Digital Image Processing Using Matlab 2nd Edition Rafael C Gonzalez

- 1. Digital Image Processing Using Matlab 2nd Edition Rafael C Gonzalez download https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-image-processing-using- matlab-2nd-edition-rafael-c-gonzalez-4072380 Explore and download more ebooks at ebookbell.com

- 2. Here are some recommended products that we believe you will be interested in. You can click the link to download. Digital Image Processing Using Matlab 4th Edition Rafael C Gonzalez https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-image-processing-using- matlab-4th-edition-rafael-c-gonzalez-34385212 Digital Image Processing Using Matlab Rafael C Gonzalez Richard Ewoods https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-image-processing-using-matlab- rafael-c-gonzalez-richard-ewoods-50195688 Digital Image Processing Using Matlab 2nd Edition Rafael C Gonzalez https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-image-processing-using- matlab-2nd-edition-rafael-c-gonzalez-10945078 Digital Image Processing Using Matlab R Illustrated Edition Rafael C Gonzalez https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-image-processing-using-matlab-r- illustrated-edition-rafael-c-gonzalez-1273030

- 3. Digital Signal And Image Processing Using Matlab Volume 1 Fundamentals 2nd Edition Grard Blanchet https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-signal-and-image-processing- using-matlab-volume-1-fundamentals-2nd-edition-grard-blanchet-4969892 Digital Signal And Image Processing Using Matlab Volume 2 Advances And Applications The Deterministic Case 2nd Edition Grard Blanchet https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-signal-and-image-processing- using-matlab-volume-2-advances-and-applications-the-deterministic- case-2nd-edition-grard-blanchet-4978470 Digital Signal And Image Processing Using Matlab Grard Blanchet https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-signal-and-image-processing- using-matlab-grard-blanchet-50195680 Digital Signal And Image Processing Using Matlab Volume 3 Advances And Applications The Stochastic Case 2nd Edition Blanchet https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-signal-and-image-processing- using-matlab-volume-3-advances-and-applications-the-stochastic- case-2nd-edition-blanchet-5310236 Digital Image Processing Using Scilab 1st Ed Rohit M Thanki https://ebookbell.com/product/digital-image-processing-using- scilab-1st-ed-rohit-m-thanki-7150522

- 6. Second Edition Rafael C. Gonzalez University of Tennessee Richard E. Woods MedData Interactive Steven L. Eddins The MathWorks, Inc. Gatesmark Publishing @ A Division of Gatesmark.@ LLC www.gatesmark.com

- 7. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on File Library of Congress Control Number: 2009902793 Gatesmark Publishing A Division of Gatesmark , LLC www.gatesmark .com © 2009 by Gatesmark. LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without written permission from the publisher. Gatesmark Publishing'" is a registered trademark of Gatesmark. LLC www.gatcsmark.com. Gatesmarkc" is a registered trademark of Gatesmark. LLC. www.gatesmark.com. MATLAB"> is a registered trademark of The MathWorks. Inc.. 3 Apple Hill Drive, Natick, MA 01760-2098 The authors and publisher of this book have used their best efforts in preparing this book. These efforts include the development. research. and testing of the theories and programs to determine their effectiveness. The authors and publisher shall not he liable in any event for incidental or consequential damages with. or arising out of. the furnishing. performance. or use of these programs. Printed in the United Stall.!s of America IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 ISBN 978-0-9820854-0-0

- 8. To Ryan To Janice, David, andJonathan and To Geri, Christopher, and Nicholas

- 10. Contents Preface. xi Acknowledgements xiii About the Authors xv l Introduction 1 Previr?w 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 What Is Digital Image Processing? 2 1.3 Background on MATLAB and the Image Processing Toolbox 4 1.4 Areas of Image Processing Covered in the Book 5 1.5 The Book Web Site 7 1.6 Notation 7 1.7 TheMATLAB Desktop 7 1.7.l Using the MATLAB Editor/Debugger 10 1.7.2 Getting Help 10 1.7.3 Saving and Retrieving Work Session Data 11 1.8 How References Are Organized in the Book 11 Summary 12 2 Fundamentals 13 Preview 13 2.1 Digital Image Representation 13 2.1.l Coordinate Conventions 14 2.1.2 Images as Matrices 15 2.2 Reading Images 15 2.3 Displaying Images 18 2.4 Writing Images 21 2.5 Classes 26 2.6 Image Types 27 2.6.1 Gray-scale Images 27 2.6.2 Binary Images 27 2.6.3 A Note on Terminology 28 2.7 Converting between Classes 28 2.8 Array Indexing 33 2.8.l Indexing Vectors 33 2.8.2 Indexing Matrices 35 2.8.3 Indexing with a Single Colon 37 2.8.4 Logical Indexing 38 2.8.5 Linear Indexing 39 2.8.6 Selecting Array Dimensions 42 v

- 11. Vl • Contents 2.8.7 Sparse Matrices 42 2.9 Some Important Standard Arrays 43 2.10 Introduction to M-Function Programming 44 2.10.1 M-Files 44 2.10.2 Operators 46 2.10.3 FlowControl 57 2.10.4 Function Handles 63 2.10.5 Code Optimization 65 2.10.6 Interactive 1/0 71 2.10.7 An Introduction to Cell Arrays and Structures 74 Summary 79 3 Intensity Transformations and Spatial Filtering 80 Preview 80 3.1 Background 80 3.2 Intensity Transformation Functions 81 3.2.1 Functions imadj ust and stretchlim 82 3.2.2 Logarithmic and Contrast-Stretching Transformations 84 3.2.3 Specifying Arbitrary Intensity Transformations 86 3.2.4 Some Utility M-functions for Intensity Transformations 87 3.3 Histogram Processing and Function Plotting 93 3.3.1 Generating and Plotting Image Histograms 94 3.3.2 Histogram Equalization 99 3.3.3 Histogram Matching (Specification) 102 3.3.4 Function adapthisteq 107 3.4 Spatial Filtering 109 3.4.1 Linear Spatial Filtering 109 3.4.2 Nonlinear Spatial Filtering 117 3.5 ImageProcessing Toolbox Standard Spatial Filters 120 3.5.1 Linear Spatial Filters 120 3.5.2 Nonlinear Spatial Filters 124 3.6 Using Fuzzy Techniques for Intensity Transformations and Spatial Filtering 128 3.6.1 Background 128 3.6.2 Introduction to Fuzzy Sets 128 3.6.3 Using Fuzzy Sets 133 3.6.4 A Set of Custom Fuzzy M-functions 140 3.6.5 Using Fuzzy Sets for Intensity Transformations 155 3.6.6 Using Fuzzy Sets for Spatial Filtering 158 Summary 163 4 Filtering in the Frequency Domain 164 Preview 164

- 12. 4.1 The 2-D Discrete Fourier Transform 164 4.2 Computing and Visualizing the 2-D OFT in MATLAB 168 4.3 Filtering in the Frequency Domain 172 4.3.l Fundamentals 173 4.3.2 Basic Steps in DFT Filtering 178 4.3.3 An M-function for Filtering in the Frequency Domain 179 4.4 Obtaining Frequency Domain Filters from Spatial Filters 180 4.5 Generating Filters Directly in the Frequency Domain 185 4.5.1 Creating Meshgrid Arrays for Use in Implementing Filters in the Frequency Domain 186 4.5.2 Lowpass (Smoothing) Frequency Domain Filters 187 4.5.3 Wireframe and Surface Plotting 190 4.6 Highpass (Sharpening) Frequency Domain Filters 194 4.6.1 A Function for Highpass Filtering 194 4.6.2 High-Frequency Emphasis Filtering 197 4.7 Selective Filtering199 4.7.1 Bandreject and Bandpass Filters 199 4.7.2 Notchreject and Notchpass Filters 202 Summary 208 5 Image Restoration and Reconstruction 209 Preview 209 5.1 AModel of the Image Degradation/Restoration Process 210 5.2 Noise Models 211 5.2.l Adding Noise to Images with Function imnoise 211 5.2.2 Generating Spatial Random Noise with a Specified Distribution 212 5.2.3 Periodic Noise 220 5.2.4 Estimating Noise Parameters 224 5.3 Restoration in the Presence of Noise Only-Spatial Filtering 229 5.3.1 Spatial Noise Filters 229 5.3.2 Adaptive Spatial Filters 233 5.4 Periodic Noise Reduction Using Frequency Domain Filtering 236 5.5 Modeling the Degradation Function 237 5.6 Direct Inverse Filtering 240 5.7 Wiener Filtering 240 5.8 Constrained Least Squares (Regularized) Filtering 244 5.9 Iterative Nonlinear Restoration Using the Lucy-Richardson Algorithm 246 5.10 Blind Deconvolution 250 5.11 Image Reconstruction from Proj ections 251 5.11.l Background 252 5.11.2 Parallel-Beam Projections and the Radon Transform 254 5.11.3 The Fourier Slice Theorem and Filtered Backprojections 257 5.11.4 Filter Implementation 258 • Contents vii

- 13. viii • Contents 5.11.5 Reconstruction Using Fan-Beam Filtered Backprojections 259 5.11.6 Function radon 260 5.11.7 Function iradon 263 5.11.8 Working with Fan-Beam Data 268 Summary 277 6 Geometric Transformations and Image Registration 278 Preview 278 6.1 Transforming Points 278 6.2 Affine Transformations 283 6.3 Projective Transform ations 287 6.4 Applying Geometric Transform ations to Images 288 6.5 Image Coordinate Systems in MATLAB 291 6.5.1 Output Image Location 293 6.5.2 Controlling the Output Grid 297 6.6 Image Interpolation 299 6.6.1 Interpolation in Two Dimensions 302 6.6.2 Comparing Interpolation Methods 302 6.7 Image Registration 305 6.7.1 Registration Process 306 6.7.2 Manual FeatureSelection and Matching Using cpselect 306 6.7.3 Inferring Transformation Parameters Using cp2tform 307 6.7.4 Visualizing Aligned Images 307 6.7.5 Area-Based Registration 311 6.7.5 Automatic Feature-Based Registration 316 Summary 317 7 Color Image Processing 318 Preview 318 7.1 Color Image Representation in MATLAB 318 7.1.1 RGB Images 318 7.1.2 Indexed Images 321 7.1.3 Functions for Manipulating RGB and Indexed Images 323 7.2 Converting Between Color Spaces 328 7.2.l NTSC Color Space 328 7.2.2 The YCbCr Color Space 329 7.2.3 The HSY Color Space 329 7.2.4 The CMY and CMYK Color Spaces 330 7.2.5 The HSI Color Space 331 7.2.6 Device-Independent Color Spaces 340 7.3 T he Basics of Color Image Processing 349 7.4 Color Transformations 350 7.5 Spatial Filtering of Color Images 360

- 14. 7.5.1 Color Image Smoothing 360 7.5.2 Color Image Sharpening 365 7.6 Working Directly in RGBVector Space 366 7.6.1 Color Edge Detection Using the Gradient 366 7.6.2 Image Segmentation in RGB Vector Space 372 Summary 376 8 Wavelets 377 Preview 377 8.1 Background 377 8.2 The Fast Wavelet Transform 380 8.2.1 FWTs Using the Wavelet Toolbox 381 8.2.2 FWTs without the Wavelet Toolbox 387 8.3 Working with Wavelet Decomposition Structures 396 8.3.l Editing Wavelet Decomposition Coefficients without the Wavelet Toolbox 399 8.3.2 Displaying Wavelet Decomposition Coefficients 404 8.4 The Inverse Fast Wavelet Transform 408 8.5 Wavelets in Image Processing 414 Summary 419 9 Image Compression 420 Preview 420 9.1 Background 421 9.2 Coding Redundancy 424 9.2.1 Huffman Codes 427 9.2.2 Huffman Encoding 433 9.2.3 Huffman Decoding 439 9.3 Spatial Redundancy 446 9.4 Irrelevant Information 453 9.5 JPEG Compression 456 9.5.1 JPEG 456 9.5.2 JPEG 2000 464 9.6 Video Compression 472 9.6.1 MATLAB Image Sequences and Movies 473 9.6.2 Temporal Redundancy and Motion Compensation 476 Summary 485 l0 Morphological Image Processing 486 Preview 486 10.1 Preliminaries 487 10.1.1 Some Basic Concepts from Set Theory 487 10.1.2 BinaryImages, Sets, and Logical Operators 489 10.2 Dilation and Erosion 490 • Contents ix

- 15. X • Contents 10.2.1 Dilation 490 10.2.2 Structuring Element Decomposition 493 10.2.3 The st rel Function 494 10.2.4 Erosion 497 10.3 Combining Dilation and Erosion 500 10.3.1 Opening and Closing 500 10.3.2 The Hit-or-Miss Transformation 503 10.3.3 Using Lookup Tables 506 10.3.4 Function bwmorph 511 10.4 Labeling Connected Components 514 10.5 Morphological Reconstruction 518 10.5.1 Opening by Reconstruction 518 10.5.2 Filling Holes 520 10.5.3 Clearing Border Objects 521 10.6 Gray-Scale Morphology 521 10.6.l Dilation and Erosion 521 10.6.2 Opening and Closing 524 10.6.3 Reconstruction 530 Summary 534 11 Image Segmentation 535 Preview 535 11.1 Point, Line, and Edge Detection 536 11.1.1 Point Detection 536 11.1.2 Line Detection 538 11.1.3 Edge Detection Using Function edge 541 11.2 Line Detection Using the Hough Transform 549 11.2.1 Background 551 11.2.2 Toolbox Hough Functions 552 11.3 T hresholding 557 11.3.1 Foundation 557 11.3.2 Basic Global Thresholding 559 11.3.3 Optimum Global Thresholding Using Otsu's Method 561 11.3.4 Using Image Smoothing to Improve Global Thresholding 565 11.3.5 Using Edges to Improve Global Thresholding 567 11.3.6 Variable Thresholding Based on Local Statistics 571 11.3.7 Image Thresholding Using Moving Averages 575 11.4 Region-Based Segmentation 578 11.4.1 Basic Formulation 578 11.4.2 Region Growing 578 11.4.3 Region Splitting and Merging 582 11.5 Segmentation Using the Watershed Transform 588 11.5.1 Watershed Segmentation Using the Distance Transform 589 11.5.2 Watershed Segmentation Using Gradients 591 11.5.3 Marker-Controlled Watershed Segmentation 593

- 16. Summary 596 12 Representation and Description 597 Preview . 597 12.1 Background 597 12.1.1 Functions for Extracting Regions and Their Boundaries 598 12.1.2 Some Additional MATLAB and Toolbox Functions Used in This Chapter 603 12.1.3 Some Basic Utility M-Functions 604 12.2 Representation 606 12.2.l Chain Codes 606 12.2.2 Polygonal Approximations Using Minimum-Perimeter Polygons 610 12.2.3 Signatures 619 12.2.4 Boundary Segments 622 12.2.5 Skeletons 623 12.3 Boundary Descriptors 625 12.3.1 Some Simple Descriptors 625 12.3.2 Shape Numbers 626 12.3.3 Fourier Descriptors 627 12.3.4 Statistical Moments 632 12.3.5 Comers 633 12.4 Regional Descriptors 641 12.4.1 Function regionprops 642 12.4.2 Texture 644 12.4.3 Moment Invariants 656 12.5 Using Principal Components for Description 661 Summary 672 13 Object Recognition 674 Preview 674 13.1 Background 674 13.2 Computing Distance Measures in MATLAB 675 13.3 Recognition Based on Decision-Theoretic Methods 679 13.3.1 Forming Pattern Vectors 680 13.3.2 Pattern Matching Using Minimum-Distance Classifiers 680 13.3.3 Matching by Correlation 681 13.3.4 Optimum Statistical Classifiers 684 13.3.5 Adaptive Leaming Systems 691 13.4 Structural Recognition 691 13.4.1 Working with Strings in MATLAB 692 13.4.2 String Matching 701 Summary 706 xi

- 17. AppendixA Appendix 8 Appendix ( M-Function Summary 707 ICE and MATLAB Graphical User Interfaces 724 Additional Custom M-functions 750 Bibliography 813 Index 817

- 18. Preface This edition of Digital Image Processing Using MATLAB is a major revision of the book. As in the previous edition, the focus of the book is based on the fact that solutions to problems in the field of digital image processing generally require extensive experimental work involving software simulation and testing with large sets of sample images. Although algorithm development typically is based on theoretical underpinnings, the actual implementation of these algorithms almost always requires parameter estimation and, frequently, algorithm revision and comparison of candidate solutions. Thus, selection of a flexible, comprehen sive,and well-documented software development environment is a key factor that has important implications in the cost, development time, and portability of image processing solutions. Despite its importance, surprisingly little has been written on this aspect of the field in the form of textbook material dealing with both theoretical principles and software implementation of digital image processing concepts. The first edition of this book was written in 2004 to meet just this need. This new edition of the book continues the same focus. Its main objective is to provide a foundation for imple menting image processing algorithms using modern software tools. A complemen tary objective is that the book be self-contained and easily readable by individuals with a basic background in digital image processing, mathematical analysis, and computer programming, all at a level typical of that found in a junior/senior cur riculum in a technical discipline. Rudimentary knowledge of MATLAB also is de sirable. To achieve these objectives, we felt that two key ingredients were needed. The first was to select image processing material that is representative of material cov ered in a formal course of instruction in this field. The second was to select soft ware tools that are well supported and documented, and which have a wide range of applications in the "real" world. To meet the first objective, most of the theoretical concepts in the following chapters were selected from Digital Image Processing by Gonzalez and Woods, which has been the choice introductory textbook used by educators all over the world for over three decades. The software tools selected are from the MATLAB® Im�ge Processing Toolbox'", which similarly occupies a position of eminence in both education and industrial applications. A basic strategy followed in the prepa ration of the current edition was to continue providing a seamless integration of well-established theoretical concepts and their implementation using state-of-the art software tools. The book is organized along the same lines as Digital Image Processing. In this way, the reader has easy access to a more detailed treatment of all the image processing concepts discussed here, as well as an up-to-date set of references for further reading. Following this approach made it possible to present theoretical material in a succinct manner and thus we were able to maintain a focus on the software implementation aspects of image processing problem solutions. Because it works in the MATLAB computing environment, the Image Processing Toolbox offers some significant advantages, not only in the breadth of its computational Xlll

- 19. xiv tools, but also because it is supported under most operating systems in use today.A unique feature of this book is its emphasis on showing how to develop new code to enhance existing MATLAB and toolbox functionality. This is an important feature in an area such as image processing, which, as noted earlier, is characterized by the need for extensive algorithm development and experimental work. After an introductionto the fundamentals of MATLAB functions and program ming, the book proceeds to address the mainstream areas of image processing. The major areas covered include intensity transformations, fuzzy image processing, lin ear and nonlinear spatial filtering, the frequency domain filtering, image restora tion and reconstruction, geometric transformations and image registration, color image processing, wavelets, image data compression, morphological image pro cessing, image segmentation, region and boundary representation and description, and object recognition. This material is complemented by numerous illustrations of how to solve image processing problems using MATLAB and toolbox func tions. In cases where a function did not exist, a new function was written and docu mented as part of the instructional focus of the book. Over 120 new functions are included in the following chapters. These functions increase the scope of the Image Processing Toolbox by approximately 40% and also serve the important purpose of further illustrating how to implement new image processing software solutions. The material is presented in textbook format, not as a software manual. Although the book is self-contained, we have established a companion web site (see Section 1.5) designed to provide support in a number of areas. For students following a formal course of study or individuals embarked on a program of self study, the site contains tutorials and reviews on background material, as well as projects and image databases, including all images in the book. For instructors, the site contains classroom presentation materials that include PowerPoint slides of all the images and graphics used in the book. Individuals already familiar with image processing and toolbox fundamentals will find the site a useful place for up-to-date references, new implementation techniques, and a host of other support material not easily found elsewhere. All purchasers of new books are eligible to download executable files of all the new functions developed in the text at no cost. As is true of most writing efforts of this nature, progress continues after work on the manuscript stops. For this reason, we devoted significant effort to the selec tion of material that we believe is fundamental, and whose value is likely to remain applicable in a rapidly evolving body of knowledge. We trust that readers of the book will benefit from this effort and thus find the material timely and useful in their work. RAFAEL C. GONZALEZ RICHARD E. WOODS STEVEN L. EDDINS

- 20. Acknowledgements We are indebted to a number of individuals in academic circles as well as in industry and government who have contributed to the preparation of the book. Their contributions have been important in so many different ways that we find it difficult to acknowledge them in any other way but alphabetically. We wish to extend our appreciation to Mongi A. Abidi, Peter 1. Acklam, Serge Beucher, Ernesto Bribiesca, Michael W. Davidson, Courtney Esposito, Naomi Fernandes, Susan L. Forsburg, Thomas R. Gest, Chris Griffin, Daniel A. Hammer, Roger Heady, Brian Johnson, Mike Karr, Lisa Kempler, Roy Lurie, Jeff Mather, Eugene McGoldrick, Ashley Mohamed, Joseph E. Pascente, David R. Pickens, Edgardo Felipe Riveron, Michael Robinson, Brett Shoelson, Loren Shure, lnpakala Simon, Jack Sklanski, Sally Stowe, Craig Watson, Greg Wolodkin, and Mara Yale. We also wish to acknowledge the organizations cited in the captions of many of the figures in the book for their permission to use that material. R.C.G R. E. W S. L. E xv

- 21. xvi • Acknowledgements The Book Web Site Digital Image Processing Using MATLAB is a self-contained book. However, the companion web site at www.ImageProcessingPlace.com offers additional support in a number of important areas. For the Student or Independent Reader the site contains • Reviews in areas such as MATLAB, probability, statistics, vectors, and matri ces. • Sample computer projects. • A Tutorials section containing dozens of tutorials on most of the topjcs discussed in the book. • A database containing all the images in the book. For the Instructor the site contains • Classroom presentation materials in PowerPoint format. • Numerous links to other educational resources. For the Practitioner the site contains additional specialized topics such as • Links to commercial sites. • Selected new references. • Links to commercial image databases. The web site is an ideal tool for keeping the book current between editions by including new topics, digital images, and other relevant material that has appeared after the book was published. Although considerable care was taken in the produc tion of the book, the web site is also a convenient repository for any errors that may be discovered between printings.

- 22. About the Authors Rafael C. Gonzalez • About the Authors xvn R. C. Gonzalez received the B.S.E.E. degree from the University of Miami in 1965 and the M.E. and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from the Univer sity of Florida, Gainesville, in 1967 and 1970, respectively. He joined the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (UTK) in 1970, where he became Associate Professor in 1973, Professor in 1978, and Distinguished Service Professor in 1984. He served as Chairman of the department from 1994 through 1997. He is currently a Professor Emeritus of Electrical and Computer Science at UTK. He is the founder of the Image & Pattern Analysis Laboratory and the Ro botics & Computer Vision Laboratory at the University of Tennessee. He also founded Perceptics Corporation in 1982 and was its president until 1992. The last three years of this period were spent under a full-time employment contract with Westinghouse Corporation, who acquired the company in 1989. Under his direc tion, Perceptics became highly successful in image processing, computer vision, and laser disk storage technologies. In its initial ten years, Perceptics introduced a series of innovative products,including:The world's first commercially-available comput er vision system for automatically reading the license plate on moving vehicles; a series of large-scale image processing and archiving systems used by the U.S. Navy at six different manufacturing sites throughout the country to inspect the rocket motors of missiles in the Trident II Submarine Program; the market leading family of imaging boards for advanced Macintosh computers; and a line of trillion-byte laser disk products. He is a frequent consultant to industry and government in the areas of pattern recognition,imageprocessing,and machine learning. His academic honors for work in these fields include the 1977 UTK College of Engineering Faculty Achievement Award; the 1978 UTK Chancellor's Research Scholar Award; the 1980 Magnavox Engineering Professor Award; and the 1980 M. E. Brooks Distinguished Professor Award. In 1981 he became an IBM Professor at the University of Tennessee and in 1984 he was named a Distinguished Service Professor there. He was awarded a Distinguished Alumnus Award by the University of Miami in 1985, the Phi Kappa Phi Scholar Award in 1986, and the University of Tennessee's Nathan W. Dough erty Award for Excellence in Engineering in 1992. Honors for industrial accom plishment include the 1987 IEEE Outstanding Engineer Award for Commercial Development in Tennessee; the 1988 Albert Rose National Award for Excellence in Commercial Image Processing; the 1989 B. Otto Wheeley Award for Excellence in Technology Transfer; the 1989 Coopers and Lybrand Entrepreneur of the Year Award; the 1992 IEEE Region 3 Outstanding Engineer Award; and the 1993 Auto mated Imaging Association National Award for Technology Development. Dr. Gonzalez is author or coauthor of over 100 technical articles, two edited books, and five textbooks in the fields of pattern recognition, image processing, and robotics. His books are used in over 1000 universities and research institutions throughout the world. He is listed in the prestigious Marquis Who '.5 Who in Ameri ca, Marquis Who's Who in Engineering, Marquis Who s Who in the World, and in 10

- 23. xviii • About the Authors other national and international biographical citations. He is the co-holder of two U.S. Patents, and has been an associate editor of the IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, and the International Journal of Computer and Information Sciences. He is a member of numerous professional and honorary societies, includ ing Tau Beta Pi, Phi Kappa Phi, Eta Kappa Nu. and Sigma Xi. He is a Fellow of the IEEE. Richard E. Woods Richard E. Woods earned his B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineer ing from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. His professional experiences range from entrepreneurial to the more traditional academic, consulting, govern mental, and industrial pursuits. Most recently, he founded MedData Interactive, a high technology company specializing in the development of handheld computer systems for medical applications. He was also a founder and Vice President of Per ceptics Corporation, where he was responsible for the development of many of the company's quantitative image analysis and autonomous decision making . prod ucts. Prior to Perceptics and MedData, Dr.Woods was anAssistant Professor of Elec trical Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Tennessee and prior to that, a computer applications engineer at Union Carbide Corporation. As a con sultant, he has been involved in the development of a number of special-purpose digital processors for a variety of space and military agencies, including NASA, the Ballistic Missile Systems Command, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Dr. Woods has published numerous articles related to digital signal processing and is coauthor of Digital Image Processing, the leading text in the field. He is a member of several professional societies, including Tau Beta Pi, Phi Kappa Phi, and the IEEE. In 1986, he was recognized as a Distinguished Engineering Alumnus of the University of Tennessee. Steven L. Eddins Steven L. Eddins is development manager of the image processing group at The MathWorks, Inc. He led the development of several versions of the company's Im age Processing Toolbox. His professional interests include building software tools that are based on the latest research in image processing algorithms, and that have a broad range of scientific and engineering applications. Prior to joining The MathWorks, Inc. in 1993, Dr. Eddins was on the faculty of the Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Department at the Univer sity of Illinois, Chicago. There he taught graduate and senior-level classes in digital image processing, computer vision, pattern recognition, and filter design, and he performed research in the area of image compression. Dr. Eddins holds a B.E.E. (1986) and a Ph.D. (1990), both in electrical engineer ing from the Georgia Institute of Technology. He is a senior member of the IEEE.

- 24. Preview Digital image processing is an area characterized by the need for extensive experimental work to establish the viability of proposed solutions to a given problem. In this chapter, we outline how a theoretical foundation and state of-the-art software can be integrated into a prototyping environment whose objective is to provide a set of well-supported tools for the solution of a broad class of problems in digital image processing. DI Background An important characteristic underlying the design of image processing systems is the significant level of testing and experimentation that normally is required before arriving at an acceptable solution. This characteristic implies that the ability to formulate approaches and quickly prototype candidate solutions generally plays a major role in reducing the cost and time required to arrive at a viable system implementation. Little has been written in the way of instructional material to bridge the gap between theory and application in a well-supported software environment for image processing. The main objective of this book is to integrate under one cover a broad base of theoretical concepts with the knowledge required to im plement those concepts using state-of-the-art image processing software tools. The theoretical underpinnings of the material in the following chapters are based on the leading textbook in the field: Digital Image Processing, by Gon zalez and Woods.t The software code and supporting tools are based on the leading software in the field: MATLAB® and the Image Processing Toolbox"' t R. C. Gonzalez and R. E. Woods, Digital Image Processing, 3rd ed., Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River. NJ, 2!Xl8. 1

- 25. 2 Chapter 1 • Introduction We use 1he term c11swm funNion 10 denole a function developed in the book. as opposed to a "standard" MATLAB or Image Processing Toolhox function. from The MathWorks, Inc. (see Section 1.3). The material in the book shares the same design, notation, and style of presentation as the Gonzalez-Woods text, thus simplifying cross-referencing between the two. The book is self-contained. To master its contents, a reader should have introductory preparation in digital image processing, either by having taken a formal course of study on the subject at the senior or first-year graduate level, or by acquiring the necessary background in a program of self-study. Familiar ity with MATLAB and rudimentary knowledge ofcomputer programming are assumed also. Because MATLAB is a matrix-oriented language, basic knowl edge of matrix analysis is helpful. The book is based on principles. It is organized and presented in a text book format, not as a manual. Thus, basic ideas of both theory and software are explained prior to the development of any new programming concepts. The material is illustrated and clarified further by numerous examples rang ing from medicine and industrial inspection to remote sensing and astronomy. This approach allows orderly progression from simple concepts to sophisticat ed implementation of image processing algorithms. However, readers already familiar with MATLAB, the Image Processing Toolbox, and image processing fundamentals can proceed directly to specific applications of interest, in which case the functions in the book can be used as an extension of the family of tool box functions. All new functions developed in the book are fully documented, and the code for each is included either in a chapter or in Appendix C. Over 120 custom functions are developed in the chapters that follow. These functions extend by nearly 45% the set of about 270 functions in the Image Processing Toolbox. In addition to addressing specific applications, the new functions are good examples of how to combine existing MATLAB and tool box functions with new code to develop prototype solutions to a broad spec trum of problems in digital image processing. The toolbox functions, as well as the functions developed in the book, run under most operating systems. Consult the book web site (see Section 1.5) for a complete list. ID What Is Digital Image Processing? An image may be defined as a two-dimensional function, f(x, y). where x and y are spatial coordinates, and the amplitude offat any pair of coordinates (x, y) is called the intensity or gray level of the image at that point. When x, y, and the amplitude values off are all finite, discrete quantities, we call the image a digital image. The field of digital image processing refers to processing digital images by means of a digital computer. Note that a digital image is composed of a finite number of elements, each of which has a particular location and value. These elements are referred to as picture elements, image elements,pels, and pixels. Pixel is the term used most widely to denote the elements of a digi tal image. We consider these definitions formally in Chapter 2. Vision is the most advanced of our senses, so it is not surprising that im ages play the single most important role in human perception. However, un like humans, who are limited to the visual band of the electromagnetic (EM)

- 26. 1.2 • What Is Digital Image Processing? 3 spectrum, imaging machines cover almost the entire EM spectrum, ranging from gamma to radio waves. They can operate also on images generated by sources that humans do not customarily associate with images. These include ultrasound, electronmicroscopy, and computer-generated images.Thus, digital image processiHg encompasses a wide and varied field of applications. There is no general agreement among authors regarding where image pro cessing stops and other related areas, such as image analysis and computer vision, begin. Sometimes a distinction is made by defining image processing as a discipline in which both the input and output of a process are images. We believe this to be a limiting and somewhat artificial boundary. For example, under this definition, even the trivial task of computing the average intensity of an image would not be considered an image processing operation. On the other hand, there are fields, such as computer vision, whose ultimate goal is to use computers to emulate human vision, including learning and being able to make inferences and take actions based on visual inputs. This area itself is a branch of artificial intelligence (AI), whose objective is to emulate human intelligence.The field of AI is in its infancy in terms of practical developments, with progress having been much slower than originally anticipated.The area of image analysis (also called image understanding) is in between image process ing and computer vision. There are no clear-cut boundaries in the continuum from image processing at one end to computer vision at the other. However, a useful paradigm is to consider three types of computerized processes in this continuum: low-, mid ' and high-level processes. Low-level processes involve primitive operations, such as image preprocessing to reduce noise, contrast enhancement, and image sharpening. A low-level process is characterized by the fact that both its inputs and outputs typically are images. Mid-level processes on images involve tasks such as segmentation (partitioning an image into regions or objects), descrip tion of those objects to reduce them to a form suitable for computer process ing, and classification (recognition) of individual objects. A mid-level process is characterized by the fact that its inputs generally are images, but its out puts are attributes extracted from those images (e.g., edges, contours, and the identity of individual objects). Finally, high-level processing involves "making sense" ofan ensemble ofrecognized objects, as in image analysis, and, at the far end of the continuum, performing the cognitive functions normally associated with human vision. Based on the preceding comments, we see that a logical place of overlap between image processing and image analysis is the area of recognition of in dividual regions or objects in an image. Thus, what we call in this book digital image processing encompasses processes whose inputs and outputs are images and, in addition.encompasses processes that extract attributes from images, up to and including the recognition of individual objects. As a simple illustration to clarify these concepts, consider the area of automated analysis of text. The processes of acquiring an image of a region containing the text, preprocessing that image, extracting (segmenting) the individual characters, describing the characters in a form suitable for computer processing, and recognizing those

- 27. 4 Chapter 1 • Introduction As we discuss in more detail in Chapter 2. images may be treated as matrices. thus making MATLAB software a natural choice for image processing applications. individual characters, are in the scope of what we call digital image processing in this book. Making sense of the content of the page may be viewed as being in the domain of image analysis and even computer vision, depending on the level of complexity implied by the statement "making sense of." Digital image processing, as we have defined it, is used successfully in a broad range of areas of exceptional social and economic value. Ill Background on MATLAB and the Image Processing Toolbox MATLAB is a high-performance language for technical computing. It inte grates computation, visualization, and programming in an easy-to-use environ ment where problems and solutions are expressed in familiar mathematical notation. Typical uses include the following: • Math and computation • Algorithm development • Data acquisition • Modeling, simulation, and prototyping • Data analysis, exploration, and visualization • Scientific and engineering graphics • Application development, including building graphical user interfaces MATLAB is an interactive system whose basic data element is a matrix. This allows formulating solutions to many technical computing problems, especially those involving matrix representations, in a fraction of the time it would take to write a program in a scalar non-interactive language such as C. The name MATLAB stands for Matrix Laboratory. MATLAB was written originally to provide easy access to matrix and linear algebra software that previously required writing FORTRAN programs to use. Today, MATLAB incorporates state of the art numerical computation software that is highly optimized for modern processors and memory architectures. In university environments, MATLAB is the standard computational tool for introductory and advanced courses in mathematics, engineering, and sci ence. In industry, MATLAB is the computational tool of choice for research, development, and analysis. MATLAB is complemented by a family of appli cation-specific solutions called toolboxes. The Image Processing Toolbox is a collection of MATLAB functions (called M-functions or M-files) that extend the capability of the MATLAB environment for the solution of digital image processing problems. Other toolboxes that sometimes are used to complement the Image Processing Toolbox are the Signal Processing, Neural Networks, Fuzzy Logic, and Wavelet Toolboxes. The MATLAB & Simulink Student Version is a product that includes a full-featured version of MATLAB, the Image Processing Toolbox, and several other useful toolboxes. The Student Version can be purchased at significant discounts at university bookstores and at the MathWorks web site (www.mathworks.com).

- 28. 1.4 • Areas of Image Processing Covered in the Book 5 DI Areas of Image Processing Covered in the Book Every chapter in the book contains the pertinent MATLAB and Image Pro cessing Toolbox material needed to implement the image processing methods discussed. Whef! a MATLAB or toolbox function does not exist to implement a specific method, a custom function is developed and documented. As noted earlier, a complete listing of every new function is available. The remaining twelve chapters cover material in the following areas. Chapter 2: Fundamentals. This chapter covers the fundamentals of MATLAB notation, matrix indexing, and programming concepts. This material serves as foundation for the rest of the book. Chapter 3: Intensity Transformations and Spatial Filtering. This chapter covers in detail how to use MATLAB and the Image Processing Toolbox to imple ment intensity transformation functions. Linear and nonlinear spatial filters are covered and illustrated in detail. We also develop a set of basic functions for fuzzy intensity transformations and spatial filtering. Chapter 4: Processing in the Frequency Domain. The material in this chapter shows how to use toolbox functions for computing the forward and inverse 2-D fast Fourier transforms (FFTs), how to visualize the Fourier spectrum, and how to implement filtering in the frequency domain. Shown also is a method for generating frequency domain filters from specified spatial filters. Chapter 5: Image Restoration. Traditional linear restoration methods, such as the Wiener filter, are covered in this chapter. Iterative, nonlinear methods, such as the Richardson-Lucy method and maximum-likelihood estimation for blind deconvolution, are discussed and illustrated. Image reconstruction from projections and how it is used in computed tomography are discussed also in this chapter. Chapter 6: Geometric Transformations and Image Registration. This chap ter discusses basic forms and implementation techniques for geometric im age transformations, such as affine and projective transformations. Interpola tion methods are presented also. Different image registration techniques are discussed, and several examples of transformation, registration, and visualiza tion methods are given. Chapter 7: Color Image Processing. This chapter deals with pseudocolor and full-color image processing. Color models applicable to digital image process ing are discussed, and Image ProcessingToolbox functionality in color process ing is extended with additional color models. The chapter also covers applica tions of color to edge detection and region segmentation.

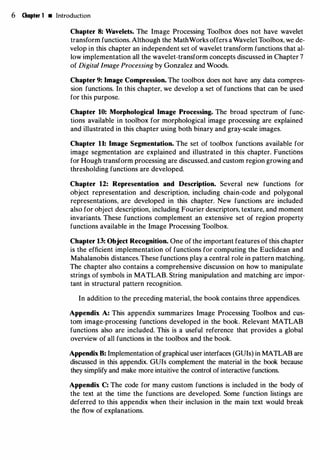

- 29. 6 Chapter 1 • Introduction Chapter 8: Wavelets. The Image Processing Toolbox does not have wavelet transform functions. Although the MathWorks offers a WaveletToolbox, we de velop in this chapter an independent set of wavelet transform functions that al low implementation all the wavelet-transform concepts discussed in Chapter 7 of Digital Image Processing by Gonzalez and Woods. Chapter 9: Image Compression. The toolbox does not have any data compres sion functions. In this chapter, we develop a set of functions that can be used for this purpose. Chapter 10: Morphological Image Processing. The broad spectrum of func tions available in toolbox for morphological image processing are explained and illustrated in this chapter using both binary and gray-scale images. Chapter 11: Image Segmentation. The set of toolbox functions available for image segmentation are explained and illustrated in this chapter. Functions for Hough transform processing are discussed, and custom region growing and thresholding functions are developed. Chapter 12: Representation and Description. Several new functions for object representation and description, including chain-code and polygonal representations, are developed in this chapter. New functions are included also for object description, including Fourier descriptors, texture, and moment invariants. These functions complement an extensive set of region property functions available in the Image Processing Toolbox. Chapter 13: Object Recognition. One of the important features of this chapter is the efficient implementation of functions for computing the Euclidean and Mahalanobis distances.These functions play a central role in pattern matching. The chapter also contains a comprehensive discussion on how to manipulate strings of symbols in MATLAB. String manipulation and matching are impor tant in structural pattern recognition. In addition to the preceding material, the book contains three appendices. Appendix A: This appendix summarizes Image Processing Toolbox and cus tom image-processing functions developed in the book. Relevant MATLAB functions also are included. This is a useful reference that provides a global overview of all functions in the toolbox and the book. Appendix B: Implementation ofgraphical user interfaces (GUis) in MATLAB are discussed in this appendix. GUis complement the material in the book because they simplify and make more intuitive the control of interactive functions. Appendix C: The code for many custom functions is included in the body of the text at the time the functions are developed. Some function listings are deferred to this appendix when their inclusion in the main text would break the flow of explanations.

- 30. I.S • The Book Web Site 7 Ill The Book Web Site An important feature of this book is the support contained in the book web site.The site address is www.lmageProcessingPlace.com This site provides support to the book in the following areas: • Availability of M-files, including executable versions of all M-files in the book • Tutorials • Projects • Teaching materials • Links to databases, including all images in the book • Book updates • Background publications The same site also supports the Gonzalez-Woods book and thus offers comple mentary support on instructional and research topics. 11:1 Notation Equations in the book are typeset using familiar italic and Greek symbols, as in f(x, y) = A sin(ux + vy) and cfJ(u, v) = tan-1 [l(u, v)/R(u, v)]. All MATLAB function names and symbols are typeset in monospace font, as in fft2 ( f ) , logical (A) , and roipoly ( f , c , r ) . The first occurrence of a MATLAB or Image Processing Toolbox function is highlighted by use of the following icon on the page margin: Similarly, the first occurrence of a new (custom) function developed in the book is highlighted by use of the following icon on the page margin: function name w The symbol w is used as a visual cue to denote the end of a function listing. When referring to keyboard keys, we use bold letters, such as Return and Tab. We also use bold letters when referring to items on a computer screen or menu, such as File and Edit. ID The MATLAB Desktop The MATLAB Desktop is the main working environment. It is a set of graph ics tools for tasks such as running MATLAB commands, viewing output, editingand managingfiles and variables,and viewingsession histories.Figure 1.1 shows the MATLAB Desktop in the default configuration. The Desktop com-

- 31. 8 Chapter 1 • Introduction ponents shown are the Command Window, the Workspace Browser, the Cur rent Directory Browser, and the Command History Window. Figure 1.1 also shows a Figure Window, which is used to display images and graphics. The Command Window is where the user types MATLAB commands at the prompt (»). For example, a user can call a MATLAB function, or assign a value to a variable. The set of variables created in a session is called the Workspace, and their values and properties can be viewed in the Workspace Browser. Directories are called Jolt/er.· in Windows. The top-most rectangular window shows the user's CurrentDirectory,which typically contains the path to the files on which a user is working at a given time. The current directory can be changed using the arrow or browse button (" . . . ") to the right of the Current Directory Field. Files in the Current Direc tory can be viewed and manipulated using the Current Directory Browser. Current Directory Field I « dipum ...-�-- » f - imread ( ' ros e_S 12 . tif ' ) ; » imshc:w(f) D Name • Oat.. fa.. » 10/,., A fl Contrnts.m fl conwaylaws.m � covmaitrix.m Command Window 'WI t:J dftcorr.m !) dftfilt.m fl dftuv.m 10/... � diamrtrr.m 10/... fl rndpoints.m 10/... fl rntropy.m 10/... fl fchcodr.m 10/... fl frdmp.m 10/... E13 fuzzyrdgny>.mat 10/... fl fuzzyf iltm 10/... ... defuzzify.m (M-File) V l�UZZIFYOutput of fuzzy trm. d•fuzzify(Qa, vrang•) I_ � Cunent Directory Browser FIGURE 1.1 The MATLAB Desktop with its typical components. Valu• <512x512 uint8> Workspace Browser Comm•nd to �• Cl � X I '· f = m 2gray(I ) ; ell %-- 11/17 8 3 :41 PM I. f-f = imre ( ' rose . tii f.. imshc:w(f) I L imwrite (imresize (f , � �..·%- - 11/ 17/08 3 :45 PM 8 %-- 11/17/08 3 : 47 PM t1. f = imresize ( " rose_: .. clc 1-·f = imread ( " rose_si.; 1:3 • imshc:w(f)

- 32. 1.7 • The MATLAB Desktop 9 The Command History Window displays a log of MATLAB statements executed in the Command Window. The log includes both current and previ ous sessions. From the Command History Window a user can right-click on previous statements to copy them, re-execute them, or save them to a file. These features 'Bfe useful for experimenting with various commands in a work session, or for reproducing work performed in previous sessions. The MATLAB Desktop may be configured to show one, several, or all these tools, and favorite Desktop layouts can be saved for future use. Table 1.1 sum marizes all the available Desktop tools. MATLAB uses a search path to find M-files and other MATLAB-related files, which are organized in directories in the computer file system. Any file run in MATLAB must reside in the Current Directory or in a directory that is on the search path. By default, the files supplied with MATLAB and Math Works toolboxes are included in the search path.The easiest way to see which directories are on the search path, or to add or modify a search path, is to select Set Path from the File menu on the desktop, and then use the Set Path dialog box. It is good practice to add commonly used directories to the search path to avoid repeatedly having to browse to the location of these directories. Typing clear at the prompt removes all variables from the workspace. This frees up system memory. Similarly, typing clc clears the contents of the com mand window. See the help page for other uses and syntax forms. Tool Array Editor Command History Window Command Window Current Directory Browser Current Directory Field Editor/Debugger Figure Windows File Comparisons Help Browser Profiler Start Button Web Browser Workspace Browser Description View and edit array contents. View a log of statements entered in the Command Window; search for previously executed statements, copy them, and re-execute them. Run MATLAB statements. View and manipulate files in the current directory. Shows the path leading to the current directory. Create, edit, debug, and analyze M-files. Display, modify, annotate, and print MATLAB graphics. View differences between two files. View and search product documentation. Measure execution time of MATLAB functions and lines; count how many times code lines are executed. Run product tools and access product documentation and demos. View HTML and related files produced by MATLAB or other sources. View and modify contents of the workspace. TABLE 1.1 MATLAB desktop tools.

- 33. 10 Chapter 1 • Introduction 1.7.l Using the MATLAB Editor/Debugger The MATLAB Editor/Debugger (or just the Editor) is one of the most impor tant and versatile of the Desktop tools. Its primary purpose is to create and edit MATLAB function and script files. These files are called M-files because their filenames use the extension . m, as in pixeldup . m. The Editor highlights different MATLAB code elements in color; also, it analyzes code to offer suggestions for improvements. The Editor is the tool of choice for working with M-files. With the Editor, a user can set debugging breakpoints, inspect variables during code execution, and step through code lines. Finally, the Editor can publish MATLAB M-files and generate output to formats such as HTML, LaTeX, Word, and PowerPoint. To open the editor, type edit at the prompt in the Command Window. Simi larly, typing edit filename at the prompt opens the M-file filename . m in an editor window, ready for editing.The file must be in the current directory, or.in a directory in the search path. 1.7.2 Getting Help The principal way to get help is to use the MATLAB Help Browser, opened as a separate window either by clicking on the question mark symbol (?) on the desktop toolbar, or by typing doc (one word) at the prompt in the Com mand Window. The Help Browser consists of two panes, the help navigator pane, used to find information, and the display pane, used to view the informa tion. Self-explanatory tabs on the navigator pane are used to perform a search. For example, help on a specific function is obtained by selecting the Search tab and then typing the function name in the Search for field. It is good practice to open the Help Browser at the beginning of a MATLAB session to have help readily available during code development and other MATLAB tasks. Another way to obtain help for a specific function is by typing doc fol lowed by the function name at the command prompt. For example, typing doc file_name displays the reference page for the function called file_name in the display pane of the Help Browser.This command opens the browser if it is not open already.The doc function works also for user-written M-files that contain help text. See Section 2.10.l for an explanation of M-file help text. When we introduce MATLAB and Image Processing Toolbox functions in the following chapters, we often give only representative syntax forms and descriptions. This is necessary either because of space limitations or to avoid deviating from a particular discussion more than is absolutely necessary. In these cases we simply introduce the syntax required to execute the function in the form required at that point in the discussion. By being comfortable with MATLAB documentation tools, you can then explore a function of interest in more detail with little effort. Finally, the MathWorks' web site mentioned in Section 1 .3 contains a large database of help material, contributed functions, and other resources that

- 34. 1.8 • How References Are Organized in the Book 11 should be utilized when the local documentation contains insufficient infor mation about a desired topic. Consult the book web site (see Section 1.5) for additional MATLAB and M-function resources. 1.7.3 Saving ahd Retrieving Work Session Data There are several ways to save or load an entire work session (the contents of the Workspace Browser) or selected workspace variables in MATLAB. The simplest is as follows: To save the entire workspace, right-click on any blank space in the Workspace Browser window and select Save Workspace As from the menu that appears. This opens a directory window that allows naming the file and selecting any folder in the system in which to save it. Then click Save. To save a selected variable from the Workspace, select the variable with a left click and right-click on the highlighted area. Then select Save Selection As from the menu that appears. This opens a window from which a folder can be selected to save the variable.To select multiple variables, use shift-click or con trol-click in the familiar manner, and then use the procedure just described for a single variable. All files are saved in a binary format with the extension . mat. These saved files commonly are referred to as MAT-files, as indicated earlier. For example, a session named, say, mywork_2009_02_10, would appear as the MAT-file mywork_2009_02_1O.mat when saved. Similarly, a saved image called final_image (which is a single variable in the workspace) will appear when saved as final_image.mat. To load saved workspaces and/or variables, left-click on the folder icon on the toolbar of the Workspace Browser window. This causes a window to open from which a folder containing the MAT-files of interest can be selected. Dou ble-clicking on a selected MAT-file or selecting Open causes the contents of the file to be restored in the Workspace Browser window. It is possible to achieve the same results described in the preceding para graphs by typing save and load at the prompt, with the appropriate names and path information.This approach is not as convenient, but it is used when formats other than those available in the menu method are required. Func tions save and load are useful also for writing M-files that save and load work space variables.As an exercise,you are encouraged to use the Help Browser to learn more about these two functions. Ill How References Are Organized in the Book All references in the book are listed in the Bibliography by author and date, as in Soille [2003]. Most of the background references for the theoretical con tent of the book are from Gonzalez and Woods [2008]. In cases where this is not true, the appropriate new references are identified at the point in the discussion where they are needed. References that are applicable to all chap ters, such as MATLAB manuals and other general MATLAB references, are so identified in the Bibliography.

- 35. 12 Chapter 1 • Introduction Summary In addition to a briefintroduction to notation and basicMATLAB tools, the material in this chapter emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive prototyping environment in the solution of digital image processing problems. In the following chapter we begin to lay the foundation needed to understand Image Processing Toolbox functions and introduce a set of fundamental programming concepts that are used throughout the book. The material in Chapters 3 through 13 spans a wide cross section of topics that are in the mainstream of digital image processing applications. However, although the topics covered are varied, the discussion in those chapters follows the same basic theme of demonstrating how combining MATLAB and toolbox functions with new code can be used to solve a broad spectrum of image-processing problems.

- 36. Preview As mentioned in the previous chapter, the power that MATLAB brings to digital image processing is an extensive set of functions for processing mul tidimensional arrays of which images (two-dimensional numerical arrays) are a special case. The Image Processing Toolbox is a collection of functions that extend the capability of the MATLAB numeric computing environment. These functions, and the expressiveness of the MATLAB language, make image-processing operations easy to write in a compact, clear manner, thus providing an ideal software prototyping environment for the solution of image processing problems. In thischapterwe introduce the basics ofMATLAB notation, discuss a number of fundamental toolbox properties and functions, and begin a discussion of programming concepts. Thus, the material in this chapter is the foundation for most of the software-related discussions in the remainder of the book. ID Digital Image Representation An image may be defined as a two-dimensional function f(x, y), where x and y are spatial (plane) coordinates, and the amplitude off at any pair of coordi nates is called the intensity of the image at that point.The term gray levelis used often to refer to the intensity of monochrome images. Color images are formed by a combination of individual images. For example, in the RGB color system a color image consists of three individual monochrome images, referred to as the red (R), green (G), and blue (B) primary (or component) images. For this reason, many of the techniques developed for monochrome images can be ex tended to color images by processing the three component images individually. Color image processing is the topic of Chapter 7. An image may be continuous 13

- 37. 14 Chapter 2 • Fundamentals a b FIGURE 2.1 Coordinate conventions used (a) in many image processing books, and (b) in the Image Processing Toolbox. with respect to the x- and y-coordinates, and also in amplitude. Converting such an image to digital form requires that the coordinates, as well as the amplitude, be digitized. Digitizing the coordinate values is called sampling; digitizing the amplitude values is called quantization. Thus, when x, y, and the amplitude val ues offare all finite, discrete quantities, we call the image a digital image. 2.1.1 Coordinate Conventions The result ofsampling and quantization is a matrix of real numbers.We use two principal ways in this book to represent digital images. Assume that an image f(x, y) is sampled so that the resulting image has M rows and N columns. We say that the image is ofsize M X N. The values of the coordinates are discrete quantities. For notational clarity and convenience, we use integer values for these discrete coordinates. In many image processing books, the image origin is defined to be at (x, y) = (0, 0).The next coordinate values along the first row of the image are (x, y) = (0, 1). The notation (0, 1 ) is used to signify the second sample along the first row. It does not mean that these are the actual values of physical coordinates when the image was sampled. Figure 2.1 (a) shows this coordinate convention. Note that x ranges from 0 to M - 1 and y from 0 to N - 1 in integer increments. The coordinate convention used in the Image ProcessingToolbox to denote arrays is different from the preceding paragraph in two minor ways. First, in stead of using (x, y), the toolbox uses the notation (r,c) to indicate rows and columns. Note, however, that the order of coordinates is the same as the order discussed in the previous paragraph, in the sense that the first element of a coordinate tuple, (a,b), refers to a row and the second to a column. The other difference is that the origin of the coordinate system is at (r,c) = ( 1, 1); thus, r ranges from 1 to M, and c from 1 to N, in integer increments. Figure 2.1 (b) il lustrates this coordinate convention. Image Processing Toolbox documentation refers to the coordinates in Fig. 2.l(b) as pixel coordinates. Less frequently, the toolbox also employs another coordinate convention, called spatialcoordinates,that usesxtoreferto columns and y to refers to rows.This is the opposite of our use of variables x and y. With 0 I 2 . . . . 0 I o�igi� 2 . . . . . . . . . . . M - 1 . . . . . . One pixel _/ x · · · · N - 1 y 2 3 . M I 2 3 . . . . � . . • O�igi� r . . . . . One pixel _/ . . . . N c .

- 38. 2.2 • Images as Matrices 15 a few exceptions, we do not use the toolbox's spatial coordinate convention in this book, but many MATLAB functions do, and you will definitely encounter it in toolbox and MATLAB documentation. 2.1.2 Images as Matrices The coordinate system in Fig. 2. 1 (a) and the preceding discussion lead to the following representation for a digitized image: f(x, y) f(O,O) f(l,O) f(O, l) f(l, l) f(M - 1,0) f(M - l, l) f(O, N - 1) f(I, N - 1) f(M - l, N - 1) The right side of this equation is a digital image by definition. Each element of this array is called an image element,picture element,pixel, orpet.The terms image and pixel are used throughout the rest of our discussions to denote a digital image and its elements. A digital image can be represented as a MATLAB matrix: MATLAB f ( 1 , 1 ) f ( 1 , 2 ) f = f ( 2 , 1 ) f ( 2 , 2 ) f ( M , 1 ) f ( M , 2 ) f ( 1 I N ) f ( 2 , N ) f ( M , N ) where f ( 1 , 1 ) = f(O,O) (note the use of a monospace font to denote MAT LAB quantities). Clearly, the two representations are identical, except for the shift in origin.The notation f ( p , q ) denotes the element located in row p and column q. For example, f ( 6 , 2 ) is lhe element in the sixth row and second column of matrix f. Typically, we use the letters M and N, respectively, to denote the number of rows and columns in a matrix. A 1 x N matrix is called a row vec tor, whereas an M x 1 matrix is called a column vector. A 1 x 1 matrix is a scalar. Matrices in MATLAB are stored in variables with names such as A, a, RGB, real_array, and so on. Variables must begin with a letter and contain only letters, numerals, and underscores. As noted in the previous paragraph, all MATLAB quantities in this book are written using monospace characters. We use conventional Roman, italic notation, such as f(x, y), for mathematical ex pressions. ID Reading Images Images are read into the MATLAB environment using function imread,whose basic syntax is imread ( ' filename ' ) documenlation uses the terms matrix anc..l army interchangeably. However. keep in mind that a matrix is two dimensional,whereas an array can have any finite dimension. Recall from Section 1 .6 that we use margin icons to highlight the first use of a MATLAB or toolbox function.

- 39. 16 Chapter 2 • Fundamentals In Windows, directories arc calledfohler.L Here, filename is a string containing the complete name of the image file (in cluding any applicable extension). For example, the statement >> f = imread ( ' chestxray . j pg ' ) ; reads the image from the JPEG file chestxray into image array f. Note the use of single quotes ( ' ) to delimit the string filename. The semicolon at the end of a statement is used by MATLAB for suppressing output. If a semicolon is not included, MATLAB displays on the screen the results of the operation(s) specified in that line. The prompt symbol (») designates the beginning of a command line, as it appears in the MATLAB Command Window (see Fig. 1.1). When, as in the preceding command line, no path information is included in filename, imread reads the file from the Current Directory and, if that fails, it tries to find the file in the MATLAB search path (see Section 1.7).Th� simplest way to read an image from a specified directory is to include a full or relative path to that directory in filename. For example, >> f = imread ( ' D : myimages chestxray . j pg ' ) ; reads the image from a directory called myimages in the D: drive, whereas >> f = imread ( ' . myimages chestxray . j pg ' ) ; reads the image from the myimages subdirectory of the current working direc tory. The MATLAB Desktop displays the path to the Current Directory on the toolbar, which provides an easy way to change it. Table 2.1 lists some of the most popular image/graphics formats supported by imread and imwrite (imwrite is discussed in Section2.4). Typing size at the prompt gives the row and column dimensions of an image: » size ( f ) ans 1 024 1 024 More generally, for an array A having an arbitrary number of dimensions, a statement of the form [ D1 ' D2 , . . . ' DK] = size (A) returns the sizes of the first K dimensions of A. This function is particularly use ful in programming to determine automatically the size of a 2-D image: » [ M , N J = size ( f ) ; This syntax returns the number of rows (M) and columns (N) in the image. Simi larly, the command

- 40. 2.2 • Reading Images 17 Format Recognized Name Description Extensions BM Pt Windows Bitmap . bmp CUR Windows Cursor Resources . cu r FITSt Flexible Image Transport System . fts , . fits GIF Graphics Interchange Format . gif HOF Hierarchical Data Format . hdf 1cot Windows Icon Resources . ico JPEG Joint Photographic Experts Group . j pg , . i peg JPEG 20001 Joint Photographic Experts Group . j p2 ' . j pf ' . j px , j 2c , j 2k PBM Portable Bitmap . pbm PGM Portable Graymap . pgm PNG Portable Network Graphics . png PNM Portable Any Map . pnm RAS Sun Raster . ras TIFF Tagged Image File Format . tif ' . t iff XWD X Window Dump . xwd 'Supported by imread, but not by imwrite » M = size ( f , 1 ) ; gives the size of f along its first dimension, which is defined by MATLAB as the vertical dimension. That is, this command gives the number of rows in f. The second dimension of an array is in the horizontal direction, so the state ment size ( f , 2 ) gives the number of columns in f. A singleton dimension is any dimension, dim, for which size (A, dim ) = 1 . The whos function displays additional information about an array. For instance, the statement >> whos f gives Name f Size Bytes 1 024x1 024 1 048576 Class uintB Attributes The Workspace Browser in the MATLAB Desktop displays similar informa tion. The uintB entry shown refers to one of several MATLAB data classes discussed in Section 2.5. A semicolon at the end of a whos line has no effect, so normally one is not used. TABLE 2.1 Some of the image/graphics formats support ed by imread and imwrite, starting with MATLAB 7.6. Earlier versions support a subset of these formats. See the MATLAB docu mentation for a complete list of supported formats. Although not applicable in this example. attributes that might appear under Attributes include terms such as global. complex, and sparse.

- 41. 18 Chapter 2 • Fundamentals Function imshow has a number or olher syntax forms for performing tasks such as controlling image magnification. Consult the help page for imshow for additional details. EXAMPLE 2.1: Reading and displaying images. FIGURE 2.2 Screen capture showing how an image appears on the MATLAB desktop. Note the figure number on the top, left of the window. In most of the examples throughout the book, only the images themselves arc shown. ID Displaying Images Images are displayed on the MATLAB desktop using function imshow, which has the basic syntax: imshow( f ) where f is an image array. Using the syntax imshow ( f , [ low high ] ) displays as black all values less than or equal to low, and as white all values greater than or equal to high. The values in between are displayed as interme diate intensity values. Finally, the syntax imshow ( f , [ ] ) sets variable low to the minimum value of array f and high to its maximum value. This form of imshow is useful for displaying images that have a low dynamic range or that have positive and negative values. • The following statements read from disk an image called rose_51 2 . tif, extract information about the image, and display it using imshow: >> f = imread ( ' rose_51 2 . tif ' ) ; >> whos f Name f » imshow ( f ) Size 51 2x51 2 Bytes 2621 44 Class Attributes uintB array A semicolon at the end of an imshow line has no effect, so normally one is not used. Figure 2.2 shows what the output looks like on the screen. The figure [- ,- . � - - .- - - - - - - - - - o � �r

- 42. 2.3 • Displaying Images 19 number appears on the top, left of the window. Note the various pull-down menus and utility buttons.They are used for processes such as scaling, saving, and exporting the contents of the display window. In particular, the Edit menu has functions for editing and formatting the contents before they are printed or saved to disk·. If another image, g, is displayed using imshow, MATLAB replaces the image in the figure window with the new image. To keep the first image and output a second image, use function figure, as follows: >> figure , imshow ( g ) Using the statement >> imshow ( f ) , figure , imshow ( g ) displays both images. Note that more than one command can be written on a line. provided that different commands are delimited by commas or semico lons. As mentioned earlier, a semicolon is used whenever it is desired to sup press screen outputs from a command line. Finally, suppose that we have just read an image, h, and find that using imshow(h) produces the image in Fig.2.3(a).This image has a low dynamic range, a condition that can be remedied for display purposes by using the statement >> imshow ( h , [ ] ) Figure 2.3(b) shows the result. The improvement is apparent. • The Image Tool in the Image Processing Toolbox provides a more interac tive environment for viewing and navigating within images, displaying detailed information about pixel values, measuring distances, and other useful opera tions. To start the Image Tool, use the imtool function. For example, the fol lowing statements read an image from a file and then display it using imtool: >> f = imread ( ' rose_1 024 . tif ' ) ; » imtool ( f ) Function figure creates a figure window. When used without an argument, as shown here. it simply creates a new figure window. Typing figure ( n ) forces figure number n to become visible. �tool a b FIGURE 2.3 (a) An image, h, with low dynamic range. (b) Result of scaling by using imshow ( h , [ I ) . (Original image courtesy of Dr. David R. Pickens, Vanderbilt University Medical Center.)

- 43. 20 Chapter 2 • Fundamentals FIGURE2.4The Image Tool. The Overview Window, Main Window, and Pixel Region tools are shown. Figure 2.4 shows some of the windows that might appear when using the Image Tool.The large, central window is the main view. In the figure, it is show ing the image pixels at 400% magnification, meaning that each image pixel is rendered on a 4 X 4 block of screen pixels.The status text at the bottom of the main window shows the column/row location (701, 360) and value ( 181 ) of the pixel lying under the mouse cursor (the origin of the image is at the top, left). The Measure Distance tool is in use, showing that the distance between the two pixels enclosed by the small boxes is 25.65 units. The Overview Window, on the left side of Fig. 2.4, shows the entire image in a thumbnail view. The Main Window view can be adjusted by dragging the rectangle in the Overview Window.The Pixel Region Window shows individual pixels from the small square region on the upper right tip of the rose, zoomed large enough to see the actual pixel values. Table 2.2 summarizes the various tools and capabilities associated with the Image Tool. In addition to the these tools, the Main and Overview Win dow toolbars provide controls for tasks such as image zooming, panning, and scrolling.

- 44. 2.4 • Writing Images 21 Tool Description Pixel Information Displays information about the pixel under the mouse pointer. Pixel Region Distance Image Information Adjust Contrast Crop Image Display Range Overview Superimposes pixel values on a zoomed-in pixel view. Measures the distance between two pixels. Displays information about images and image files. Adjusts the contrast of the displayed image. Defines a crop region and crops the image. Shows the display range of the image data. Shows the currently visible image. DJ Writing Images Images are written to the Current Directory using function imwrite, which has the following basic syntax: imwrite ( f , ' filename ' ) With this syntax, the string contained in filename must include a recognized file format extension (see Table 2.1). For example, the following command writes f to a file called patient1 0_run1 . tif: » imwrite ( f , ' patient1 0_run1 . t if ' ) Function imwrite writes the image as a TIFF file because it recognizes the . tif extension in the filename. Alternatively, the desired format can be specified explicitly with a third in put argument. This syntax is useful when the desired file does not use one of the recognized file extensions.For example, the following command writes f to a TIFF file called patient1 O . run 1 : » imwrite ( f , ' patient1 0 . run1 ' , ' tif ' ) Function imwrite can have other parameters, depending on the file format selected. Most of the work in the following chapters deals either with JPEG or TIFF images, so we focus attention here on these two formats. A more general imwrite syntax applicable only to JPEG images is imwrite ( f , ' filename . j pg ' , ' quality ' , q ) where q is an integer between 0 and 100 (the lower the number the higher the degradation due to JPEG compression). TABLE 2.2 Tools associated with the Image Tool.

- 45. 22 Chapter 2 • Fundamentals EXAMPLE 2.2: Writing an image and using function imfinfo. a b c d e f FIGURE 2.5 (a) Original image. (b) through (f) Results of using j pg quality values q = 50, 25, 1 5, 5, and 0, respectively. False contouring begins to be noticeable for q = 1 5 [image (d)] and is quite visible for q = 5 and q = 0. See Example 2. 1 1 [or a function that creates all the images in Fig. 2.5 using a loop. • Figure 2.5(a) shows an image, f, typical of sequences of images resulting from a given chemical process. It is desired to transmit these images on a rou tine basis to a central site for visual and/or automated inspection. In order to reduce storage requirements and transmission time, it is important that the images be compressed as much as possible, while not degrading their visual

- 46. 2.4 • Writing Images 23 appearance beyond a reasonable level. In this case "reasonable" means no per ceptible false contouring. Figures 2.5(b) through (f) show the results obtained by writing image f to disk (in JPEG format), with q = 50, 25, 1 5, 5, and 0, respectively. For example, the applicable syntax for q = 25 is » imwrite ( f , ' bubbles25 . j pg ' , ' quality ' , 25 ) The image for q = 1 5 [Fig. 2.5(d)] has false contouring that is barely vis ible, but this effect becomes quite pronounced for q = 5 and q = 0. Thus, an acceptable solution with some margin for error is to compress the images with q = 25. In order to get an idea of the compression achieved and to obtain other image file details, we can use function imfinfo, which has the syntax imfinfo filename where filename is the file name of the image stored on disk. For example, >> imfinfo bubbles25 . j pg outputs the following information (note that some fields contain no informa tion in this case): Filename : FileModDate : FileSize : Format : FormatVersion : ' bubbles25 . j pg ' ' 04 -J an - 2003 1 2 : 31 : 26 ' 1 3849 ' j pg ' Width : 714 Height : 682 BitDepth : 8 ColorType : ' grayscale ' FormatSignature : Comment : { } where FileSize is in bytes. The number of bytes in the original image is com puted by multiplying Width by Height by BitDepth and dividing the result by 8. The result is 486948. Dividing this by FileSize gives the compression ratio: (486948/1 3849) = 35. 1 6. This compression ratio was achieved while main taining image quality consistent with the requirements of the application. In addition to the obvious advantages in storage space, this reduction allows the transmission of approximately 35 times the amount of uncompressed data per unit time. The information fields displayed by imfinfo can be captured into a so called structure variable that can be used for subsequent computations. Using the preceding image as an example, and letting K denote the structure variable, we use the syntax >> K = imfinfo ( ' bubbles25 . j pg ' ) ; to store into variable K all the information generated by command imfinfo. Recent versions or MATLAB may show more information in lhc output of imfinfo. particularly for images caplUres using digital cameras. Structures arc discussed in Section 2. 10.7.