolis effect (in essence the fact that straight paths appear to curve from the viewpoint of an observer on a rotating planet), producing east to west winds in the tropics and polar regions, and west to east winds in the mid-latitudes. Look back at the subtropical gyres on the map of currents. Notice that the currents labeled "equatorial" follow the trade winds, and the north Pacific, north Atlantic, etc. currents follow the prevailing westerlies. The west and east boundary currents then "complete the circle" and close the flow. This is no coincidence. It is friction between air and water that drives subtropical gyres: the force of wind tends to make water flow in the same direction. Another important example is the Antarctic circumpolar current, the largest in the world. Since there are no landmasses between roughly 50°S and 60°S latitude, the westerlies drive a current unimpeded that stretches all the way around the continent of Antarctica. Many other currents in the global diagram are responses to these main gyres, or are connected to prevailing winds in more complicated ways.

This system of ocean currents has profound impacts on weather and climate. Due to the Gulf Stream, north Atlantic current, and its northern extension, the Norwegian current, temperatures in northwestern Europe are several degrees warmer than they would otherwise be.

The above image illustrates one of the influences of ocean currents on weather. It shows all tropical cyclone tracks (hurricanes, typhoons, etc.) worldwide from 1985-2005. Since tropical cyclones need warm ocean surface waters to develop, the cold California current helps to suppress eastern Pacific hurricanes north of 25° N or so. In contrast, the warm Kuroshio current in the western Pacific allows typhoons to regularly affect Japan, which is at a higher latitude. Note also the presence of cyclones in the southwest Pacific and the lack of any formation in the southeast Pacific (though very cold surface waters are only one of several factors in this).

Despite their vast impact, which goes well beyond the examples listed, all of the currents considered so far are surface currents. Typically, these currents exist only in the top kilometer of the ocean, and the picture below this can look quite different.

The above image gives a very schematic illustration of the global three-dimensional circulation of the oceans, known as the thermohaline circulation. The first basic fact about this circulation, especially the deep ocean circulation, is that it is slow. Narrow, swift surface currents such as the Gulf Stream have speeds up to 250 cm/s. Even the slower eastern boundary currents often manage 10 cm/s. In contrast, deep ocean currents seldom exceed 1 cm/s. Their tiny speed and remoteness makes them extremely difficult to measure; in fact, rather than directly charting their course, the flow is inferred from quantities called "tracers" in water samples. Measurements of the proportion of certain radioactive isotopes, for example, are used to calculate the last time a given water sample "made contact" with the atmosphere.

The above graphic illustrates the age of deep ocean water around the world. The age (in years) is how long it has been since a given water parcel came to equilibrium with the surface. Note that the thermohaline circulation occurs on timescales of over 1000 years. This information indicates that deep water formation (when water from the surface sinks) takes place in the North Atlantic but not the North Pacific, as indicated in the first graphic. This is because all the deep waters of the Pacific are quite "old". Deep water formation also occurs in the Southern Ocean, near Antarctica. In both cases, the mechanism is similar: exposure to frigid air near the poles makes the surface waters very cold, and therefore dense. Further, in winter, sea ice forms in these cold waters, leaving saltier water behind (since freshwater was "taken away" to form sea ice). This salty, cold water is denser than the ocean around it and it sinks. The newly formed deep water can flow near the bottom of the ocean for hundreds of years before coming back to the surface.

One climatological influence of this phenomenon is the ocean's increased ability to take up carbon dioxide. Most of the carbon dioxide emitted by human industry since the late 1800s has dissolved in the oceans. Since deep water takes so long to circulate, increased CO2 levels are only now beginning to penetrate the deep ocean. Most ocean water has not "seen" the anthropogenic CO2 so it will continue to take up more of the gas for hundreds of years. Without this, there would much more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and likely faster global warming.

The network of mechanisms driving ocean currents and the thermohaline circulation is quite intricate, and we have only touched on some of them here: weather systems, prevailing winds, differences in density, etc. There are many more subtleties as to why the ocean circulates the way it does. The study of these nuances is essential for fully understanding the Earth's weather and climate.

Sources: Atmosphere, Ocean, and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text by John Marshall and R. Alan Plumb, https://www.britannica.com/science/ocean-current, http://www.seos-project.eu/modules/oceancurrents/oceancurrents-c01-p03.html

Labels:

Meteorology

Sunday, February 12, 2017

Rainbows

Rainbows are among the most recognizable of atmospheric phenomena. They appear in situations in which there are water droplets in the air during a period of sunshine. As a result, they commonly occur after rainstorms. Before exploring the properties of rainbows, we cover atmospheric optics in the absence of water droplets. This situation is dominated by Rayleigh scattering, which makes our sky blue.

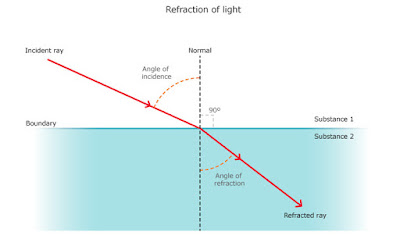

Rayleigh scattering of the sun's rays occurs when sunlight strikes air molecules. Higher frequencies of light (green, blue, violet) are more readily scattered than lower ones (red, orange, yellow) so when we look at the sky away from the Sun, most of what we see is scattered blue light. The interaction of sunlight with much larger water droplets is categorically different. Instead of scattering, light traveling from air to water (or for that matter, across the boundary of any two different media) is refracted.

This means that the angle of the light ray to the normal (the perpendicular to the boundary between media) changes as it passes from one to another. The origin of this effect is the fact that light travels at different speeds through different media. The extent to which this occurs for different substances is measured by a medium's index of refraction, often denoted n. If two media have indices of refraction n1 and n2 then the angles of the light rays to the normal within each (denoted θ1 and θ2) are given by Snell's Law:

n1sinθ1 = n2sinθ2

For air and water, the indices take values nair = 1.000293 and nwater = 1.330. Snell's Law then yields the fact that light rays bend toward the normal as they pass from air to water and do the opposite upon exiting. However, these values of the indices of refraction are for a specific wavelength of light (actually a standard color of yellow light emitted from excited atoms of sodium with a wavelength of 589.3 nm). The degree of refraction varies slightly across the visible wavelengths, leading to the separation of colors that we observe as a rainbow. The small droplets of water in the atmosphere are roughly spheres, leading to the kind of refraction illustrated below:

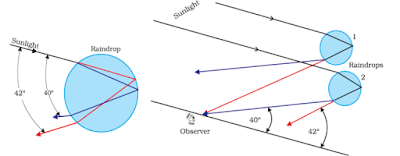

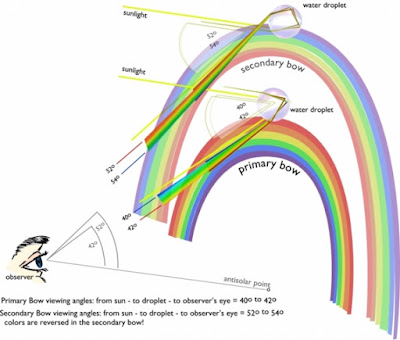

Note that the angles by which the light rays are refracted depends on where it hits the drop (the redness of the lines has no significance in this image) since the boundary between water and air is spherical, rather than flat. Each of the rays shown undergoes a single internal reflection before emerging from the water droplet, though some light just passes through, and some is internally reflected multiple times (more on this later). However, the maximum angle between the incoming and outgoing rays are different for different colors of light: in particular, they are greater for longer wavelengths than shorter. Therefore, at the very highest angles, the colors are separated.

At one end of the spectrum, violet light has a maximum angle of 40° from the incoming light ray, while in the longest visible wavelengths, red light has a maximum angle of 42° (left). As a result, for a fixed observer, red light will appear to come from a certain angle in the sky, while violet will appear to come from another (right). Orange, yellow, green, blue, and indigo will appear in between. The result is what we see as a rainbow.

Several properties of rainbows follow directly from this understanding. The first is that all (primary) rainbows are of the same angular size in the sky, namely 42° in radius. A rainbow therefore does not have a fixed position and appears the same size to every observer, meaning that every observer in fact sees their own rainbow. Also, the center of the rainbow's circular arc must be opposite to the position of the Sun in the sky. This point is called the anti-solar point and must always be below the horizon (since the Sun is above). As a result, the higher the Sun is in the sky, the lower the (primary rainbow). If the Sun is more than 42° above the horizon, it cannot be seen at all. This is why rainbows are typically seen early in the morning or later in the afternoon. In addition, though the maximum angle is 40-42° for different colors of light, some light (of all colors) is reflected from raindrops at smaller angles, making the sky just inside the rainbow noticeably brighter. This effect is apparent in the image above.

Though most light reflected within the raindrop undergoes only a single internal reflection, some is in fact reflected more than once, leading to what are known as higher-order rainbows, notably the secondary rainbow.

The colors of the secondary rainbow are reversed since an additional reflection inside the drop reverses the color spread. Further, it is situated at 52°, outside the primary rainbow, and is considerably fainter.

The secondary rainbow is sometimes too faint to be visible, but it is always there. In fact, light can reflect internally even more, producing higher-order rainbows. However, three reflections sends the light on a path at about 43° inclined from its original trajectory, meaning that it would form a circle of this radius around the Sun. Due to its faintness and proximity to the Sun, it is very difficult to photograph, but photographs have recently captured this phenomenon (see below).

Thus, a simple application of atmospheric optics may explain the rainbow, the beauty of which has captivated humanity since antiquity.

Sources: http://www.atoptics.co.uk/rainbows/primary.htm, http://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/refrn/Lesson-4/Rainbow-Formation, http://0.tqn.com/d/weather/1/S/j/T/-/-/water-drop-prism-lrg_nasascijinks.png, http://ephy.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/clip_image0061.png, http://www.nilvalls.com/supernumerary-rainbow/, http://www.atoptics.co.uk/rainbows/ord34.htm

Rayleigh scattering of the sun's rays occurs when sunlight strikes air molecules. Higher frequencies of light (green, blue, violet) are more readily scattered than lower ones (red, orange, yellow) so when we look at the sky away from the Sun, most of what we see is scattered blue light. The interaction of sunlight with much larger water droplets is categorically different. Instead of scattering, light traveling from air to water (or for that matter, across the boundary of any two different media) is refracted.

This means that the angle of the light ray to the normal (the perpendicular to the boundary between media) changes as it passes from one to another. The origin of this effect is the fact that light travels at different speeds through different media. The extent to which this occurs for different substances is measured by a medium's index of refraction, often denoted n. If two media have indices of refraction n1 and n2 then the angles of the light rays to the normal within each (denoted θ1 and θ2) are given by Snell's Law:

n1sinθ1 = n2sinθ2

For air and water, the indices take values nair = 1.000293 and nwater = 1.330. Snell's Law then yields the fact that light rays bend toward the normal as they pass from air to water and do the opposite upon exiting. However, these values of the indices of refraction are for a specific wavelength of light (actually a standard color of yellow light emitted from excited atoms of sodium with a wavelength of 589.3 nm). The degree of refraction varies slightly across the visible wavelengths, leading to the separation of colors that we observe as a rainbow. The small droplets of water in the atmosphere are roughly spheres, leading to the kind of refraction illustrated below:

Note that the angles by which the light rays are refracted depends on where it hits the drop (the redness of the lines has no significance in this image) since the boundary between water and air is spherical, rather than flat. Each of the rays shown undergoes a single internal reflection before emerging from the water droplet, though some light just passes through, and some is internally reflected multiple times (more on this later). However, the maximum angle between the incoming and outgoing rays are different for different colors of light: in particular, they are greater for longer wavelengths than shorter. Therefore, at the very highest angles, the colors are separated.

At one end of the spectrum, violet light has a maximum angle of 40° from the incoming light ray, while in the longest visible wavelengths, red light has a maximum angle of 42° (left). As a result, for a fixed observer, red light will appear to come from a certain angle in the sky, while violet will appear to come from another (right). Orange, yellow, green, blue, and indigo will appear in between. The result is what we see as a rainbow.

Several properties of rainbows follow directly from this understanding. The first is that all (primary) rainbows are of the same angular size in the sky, namely 42° in radius. A rainbow therefore does not have a fixed position and appears the same size to every observer, meaning that every observer in fact sees their own rainbow. Also, the center of the rainbow's circular arc must be opposite to the position of the Sun in the sky. This point is called the anti-solar point and must always be below the horizon (since the Sun is above). As a result, the higher the Sun is in the sky, the lower the (primary rainbow). If the Sun is more than 42° above the horizon, it cannot be seen at all. This is why rainbows are typically seen early in the morning or later in the afternoon. In addition, though the maximum angle is 40-42° for different colors of light, some light (of all colors) is reflected from raindrops at smaller angles, making the sky just inside the rainbow noticeably brighter. This effect is apparent in the image above.

Though most light reflected within the raindrop undergoes only a single internal reflection, some is in fact reflected more than once, leading to what are known as higher-order rainbows, notably the secondary rainbow.

The colors of the secondary rainbow are reversed since an additional reflection inside the drop reverses the color spread. Further, it is situated at 52°, outside the primary rainbow, and is considerably fainter.

The secondary rainbow is sometimes too faint to be visible, but it is always there. In fact, light can reflect internally even more, producing higher-order rainbows. However, three reflections sends the light on a path at about 43° inclined from its original trajectory, meaning that it would form a circle of this radius around the Sun. Due to its faintness and proximity to the Sun, it is very difficult to photograph, but photographs have recently captured this phenomenon (see below).

Thus, a simple application of atmospheric optics may explain the rainbow, the beauty of which has captivated humanity since antiquity.

Sources: http://www.atoptics.co.uk/rainbows/primary.htm, http://www.physicsclassroom.com/class/refrn/Lesson-4/Rainbow-Formation, http://0.tqn.com/d/weather/1/S/j/T/-/-/water-drop-prism-lrg_nasascijinks.png, http://ephy.in/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/clip_image0061.png, http://www.nilvalls.com/supernumerary-rainbow/, http://www.atoptics.co.uk/rainbows/ord34.htm

Labels:

Meteorology

Wednesday, April 15, 2015

Annular Tropical Cyclones

An annular tropical cyclone is a tropical cyclone (various types of which are hurricane, typhoon, tropical storm, or simply cyclone, depending on location and intensity) with certain distinguishing structural characteristics. These characteristics not only affect the appearance of the tropical cyclone but also its evolution and interaction with the surrounding environment.

The word "annular", meaning "ring-shaped", describes the shape of this type of system. The image below demonstrates the visual differences between ordinary and annular tropical cyclones.

The top image shows a "normal" tropical cyclone, Hurricane Igor of 2010. The bottom image is Hurricane Isabel of 2003, during an annular stage. Though the cyclones were of comparable intensities, they differ greatly in structure. A typical powerful tropical cyclone will have a relatively small eye and spiral rain bands emanating far from the center of circulation. Annular tropical cyclones, on the other hand, have large, symmetric eye features, and are almost perfectly circular. In addition, they tend to be smaller and more compact than other cyclones (the images above are not to the same scale).

Annular tropical cyclones were not recognized as a distinct category until 2002, at which time the concept was introduced in a paper (see here). This idea was created in an effort to explain a class of cyclones which not had a different appearance but also had a notorious tendency to defy prediction, especially intensity forecasting.

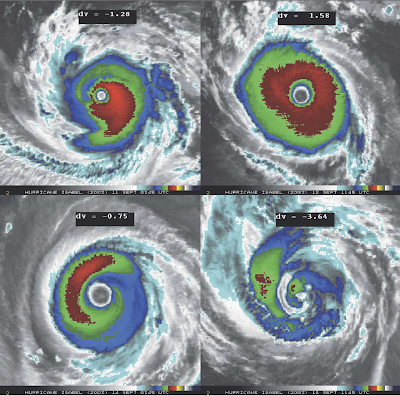

In an effort to objectively define whether a given tropical cyclone is annular, researchers developed an algorithm to measure the characteristics of annular tropical cyclones. Using satellite data to measure cloud heights, eye radii, and the like, the algorithm takes a satellite image of a cyclone and outputs a numerical value: the annular hurricane index. If this value is less than zero, the cyclone is non-annular, but if the value is greater than zero, it is annular.

Since the algorithmic method derives a numerical value from a still satellite image, it follows that the index may change with time, and thus that a single tropical cyclone may at one time be annular and at other times not. This reflects observational intuition: weak cyclones by their very nature do not have the symmetry and eye structures which factor into the annular hurricane index. Being annular is a phase of a tropical cyclone's evolution, not an inherent property of a cyclone, and cyclones can further be annular at different intensities and for different durations.

The above image appears in the paper introducing the annular hurricane index (see here for the source). It shows several stages of evolution of a single hurricane, once again Hurricane Isabel of 2003. The different colors on the infrared images indicate various cloud top temperatures. The cooler a cloud top, the higher its altitude, and (roughly) the stronger the storm at that location. In the first image (from September 11), the strengthening category 4 Isabel still possesses visible banding features to the south and east and is notably asymmetric, resulting in a negative annular hurricane index. By the second image on September 12, Isabel was a category 5 hurricane, had lost all bands, and was close to circular in structure. With an index of 1.58, the cyclone met the criteria of an annular cyclone on this date. The third image, taken September 14, shows the hurricane, still a category 5, with quite circular cloud coverage and still little banding. However, the distribution of the coldest cloud tops is asymmetric, resulting in a slightly negative index for this date. By September 18, the hurricane had weakened to a category 2, and some dry air had invaded the system. The spiral structure contributed to the index being far below zero for this date.

Annular tropical cyclones also intensify and weaken quite differently from typical cyclones. While on intensifying trends, typical hurricanes and typhoons will often fluctuate in intensity once they reach major hurricane wind speeds (111 mph and up). The cause of this phenomenon is called the eyewall replacement cycle.

An eyewall replacement cycle is a process during which the eyewall (the ring of strong thunderstorms surrounding the eye) of a cyclone contracts, dissipates, and is replaced by another. The image above, from the Hurricane Research Division of the NOAA, illustrates such a cycle in the evolution of Hurricane Wilma, the most intense Atlantic hurricane ever recorded. The top row shows a series of visible satellite pictures, the second row infrared images, and the bottom vertical cross-sections through the center of the hurricane, showing approximate cloud heights.

The first column illustrates Wilma's compact eye at the time of its record peak intensity on October 19. In the second column, taken October 20, a new ring of clouds, the secondary eyewall, has completely surrounded the first. When this occurs, the first eyewall loses access to moisture and weakens, causing the eye to visibly cloud over just as it does in the second column. With a less-defined center of circulation, the maximum winds decrease and the pressure rises (in this case, Wilma weakened from a category 5 to a category 4). By the third image (from October 21) the first eyewall has dissipated completely, and the secondary wall has become the new primary one, causing the intensity of Wilma to level out (at least temporarily).

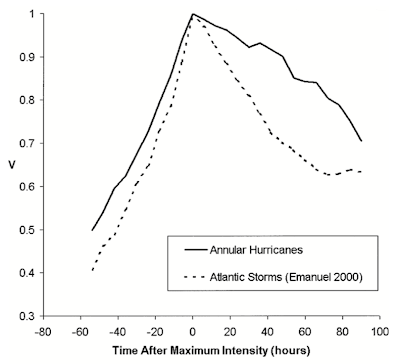

However, annular cyclones generally do not experience eyewall replacement cycles, instead maintaining their characteristic large, circular eyes for days at a time. This property exemplifies a more general trend: annular cyclones respond less to changes in their environment than regular tropical cyclones. In particular, having reached their peak intensity, they, in the absence of very cold water or land interaction, tend to weaken only very slowly.

The above graph compares annular hurricanes (6 cases) and other Atlantic hurricanes (56 cases) that did not encounter especially hostile conditions (again, land and very cold water). The intensity trends of the cyclones were averaged and normalized, so that a v-value of 1 corresponds to the peak intensity of a cyclone. Notably, annular hurricanes strengthen slightly more slowly and weaken significantly more slowly than their ordinary counterparts. Examples include 2014's Hurricane Iselle in the Pacific, which maintained hurricane intensity over marginal sea surface temperatures much longer than expected by forecasters. Iselle ultimately made landfall in Hawaii as a tropical storm, a very rare occurrence.

Annular cyclones form a very distinct class of cyclones that exhibit abnormal behavior. Though we do not yet fully understand how and why these cyclones form and act as they do, we continue to make advances in their identification and prediction, including the development of the annular hurricane index. Further research will help us comprehend these cyclones and more adequately prepare for them.

Sources: http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/2007WAF2007031.1, http://rammb.cira.colostate.edu/resources/docs/annular_Knaff.pdf, http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=45780, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annular_tropical_cyclone, http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2014/ep09/ep092014.discus.013.shtml?, http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/D8.html

The word "annular", meaning "ring-shaped", describes the shape of this type of system. The image below demonstrates the visual differences between ordinary and annular tropical cyclones.

The top image shows a "normal" tropical cyclone, Hurricane Igor of 2010. The bottom image is Hurricane Isabel of 2003, during an annular stage. Though the cyclones were of comparable intensities, they differ greatly in structure. A typical powerful tropical cyclone will have a relatively small eye and spiral rain bands emanating far from the center of circulation. Annular tropical cyclones, on the other hand, have large, symmetric eye features, and are almost perfectly circular. In addition, they tend to be smaller and more compact than other cyclones (the images above are not to the same scale).

Annular tropical cyclones were not recognized as a distinct category until 2002, at which time the concept was introduced in a paper (see here). This idea was created in an effort to explain a class of cyclones which not had a different appearance but also had a notorious tendency to defy prediction, especially intensity forecasting.

In an effort to objectively define whether a given tropical cyclone is annular, researchers developed an algorithm to measure the characteristics of annular tropical cyclones. Using satellite data to measure cloud heights, eye radii, and the like, the algorithm takes a satellite image of a cyclone and outputs a numerical value: the annular hurricane index. If this value is less than zero, the cyclone is non-annular, but if the value is greater than zero, it is annular.

Since the algorithmic method derives a numerical value from a still satellite image, it follows that the index may change with time, and thus that a single tropical cyclone may at one time be annular and at other times not. This reflects observational intuition: weak cyclones by their very nature do not have the symmetry and eye structures which factor into the annular hurricane index. Being annular is a phase of a tropical cyclone's evolution, not an inherent property of a cyclone, and cyclones can further be annular at different intensities and for different durations.

The above image appears in the paper introducing the annular hurricane index (see here for the source). It shows several stages of evolution of a single hurricane, once again Hurricane Isabel of 2003. The different colors on the infrared images indicate various cloud top temperatures. The cooler a cloud top, the higher its altitude, and (roughly) the stronger the storm at that location. In the first image (from September 11), the strengthening category 4 Isabel still possesses visible banding features to the south and east and is notably asymmetric, resulting in a negative annular hurricane index. By the second image on September 12, Isabel was a category 5 hurricane, had lost all bands, and was close to circular in structure. With an index of 1.58, the cyclone met the criteria of an annular cyclone on this date. The third image, taken September 14, shows the hurricane, still a category 5, with quite circular cloud coverage and still little banding. However, the distribution of the coldest cloud tops is asymmetric, resulting in a slightly negative index for this date. By September 18, the hurricane had weakened to a category 2, and some dry air had invaded the system. The spiral structure contributed to the index being far below zero for this date.

Annular tropical cyclones also intensify and weaken quite differently from typical cyclones. While on intensifying trends, typical hurricanes and typhoons will often fluctuate in intensity once they reach major hurricane wind speeds (111 mph and up). The cause of this phenomenon is called the eyewall replacement cycle.

An eyewall replacement cycle is a process during which the eyewall (the ring of strong thunderstorms surrounding the eye) of a cyclone contracts, dissipates, and is replaced by another. The image above, from the Hurricane Research Division of the NOAA, illustrates such a cycle in the evolution of Hurricane Wilma, the most intense Atlantic hurricane ever recorded. The top row shows a series of visible satellite pictures, the second row infrared images, and the bottom vertical cross-sections through the center of the hurricane, showing approximate cloud heights.

The first column illustrates Wilma's compact eye at the time of its record peak intensity on October 19. In the second column, taken October 20, a new ring of clouds, the secondary eyewall, has completely surrounded the first. When this occurs, the first eyewall loses access to moisture and weakens, causing the eye to visibly cloud over just as it does in the second column. With a less-defined center of circulation, the maximum winds decrease and the pressure rises (in this case, Wilma weakened from a category 5 to a category 4). By the third image (from October 21) the first eyewall has dissipated completely, and the secondary wall has become the new primary one, causing the intensity of Wilma to level out (at least temporarily).

However, annular cyclones generally do not experience eyewall replacement cycles, instead maintaining their characteristic large, circular eyes for days at a time. This property exemplifies a more general trend: annular cyclones respond less to changes in their environment than regular tropical cyclones. In particular, having reached their peak intensity, they, in the absence of very cold water or land interaction, tend to weaken only very slowly.

The above graph compares annular hurricanes (6 cases) and other Atlantic hurricanes (56 cases) that did not encounter especially hostile conditions (again, land and very cold water). The intensity trends of the cyclones were averaged and normalized, so that a v-value of 1 corresponds to the peak intensity of a cyclone. Notably, annular hurricanes strengthen slightly more slowly and weaken significantly more slowly than their ordinary counterparts. Examples include 2014's Hurricane Iselle in the Pacific, which maintained hurricane intensity over marginal sea surface temperatures much longer than expected by forecasters. Iselle ultimately made landfall in Hawaii as a tropical storm, a very rare occurrence.

Annular cyclones form a very distinct class of cyclones that exhibit abnormal behavior. Though we do not yet fully understand how and why these cyclones form and act as they do, we continue to make advances in their identification and prediction, including the development of the annular hurricane index. Further research will help us comprehend these cyclones and more adequately prepare for them.