This document provides a summary of noise programs implemented at airports located outside of the 65 DNL noise contour. It discusses common noise mitigation programs including land acquisition, sound insulation of homes, operational restrictions, and noise monitoring. The synthesis examines practices at 19 U.S. and Canadian airports to identify techniques that have helped address aircraft noise impacts in surrounding communities.

![6

CHAPTER TWO

REGULATIONS, POLICIES, AND COURT CASES GOVERNING

ISSUES OF NOISE OUTSIDE DNL 65

There are a number of existing and emerging reasons that air- impact. This block-rounding will double the number of

port operators may need or desire to take action to address homes eligible for insulation or purchase assurance from

noise outside the DNL 65 contour, including the following: just more than 1,000 to more than 2,000 (“ATA Says

Block-Rounding at Bob Hope, Ft. Lauderdale Int’l Has

• Because of complaints from areas outside DNL 65, air- Gone Too Far” 2008).

ports have identified reasonable and cost-effective pro- • The existing noise compatibility program has matured

grams to reduce noise impacts at lower noise levels; this and substantial complaints exist in areas outside the DNL

is especially true for operational noise abatement flight 65 contour: A recent study conducted by the FAA’s Cen-

procedures, such as Continuous Descent Arrivals (CDA) ter of Excellence for aviation noise and emissions

[The Continuous Descent Arrival, also referred to as the research, PARTNER (Partnership for AiR Transporta-

Continuous Descent Approach, has proven to be highly tion Noise and Emission Reduction), concluded that sig-

advantageous over conventional “dive-and-drive” arrival nificant complaints come from areas beyond DNL 65 (Li

and approach procedures. The environmental and eco- 2007). The staff at airports that respond to aircraft noise

nomic benefits of CDA were demonstrated in flight tests complaints finds that an increasing portion of their time

at Louisville International Airport in 2002 and 2004; is spent addressing concerns from residents outside the

there are significant reductions in noise (on the order of 6 DNL 65.

to 8 dB for each event) owing to reductions in thrust and • Federal policy is moving outside DNL 65: The Joint

a higher average altitude (Clarke 2006)], and Noise Planning and Development Office has determined that

Abatement Departure Profiles (NADPs) [FAA Advisory noise must be aggressively addressed to meet the capac-

Circular (AC) 91-53A, Noise Abatement Departure Pro- ity requirements of the Next Generation Air Transporta-

files (1993), identifies two departure profiles—the close- tion System (NextGen). Recently, the FAA has identified

in departure profile and the distant departure profile—to targets for noise reduction, including a near-term target

be used by air carrier operators. The AC outlines accept- to maintain its current 4% annual reduction in the num-

able criteria for speed, thrust settings, and airplane con- ber of people exposed to DNL 65 or greater, and com-

figurations used in connection with each NADP. These mensurate or greater reduction of the number of people

NADPs can then be combined with preferential runway exposed to DNL 55–65; as well as a long-term target,

use selections and flight path techniques to minimize, to first bringing DNL 65 primarily within airport boundary,

the greatest extent possible, the noise impacts], as well and later DNL 55 primarily within airport boundary

as some advanced navigation procedures such as (FAA 2008).

Required Navigation Procedures [Area Navigation • Airports are required by court order: Two recent cases

(RNAV) enables aircraft to fly on any desired flight path [Naples v. FAA (2005) and State of Minnesota et al. v.

within the coverage of ground- or space-based naviga- MAC (2007)] have determined that airports must address

tion aids, within the limits of the capability of the self- noise impacts beyond the current DNL 65 land use com-

contained systems, or a combination of both capabilities. patibility guidelines.

As such, RNAV aircraft have better access and flexi-

bility for point-to-point operations. RNP is RNAV with Review of the actions leading to adoption of DNL 65 land

the addition of an onboard performance monitoring and use compatibility guideline indicates that it was intended to be

alerting capability (FAA 2008)]. adjusted as industry needs changed (in particular, as technol-

• Airports have adopted local land use compatibility ogy improvements resulted in quieter aircraft). Federal noise

guidelines that apply to lower impact levels: Several policy has always recognized that land use compatibility deci-

jurisdictions have used DNL 60 dB in defining planning sions should be made at the local level. In addition, adoption

objectives or goals (Coffman Associates 2000). of the DNL 65 guideline in the 1970s reflected a compromise

• Airports have made commitments in support of airport between what was environmentally desirable and what was

capacity projects; for example, at Ft. Lauderdale, the economically and technologically feasible at the time.

FAA agreed in its Final Environmental Impact Statement

(EIS) on a runway extension to allow Broward County to This chapter addresses the existing and proposed applicable

follow neighborhood boundaries to mitigate for noise laws, policies, and regulations, plus relevant court decisions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-14-2048.jpg)

![8

consistent with human hearing [by reducing the contri- In addition to establishing these noise measurement tools,

bution of lower and very high frequencies to the total FAR Part 150 established a program for airports to develop

level) [14 C.F.R. Pt 150, App A § A150.3(a)]. (1) a “noise exposure map” or NEM that models existing and

• For purposes of evaluating noise exposure, the FAA future noise exposure and identifies the areas of incompatible

selected the Day–Night Average Sound Level (DNL), the land use, and (2) a “noise compatibility program” or NCP that

24-hour average sound level, in decibels, for the period identifies, examines, and recommends to the FAA alternative

from midnight to midnight, obtained after the addition means to mitigate and abate noise [49 U.S.C §§ 47503 (noise

of ten decibels to sound levels for the periods between exposure maps) and 47504 (noise compatibility programs);

midnight and 7 a.m., and between 10 p.m. and mid- 14 C.F.R. Pt. 150].

night, local time. The symbol for DNL is Ldn [14 C.F.R.

Pt 150, App A § A150.3(b)]. The NCP often is a principal component of an airport’s

• With respect to land use compatibility, the FAA pub- overall noise program since the NCP (1) is intended to be com-

lished a table in its regulations (14 C.F.R. Part 150, prehensive, both in its evaluation of noise issues and potential

Appendix A), which prescribes whether a variety of dif- solutions, (2) presents an opportunity for community involve-

ferent land use categories are compatible with aircraft ment and input, and (3) provides an indication of which noise

operations for a particular range of noise levels (14 control measures are eligible for federal funding.

C.F.R. Pt 150, App A § Table 1). That table identifies

DNL 65 dB as the threshold of compatibility for most Part 150 identifies certain measures that should be consid-

residential land uses, and where measures to achieve ered in preparing the noise compatibility program; these are

outdoor to indoor Noise Level Reduction of at least 25 summarized in Table 2.

dB and 30 dB should be incorporated into building

codes and be considered in individual approvals.

POLICIES ADDRESSING NOISE OUTSIDE DNL 65

Each of these requirements has been the subject of confu-

sion and contention. For example, there have been complaints Aircraft noise and land use compatibility has long been recog-

that dB(A) fails to account for low frequency noise (experi- nized as an important consideration in planning of communi-

enced as vibration or rumble) often associated with jet opera- ties and the airports that serve these communities (President’s

tions. The primary complaint with DNL is that it does not Airport Commission May 1952). The quantitative approach to

reflect the sound of individual aircraft operations, which may determining land uses compatible with aircraft noise began

be dramatically louder than the steady rate of sound captured with the Noise Control Act of 1972. It required the U.S. EPA

by DNL. In addition, although some contend that the DNL Administrator to conduct a study of the “ . . . implications of

65 dB level represents a scientifically and statistically accurate identifying and achieving levels of cumulative noise exposure

predictor of community annoyance, others assert that it is a around airports . . . ” (U.S. EPA 1973). This requirement

poor predictor of how a particular community or an individual resulted in the identification of DNL as the measure of cumu-

responds to aircraft noise. lative noise, and DNL 60 dB as the threshold of compatibility;

TABLE 2

NOISE COMPATIBILITY PROGRAM MEASURES

Operational Measures Land Use Measures Program Management Measures

• Implementing a preferential • Acquiring noise-impacted property • Posting signs on the airfield and at

runway system to direct air traffic • Acquiring “avigation easements” or other other locations at the airport to notify

over less-populated areas interests in property that permit aircraft to pilots about recommended flight pro-

• Using flight procedures, including fly over the property in exchange for pay- cedures and other measures

noise abatement approach and ments or other consideration • Creating a noise office at the airport

departure procedures • Requiring disclosure about the presence of and/or assigning responsibility for

• Identifying flight tracks to reduce the airport and potential noise impacts in noise issues to a staff member

noise and/or direct air traffic over real estate documents • Creating a dedicated telephone line or

less-populated areas • Constructing berms or other noise barriers other means for neighbors to submit

• Adopting mandatory restrictions • Sound insulation of structures used for comments/complaints about the air-

based on aircraft noise characteristics, noise-sensitive land uses (e.g., residences, port and individual aircraft operations

such as curfews schools, nursing homes) • Making flight track information avail-

• Identifying a particular area of the • Requiring the use of sound insulating able to the public

airport that can be used for aircraft building materials in new construction • Developing educational materials

engine runups and constructing a • Imposing zoning or other controls on noise- about the airport’s noise program for

“ground runup enclosure” to reduce sensitive land uses in impacted areas, pilots, other airport users, and commu-

noise from runups including prohibiting such development or nity members

requiring special permits and approvals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-16-2048.jpg)

![19

CHAPTER FIVE

LAND USE AND SOUND INSULATION POLICIES

This chapter summarizes land use policies that prevent or owners and realtors have no identified cost, airports noted

remediate incompatibilities outside of DNL 65, including other costs included city and county planning agencies and

review of development proposals, zoning, easements, disclo- administrative.

sure, sound insulation, building performance standards, and

property acquisition. Respondents indicated that the greatest challenges to

implementation are coordinating with local land use officials

(32%), coordinating with realtors (21%) and coordinating

PREVENTIVE LAND USE PLANNING with homeowners (18%). Respondents also noted “Not all

realtors or homeowners are cooperative even though they can

More than half of the surveyed airports (57%) reported having

be sued for non-compliance,” “Recommendations [are] not

land use compatibility measures that apply outside DNL 65.

always heeded,” and “Sometimes the local officials do not

The tools used by airports for land use compatibility planning

contact the airport on critical land development.”

include zoning, building permits that require sound insulation

of residential and noise-sensitive nonresidential land uses, and

Respondents reported a range of effectiveness: 21% said

disclosure to residents. Two airports reported that zoning pro-

their efforts were “very effective” in preventing incompatible

hibits residential development from DNL 60 to 65, and two

land uses outside DNL 65, 64% said their efforts were “some-

airports permit residential development with sound insulation

what or moderately effective,” and 16% said their efforts were

provided at either DNL 55 or 60. Other land use strategies

“not effective at all” (Figure 9).

include noise overlay districts, state compatibility plans, air-

port influence areas, and disclosure to 1 mile outside DNL 60.

Navigation easements are used by 75% of the responding air- SOUND INSULATION

ports. Real estate disclosures are used by 65% of the respond-

ing airports. The majority of respondents (58%) do not provide sound insu-

lation to homeowners living outside DNL 65; 20% provide

Land use compatibility policies are communicated to sound insulation for homes in contiguous neighborhoods

homeowners and realtors through newsletters or handouts (“block rounding”), and an additional 15% provide sound insu-

(27%), presentation to real estate boards (32%), and individ- lation for homes within the DNL 60 dB contour. Funding for

ual homeowner briefings (12%); 17% used other means of sound insulation programs outside DNL 65 comes from the air-

communication, such as working with government planning port (50%), FAA funding through Passenger Facility Charges

departments, public meetings, and responding to complaints. or AIP grants (36%), operators (7%), and homeowners (7%).

The airports’ cost to implement land use incompatible poli- Costs per home were reported between $10,000 and $15,000.

cies outside DNL 65 are minimal: five respondents reported Airports use a combination of funding sources for a maximum

that their costs are “minimal” or that they rely on in-house cost of $3.1 million for the entire program and a minimum

construction, legal, and staff time; one respondent identified cost of $10,000 per home. The FAA contributed 80% funding

total implementation costs of $250,000. Although home- for contiguous neighborhood sound insulation programs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-27-2048.jpg)

![29

REFERENCES

“Airport Input Sought for ACRP Study of Noise Programs FAA Order 1050.1E, change 1, “Environmental Impacts:

Going Outside DNL 65,” Airport Noise Report, Vol. 20, Policies and Procedures,” Mar. 20, 2006.

p. 46. FAA Order 5050.4B, National Environmental Policy Act

“Airport Noise Compatibility Planning,” 14 CFR Part 150, (NEPA) Implementing Instructions for Airport Actions,

Federal Aviation Administration, Washington, D.C., 1981. Apr. 28, 2006, replaces FAA Order 5050.4A, Airport

“ATA Says Block-Rounding at Bob Hope, Ft. Lauderdale Int’l Environmental Handbook, Great Lakes Region Planning/

Has Gone Too Far,” Airport Noise Report, Vol. 20, p. 78. Programming Branch, FAA Airports Division, Washing-

Berkeley Keep Jets over the Bay Committee v. Board of Port ton, D.C.

Commissioners of Oakland, Nos. A086708, A087959, FAA Order 5100.38C, Airport Improvement Program Hand-

A089660, Court of Appeal, First District, Division 2, Cal- book, Chapter 7, Section 706, “Land Acquisition for Noise

ifornia, Aug. 30, 2001. Compatibility,” and Chapter 8, “Noise Compatibility Proj-

C.A.R.E. Now, Inc. v. F.A.A., 844 F.2d 1569 (11th Cir. 1988). ects,” June 28, 2005, Washington, D.C.

Citizens Against Burlington, Inc. v. Busey, 938 F.2d 190 (D.C. FAA RNAV/RNP Group website [Online]. Available: http://

Cir. 1991). www.faa.gov/ato?k=pbn [accessed Nov. 3, 2008].

City of Bridgeton v. Slater, 212 F.3d 448 (8th Cir. 2000). Li, K., G. Eiff, J. Laffitte, and D. McDaniel, Land Use Man-

City of Naples Airport Authority, Petitioner v. Federal Avi- agement and Airport Controls: Trends and Indicators of

ation Administration, Respondent, 409 F.3d 431 (D.C. Incompatible Land Use, Report No. PARTNER-COE-

Cir. 2005). 2008-001, Dec. 2007.

Clarke, J.-P., et al., Development, Design, and Flight Test Los Angeles World Airports, LAX Master Plan website,

Evaluation of a Continuous Descent Approach Procedure Community Benefits [Online]. Available: http://www.lax

for Nighttime Operation at Louisville International Air- masterplan.org/comBenefits.cfm [accessed Nov. 3, 2008].

port, Report No. PARTNER-COE-2005-02, Jan. 9, 2006. Maryland Department of Aviation, State Aviation Adminis-

Coffman Associates, Lincoln NE, Airport Part 150, Appendix tration, Selection of Airport Noise Analysis Method and

E, Support Documentation for Land Use Regulations Exposure Limits, Baltimore, Jan. 1975.

within and below DNL 65, Table A, 2000. Morongo Band of Mission Indians v. FAA, 161 F.3d 569 (9th

Communities, Inc. v. Busey, 956 F.2d 619 (6th Cir. 1992). Cir. 1998).

Department of Defense, Air Installations Compatible Use President’s Airport Commission, The Airport and Its Neigh-

Zones, Number 4165.57, Washington, D.C., Nov. 8, 1977 bors: The Report of the President’s Airport Commission,

[Online]. Available: http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/ May 1952.

corres/text/i416557p.txt. Public Law 108-176, H.R.2115, Vision 100—Century of Avi-

Department of Defense, Joint Land Use Study (JLUS), Pro- ation Reauthorization Act, Dec. 2003.

gram Guidance Manual, Washington, D.C., Aug. 2002. Seattle Comm. Council Fed’n v. FAA, 961 F.2d 829 (9th Cir.

Department of Transportation, Aviation Noise Abatement 1992).

Policy, Washington, D.C., Nov. 18, 1976. State of Minnesota et al. v. Metropolitan Airports Commission

FAA, Noise Abatement Departure Profile, Advisory Circular, (MAC) and Northwest Airlines (Cities Litigation) Case

AC 91-53A, Washington, D.C., July 22, 1993. No. 277-CV-05-5474, District Court, County of Hen-

FAA, AIP, and PFC Funding Summary for Noise Compati- nepin, Nov. 2007.

bility Projects [Online]. Available: http://www.faa.gov/ Suburban O’Hare Comm’n v. Dole, 787 F.2d 186 (7th Cir.

airports_airtraffic/airports/environmental/airport_noise/ 1986), cert. denied 479 U.S. 847.

part_150/funding/ [accessed Nov. 3, 2008]. U.S. EPA, Impact Characterization of Noise Including Impli-

FAA, Great Lakes Region, Final Record of Decision, cations of Identifying and Achieving Levels of Cumulative

Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport, Dual Track Noise Exposure, PB224408, Environmental Protection

Airport Planning Process: New Runway 17/35 and Air- Agency, Washington, D.C., July 1973.

port Layout Plan Approval, Minneapolis, Sep. 1998. U.S. EPA, Information on Levels of Environmental Noise

FAA, NextGen Environmental Goals and Targets, ACI-NA Requisite to Protect Public Health and Welfare with an

Environmental Committee, Sep. 21, 2008, Lynne Pickard, Adequate Margin of Safety, Environmental Protection

Deputy Director FAA Office of Environment & Energy Agency, Washington, D.C., Mar. 1974.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-37-2048.jpg)

![94

APPENDIX C

Case Study: Dallas/Ft. Worth International Airport

AIRPORT BACKGROUND meet its FAA Grant Assurances obligation to protect lands in

the airport environs from incompatible development. DFW is

Dallas/Ft. Worth International Airport (DFW) first opened to currently under pressure from local municipalities to update its

traffic on January 13, 1974. It is jointly owned by the cities of policy contours to reflect actual (current) noise conditions, and

Dallas and Fort Worth and is operated by the DFW Airport has committed good faith efforts to provide this noise con-

Board. DFW covers more than 29.8 square mile (18,076 acres), tour update by January 2009. An important question remains

and now has seven runways (Figure C1) (Much of the infor- whether local jurisdictions will adopt updated noise contours

mation in this case study came directly from DFW’s Noise for land use planning purposes, which will no doubt result in

Compatibility Office, specifically its memorandum entitled noise-sensitive development closer to DFW.

“Mission Relevance,” February 18, 2008.) DFW had 685,491

operations in 2007, making it the third busiest airport in the

world based on operations; with 59,786,476 passengers in OPERATIONAL MEASURES

2007, it was also the seventh busiest based on passengers

DFW has two operational noise abatement measures: (1) a

[“Facts about DFW” http://www.dfwairport.com/visitor/index.

Preferential Runway Use Plan, and (2) Area Navigation Flight

php?ctnid=24254 (accessed Sep. 8, 2008)].

Procedures (RNAV).

Aircraft noise was not a serious community issue prior to

The DFW Runway Use Plan was developed following the

the launch of DFW’s Airport Development Plan in 1987. In

1992 Final EIS for two proposed runways and other capacity

1990, an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the build-

improvements (FEIS Section 4.5.1.1 and ROD Chapter 4).

ing of two new runways and redevelopment of terminals was

The Preferential Runway Use System identified in that plan

released. Neighboring cities challenged DFW Airport on zon-

“provides a hierarchical rating of runway use for arrivals and

ing authority; court tests ensued on the EIS. In 1992, the FAA

departures by aircraft type.” This system is used under typical

issued a favorable Record of Decision (ROD), approving

operations conditions and during typical operating hours; addi-

Runways 16/34 East and West. Three cities filed suit to chal-

tional stipulations are applied during late night hours (10 p.m.

lenge DFW’s expansion in state and federal courts. In 1993,

to 7 a.m.) (Runway Use Plan 1996). The preferential runway

the Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 348 reaffirming that

use plan for turbojet aircraft is shown in Table C1.

DFW is exempt from local zoning ordinances; the U.S. Court

of Appeals ruled in favor of DFW on the EIS lawsuit, and

At DFW, the FAA has replaced conventional departure

DFW held the ground breaking for Runway 16/34 East. The

procedures, which rely on controller instructions and vector-

ROD on the 1992 Final EIS tasked the Airport to “implement

ing, with RNAV departure procedures. RNAV relies on pre-

an extensive noise mitigation program . . . to mitigate for the

programmed routing and satellite navigation. Deployment of

increased noise levels to residences and other noise-sensitive

RNAV at DFW contributed to FAA’s nationwide implemen-

uses.” In particular, the ROD required DFW to establish a

tation strategy to develop more precise and efficient arrival

noise and flight track monitoring system to assure communi-

and departure procedures at U.S. airports enhancing airspace

ties that noise would not exceed predicted levels.

efficiency and safety, reducing air emissions, and reducing

delays. DFW was one of the first airports in the nation to use

NOISE COMPATIBILITY PROGRAM this departure technology.

DFW has never conducted a formal Part 150 study; neverthe- According to the Air Transport Association, RNAV tech-

less, DFW has a comprehensive noise abatement program, nology increases the number of aircraft departures handled at

which includes operational procedures [most notably prefer- DFW by approximately 14%. RNAV Departure Procedures

ential runway use program and RNAV (area navigation) pro- can be accommodated generally within existing flight corri-

cedures], land use measures (preventive land use planning as dors and using existing approved headings. The use of RNAV

well as mitigation for limited areas), and outreach (a state-of- reduces the overall number of population over-flown. RNAV

the-art noise and flight track monitoring system, and public departure corridors are compressed, which concentrates

outreach facilities). large volumes of aircraft activity over relatively small areas.

RNAV effects on DFW’s departure patterns are illustrated

Arguably, the most important element of DFW’s noise pro- in Figure C2. Ninety-five percent of DFW’s turbojet fleet

gram is the adoption of “noise policy contours” and diligence was equipped to fly the RNAV procedures by 2007. The

on the part of DFW Noise Compatibility Office (NCO) staff to FAA estimates an $8.5 million annual savings with the new](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-102-2048.jpg)

![97

FIGURE C4 Southlake land use proposals acted on by the DFW Noise Compatibility Office.

agement designated the NCO the community liaison to restore ested audiences, large and small. This graphic capabil-

trust and reestablish credibility. The following tools are respon- ity has proven, over time, to be a premier tool in further-

sive to this declared responsibility: ing community and stakeholder education, outreach,

demonstrating transparency, and restoring credibility in

• DFW instituted several community forums and out- the context of DFW meeting its Final EIS noise-related

reach programs pursuant to the above referenced legis- mandates.

lation and responsive to the provisions embodied in the • DFW NCO staff often use noise and flight track data

1992 Final EIS. to inform communities about proposed modifications in

• DFW’s Noise Center (Figure C5) was established with flight track corridors and application of new technology

aircraft noise and flight track displays. This NCO func- [e.g., RNAV].

tion provides “real time” data presentations to inter- • DFW NCO tracks and responds to its Noise Complaint

Hotline; since 1999, noise complaints have dropped an

average of 20% per year (Figure C6).

• DFW has developed a number of informational brochures

and reports, including: Runway Use Plan, Noise Mon-

itoring Brochure(s), and related informational take-

away(s).

SUMMARY OF PROGRAM MEASURES

OUTSIDE DNL 65

The most recent DNL contours for DFW were prepared in

2002 for the Environmental Assessment of RNAV proce-

dures. Those contours show that the 65 DNL noise contour of

2002 is almost entirely within the airport property boundary.

Figure C7 presents a comparison of DNL 65 contours at DFW

FIGURE C5 DFW Noise Compatibility Center. over time, including: NCTCOG contours prepared in 1971](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-105-2048.jpg)

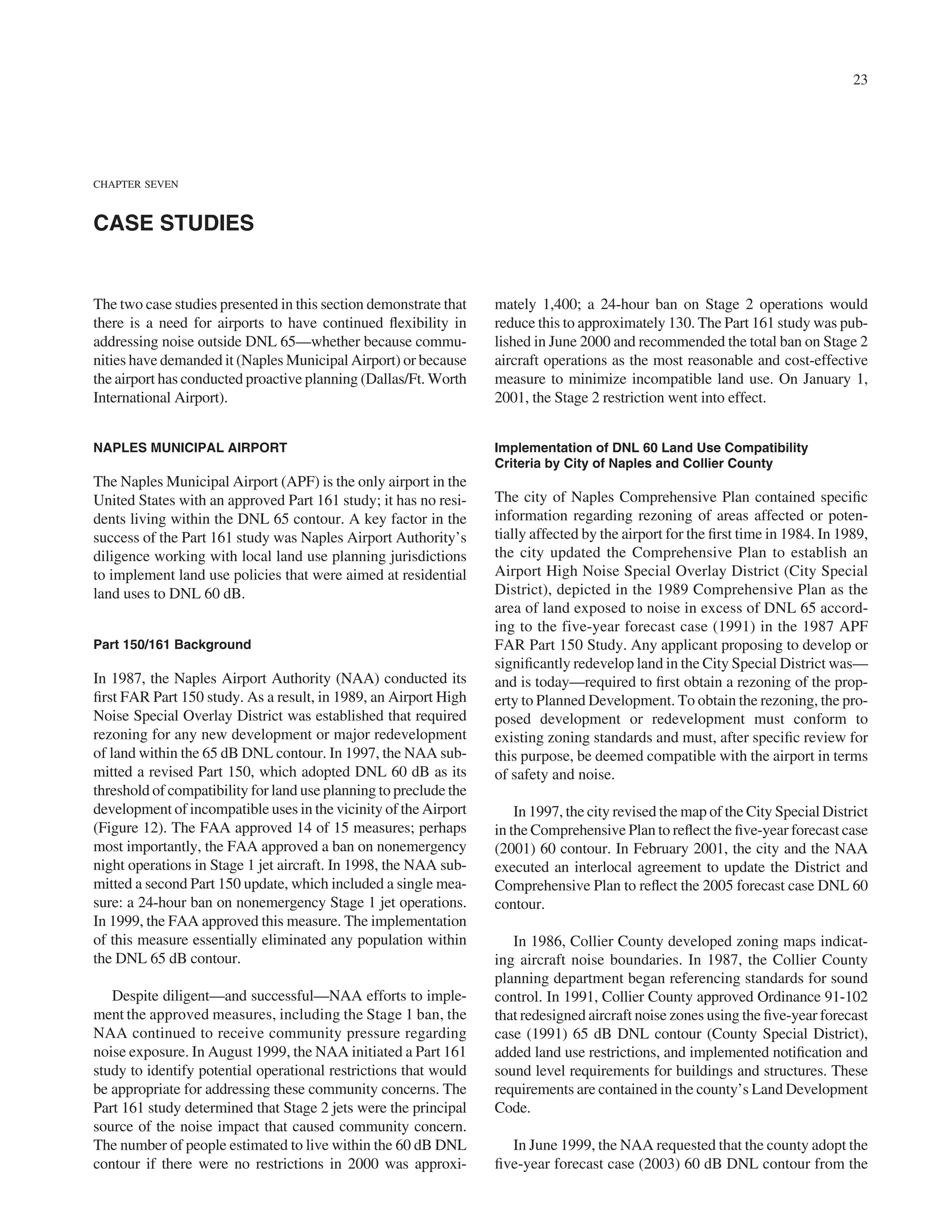

![102

TABLE D1

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS LEADING TO IMPLEMENTATION OF STAGE 2 RESTRICTION

Date Event Comments

June 23, 2000 NAA invitation to public to comment on

proposed restriction on Stage 2 jet operations at

Naples Municipal Airport

June 30, 2000 Part 161 study published Notice of study availability and

opportunity for comments distributed

widely

Nov. 16, 2000 Response to Comments published Responses provided for 36 comment

categories

Dec. 2000 FAA initiates enforcement action alleging NAA suspends enforcement of ban while

Stage 2 ban violated Part 161 responding to FAA.

Dec. 2000 National Business Aviation Association Ban upheld in federal district court,

(NBAA) and General Aviation Manufacturers September 2001.

Association (GAMA) sue NAA in federal court

alleging the ban is unconstitutional

Jan. 18, 2001 NAA meeting w/FAA staff Discuss FAA comments. FAA staff offer to

work with the NAA in an informal process

to resolve any agency concerns, approach

to supplemental analysis.

Aug. 2001 Part 161 Supplemental Analysis published

Oct. 2001 FAA found that the study fully complied with

the requirements of Part 161

Oct. 2001 FAA initiates second enforcement action under FAA alleges that Stage 2 ban violates the

Part 16 rules which require (1) Investigation, grant assurance that “the airport will be

(2) Hearing, and (3) Final Decision. available for public use on reasonable

conditions and without unjust

discrimination.”

March 2002 NAA enforces ban Grant money withheld

March 2003 INVESTIGATION: NAA appeals decision, provides responses

FAA issues 94-page “Director’s to all FAA allegations

Determination” that Stage 2 ban is preempted

by federal law and violated Grant Assurance

22—“make airport available for public use on

reasonable terms and without unjust

discrimination to all types, kinds, and classes of

aeronautical activities.”

June 2003 HEARING: Hearing Officer issues 56-page “Initial

FAA attorney appointed as Hearing Officer and Decision” that ban not preempted, not

conducts hearing on NAA appeal. unjustly discriminatory, but was (1)

unreasonable, (2) Part 161 compliance does

not affect Grant Assurance obligations, and

(3) FAA not bound by prior federal court

decision [see Dec. 2000, above]

July 2003 Both NAA and FAA appeal the Initial Decision

Aug. 2003 FINAL DECISION: Decision:

Associate Administrator issues Final Agency (1) FAA is not bound by prior federal court

Decision and Order—Grant funding to be decision because FAA was not a party to

withheld so long as NAA enforces Stage 2 ban. the case.

2) Compliance with Part 161 has no effect

on Grant Assurance Obligations.

3) Stage 2 ban unreasonable because there

is no incompatible land use problem in

Naples that warrants a restriction on airport

operations [because there is no

incompatible land use inside 65 dB DNL].

Sept. 2003 Naples Airport Authority files petition for Petition to U.S. Court of Appeals for the

review District of Columbia.

June 2005 U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Circuit Court found that it is permissible

Columbia Circuit rules Stage 2 ban is for NAA to consider the benefits of the

reasonable (and Grant Assurances not affected) restriction to noise-sensitive areas within

60 dB DNL.

It also found that Grant Assurances do

apply, but that because the ban is not

unreasonable, the Grants are not affected.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/compilationofnoiseprogramsinareasoutsidednl65-101222132731-phpapp02/75/Compilation-of-noise-programs-in-areas-outside-dnl-65-110-2048.jpg)