(Ebook) Data Science with Python by coll.

- 1. (Ebook) Data Science with Python by coll.install download https://ebooknice.com/product/data-science-with-python-6855552 Download more ebook instantly today at https://ebooknice.com

- 2. Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you Download now and discover formats that fit your needs... Start reading on any device today! (Ebook) Data-Driven SEO with Python: Solve SEO Challenges with Data Science Using Python by Andreas Voniatis ISBN 9781484291757, 1484291751 https://ebooknice.com/product/data-driven-seo-with-python-solve-seo-challenges- with-data-science-using-python-56859340 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Data-Driven SEO with Python: Solve SEO Challenges with Data Science Using Python by Andreas Voniatis ISBN 9781484291757, 9781484291740, 1484291751, 1484291743 https://ebooknice.com/product/data-driven-seo-with-python-solve-seo-challenges- with-data-science-using-python-48293704 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Foundations of Data Science with Python by John M. Shea https://ebooknice.com/product/foundations-of-data-science-with-python-58360476 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Data Science with Python and Dask by Jesse C. Daniel https://ebooknice.com/product/data-science-with-python-and-dask-54973168 ebooknice.com

- 3. (Ebook) Data Science Fundamentals with R, Python, and Open Data by Marco Cremonini ISBN 9781394213245, 1394213247 https://ebooknice.com/product/data-science-fundamentals-with-r-python-and-open- data-56698776 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Python Data Science Handbook: Essential Tools for Working with Data by Jake VanderPlas ISBN 9781491912058, 1491912057 https://ebooknice.com/product/python-data-science-handbook-essential-tools-for- working-with-data-5677824 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Data Science and Analytics with Python by Jesus Rogel-Salazar ISBN 9781498742092, 1498742092 https://ebooknice.com/product/data-science-and-analytics-with-python-6998478 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Data Science Fundamentals with R, Python, and Open Data (for True Epub) by Marco Cremonini ISBN 9781394213269, 1394213263 https://ebooknice.com/product/data-science-fundamentals-with-r-python-and-open- data-for-true-epub-56673172 ebooknice.com (Ebook) Python Data Science Handbook: Essential Tools for Working with Data by Jake VanderPlas ISBN 9781371401412, 9781491912058, 1371401411, 1491912057 https://ebooknice.com/product/python-data-science-handbook-essential-tools-for- working-with-data-6745454 ebooknice.com

- 7. Table of Contents Python: Real-World Data Science Meet Your Course Guide What's so cool about Data Science? Course Structure Course Journey The Course Roadmap and Timeline 1. Course Module 1: Python Fundamentals 1. Introduction and First Steps – Take a Deep Breath A proper introduction Enter the Python About Python Portability Coherence Developer productivity An extensive library Software quality Software integration Satisfaction and enjoyment What are the drawbacks? Who is using Python today? Setting up the environment Python 2 versus Python 3 – the great debate What you need for this course Installing Python Installing IPython Installing additional packages How you can run a Python program Running Python scripts Running the Python interactive shell Running Python as a service Running Python as a GUI application How is Python code organized

- 8. How do we use modules and packages Python's execution model Names and namespaces Scopes Guidelines on how to write good code The Python culture A note on the IDEs 2. Object-oriented Design Introducing object-oriented Objects and classes Specifying attributes and behaviors Data describes objects Behaviors are actions Hiding details and creating the public interface Composition Inheritance Inheritance provides abstraction Multiple inheritance Case study 3. Objects in Python Creating Python classes Adding attributes Making it do something Talking to yourself More arguments Initializing the object Explaining yourself Modules and packages Organizing the modules Absolute imports Relative imports Organizing module contents Who can access my data? Third-party libraries Case study 4. When Objects Are Alike

- 9. Basic inheritance Extending built-ins Overriding and super Multiple inheritance The diamond problem Different sets of arguments Polymorphism Abstract base classes Using an abstract base class Creating an abstract base class Demystifying the magic Case study 5. Expecting the Unexpected Raising exceptions Raising an exception The effects of an exception Handling exceptions The exception hierarchy Defining our own exceptions Case study 6. When to Use Object-oriented Programming Treat objects as objects Adding behavior to class data with properties Properties in detail Decorators – another way to create properties Deciding when to use properties Manager objects Removing duplicate code In practice Case study 7. Python Data Structures Empty objects Tuples and named tuples Named tuples Dictionaries Dictionary use cases

- 10. Using defaultdict Counter Lists Sorting lists Sets Extending built-ins Queues FIFO queues LIFO queues Priority queues Case study 8. Python Object-oriented Shortcuts Python built-in functions The len() function Reversed Enumerate File I/O Placing it in context An alternative to method overloading Default arguments Variable argument lists Unpacking arguments Functions are objects too Using functions as attributes Callable objects Case study 9. Strings and Serialization Strings String manipulation String formatting Escaping braces Keyword arguments Container lookups Object lookups Making it look right Strings are Unicode

- 11. Converting bytes to text Converting text to bytes Mutable byte strings Regular expressions Matching patterns Matching a selection of characters Escaping characters Matching multiple characters Grouping patterns together Getting information from regular expressions Making repeated regular expressions efficient Serializing objects Customizing pickles Serializing web objects Case study 10. The Iterator Pattern Design patterns in brief Iterators The iterator protocol Comprehensions List comprehensions Set and dictionary comprehensions Generator expressions Generators Yield items from another iterable Coroutines Back to log parsing Closing coroutines and throwing exceptions The relationship between coroutines, generators, and functions Case study 11. Python Design Patterns I The decorator pattern A decorator example Decorators in Python The observer pattern

- 12. An observer example The strategy pattern A strategy example Strategy in Python The state pattern A state example State versus strategy State transition as coroutines The singleton pattern Singleton implementation The template pattern A template example 12. Python Design Patterns II The adapter pattern The facade pattern The flyweight pattern The command pattern The abstract factory pattern The composite pattern 13. Testing Object-oriented Programs Why test? Test-driven development Unit testing Assertion methods Reducing boilerplate and cleaning up Organizing and running tests Ignoring broken tests Testing with py.test One way to do setup and cleanup A completely different way to set up variables Skipping tests with py.test Imitating expensive objects How much testing is enough? Case study Implementing it 14. Concurrency

- 13. Threads The many problems with threads Shared memory The global interpreter lock Thread overhead Multiprocessing Multiprocessing pools Queues The problems with multiprocessing Futures AsyncIO AsyncIO in action Reading an AsyncIO future AsyncIO for networking Using executors to wrap blocking code Streams Executors Case study 2. Course Module 2: Data Analysis 1. Introducing Data Analysis and Libraries Data analysis and processing An overview of the libraries in data analysis Python libraries in data analysis NumPy pandas Matplotlib PyMongo The scikit-learn library 2. NumPy Arrays and Vectorized Computation NumPy arrays Data types Array creation Indexing and slicing Fancy indexing Numerical operations on arrays Array functions

- 14. Data processing using arrays Loading and saving data Saving an array Loading an array Linear algebra with NumPy NumPy random numbers 3. Data Analysis with pandas An overview of the pandas package The pandas data structure Series The DataFrame The essential basic functionality Reindexing and altering labels Head and tail Binary operations Functional statistics Function application Sorting Indexing and selecting data Computational tools Working with missing data Advanced uses of pandas for data analysis Hierarchical indexing The Panel data 4. Data Visualization The matplotlib API primer Line properties Figures and subplots Exploring plot types Scatter plots Bar plots Contour plots Histogram plots Legends and annotations Plotting functions with pandas Additional Python data visualization tools

- 15. Bokeh MayaVi 5. Time Series Time series primer Working with date and time objects Resampling time series Downsampling time series data Upsampling time series data Timedeltas Time series plotting 6. Interacting with Databases Interacting with data in text format Reading data from text format Writing data to text format Interacting with data in binary format HDF5 Interacting with data in MongoDB Interacting with data in Redis The simple value List Set Ordered set 7. Data Analysis Application Examples Data munging Cleaning data Filtering Merging data Reshaping data Data aggregation Grouping data 3. Course Module 3: Data Mining 1. Getting Started with Data Mining Introducing data mining A simple affinity analysis example What is affinity analysis? Product recommendations

- 16. Loading the dataset with NumPy Implementing a simple ranking of rules Ranking to find the best rules A simple classification example What is classification? Loading and preparing the dataset Implementing the OneR algorithm Testing the algorithm 2. Classifying with scikit-learn Estimators scikit-learn estimators Nearest neighbors Distance metrics Loading the dataset Moving towards a standard workflow Running the algorithm Setting parameters Preprocessing using pipelines An example Standard preprocessing Putting it all together Pipelines 3. Predicting Sports Winners with Decision Trees Loading the dataset Collecting the data Using pandas to load the dataset Cleaning up the dataset Extracting new features Decision trees Parameters in decision trees Using decision trees Sports outcome prediction Putting it all together Random forests How do ensembles work? Parameters in Random forests Applying Random forests

- 17. Engineering new features 4. Recommending Movies Using Affinity Analysis Affinity analysis Algorithms for affinity analysis Choosing parameters The movie recommendation problem Obtaining the dataset Loading with pandas Sparse data formats The Apriori implementation The Apriori algorithm Implementation Extracting association rules Evaluation 5. Extracting Features with Transformers Feature extraction Representing reality in models Common feature patterns Creating good features Feature selection Selecting the best individual features Feature creation Creating your own transformer The transformer API Implementation details Unit testing Putting it all together 6. Social Media Insight Using Naive Bayes Disambiguation Downloading data from a social network Loading and classifying the dataset Creating a replicable dataset from Twitter Text transformers Bag-of-words N-grams Other features

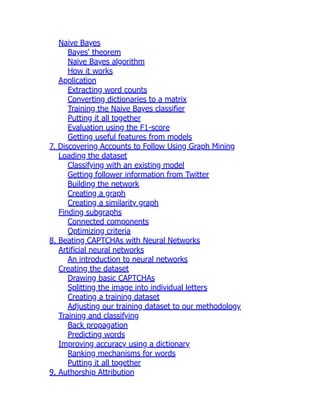

- 18. Naive Bayes Bayes' theorem Naive Bayes algorithm How it works Application Extracting word counts Converting dictionaries to a matrix Training the Naive Bayes classifier Putting it all together Evaluation using the F1-score Getting useful features from models 7. Discovering Accounts to Follow Using Graph Mining Loading the dataset Classifying with an existing model Getting follower information from Twitter Building the network Creating a graph Creating a similarity graph Finding subgraphs Connected components Optimizing criteria 8. Beating CAPTCHAs with Neural Networks Artificial neural networks An introduction to neural networks Creating the dataset Drawing basic CAPTCHAs Splitting the image into individual letters Creating a training dataset Adjusting our training dataset to our methodology Training and classifying Back propagation Predicting words Improving accuracy using a dictionary Ranking mechanisms for words Putting it all together 9. Authorship Attribution

- 19. Attributing documents to authors Applications and use cases Attributing authorship Getting the data Function words Counting function words Classifying with function words Support vector machines Classifying with SVMs Kernels Character n-grams Extracting character n-grams Using the Enron dataset Accessing the Enron dataset Creating a dataset loader Putting it all together Evaluation 10. Clustering News Articles Obtaining news articles Using a Web API to get data Reddit as a data source Getting the data Extracting text from arbitrary websites Finding the stories in arbitrary websites Putting it all together Grouping news articles The k-means algorithm Evaluating the results Extracting topic information from clusters Using clustering algorithms as transformers Clustering ensembles Evidence accumulation How it works Implementation Online learning An introduction to online learning

- 20. Implementation 11. Classifying Objects in Images Using Deep Learning Object classification Application scenario and goals Use cases Deep neural networks Intuition Implementation An introduction to Theano An introduction to Lasagne Implementing neural networks with nolearn GPU optimization When to use GPUs for computation Running our code on a GPU Setting up the environment Application Getting the data Creating the neural network Putting it all together 12. Working with Big Data Big data Application scenario and goals MapReduce Intuition A word count example Hadoop MapReduce Application Getting the data Naive Bayes prediction The mrjob package Extracting the blog posts Training Naive Bayes Putting it all together Training on Amazon's EMR infrastructure 13. Next Steps… Chapter 1 – Getting Started with Data Mining

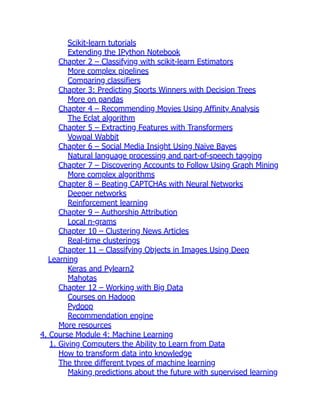

- 21. Scikit-learn tutorials Extending the IPython Notebook Chapter 2 – Classifying with scikit-learn Estimators More complex pipelines Comparing classifiers Chapter 3: Predicting Sports Winners with Decision Trees More on pandas Chapter 4 – Recommending Movies Using Affinity Analysis The Eclat algorithm Chapter 5 – Extracting Features with Transformers Vowpal Wabbit Chapter 6 – Social Media Insight Using Naive Bayes Natural language processing and part-of-speech tagging Chapter 7 – Discovering Accounts to Follow Using Graph Mining More complex algorithms Chapter 8 – Beating CAPTCHAs with Neural Networks Deeper networks Reinforcement learning Chapter 9 – Authorship Attribution Local n-grams Chapter 10 – Clustering News Articles Real-time clusterings Chapter 11 – Classifying Objects in Images Using Deep Learning Keras and Pylearn2 Mahotas Chapter 12 – Working with Big Data Courses on Hadoop Pydoop Recommendation engine More resources 4. Course Module 4: Machine Learning 1. Giving Computers the Ability to Learn from Data How to transform data into knowledge The three different types of machine learning Making predictions about the future with supervised learning

- 22. Classification for predicting class labels Regression for predicting continuous outcomes Solving interactive problems with reinforcement learning Discovering hidden structures with unsupervised learning Finding subgroups with clustering Dimensionality reduction for data compression An introduction to the basic terminology and notations A roadmap for building machine learning systems Preprocessing – getting data into shape Training and selecting a predictive model Evaluating models and predicting unseen data instances Using Python for machine learning 2. Training Machine Learning Algorithms for Classification Artificial neurons – a brief glimpse into the early history of machine learning Implementing a perceptron learning algorithm in Python Training a perceptron model on the Iris dataset Adaptive linear neurons and the convergence of learning Minimizing cost functions with gradient descent Implementing an Adaptive Linear Neuron in Python Large scale machine learning and stochastic gradient descent 3. A Tour of Machine Learning Classifiers Using scikit-learn Choosing a classification algorithm First steps with scikit-learn Training a perceptron via scikit-learn Modeling class probabilities via logistic regression Logistic regression intuition and conditional probabilities Learning the weights of the logistic cost function Training a logistic regression model with scikit-learn Tackling overfitting via regularization Maximum margin classification with support vector machines Maximum margin intuition Dealing with the nonlinearly separable case using slack variables Alternative implementations in scikit-learn

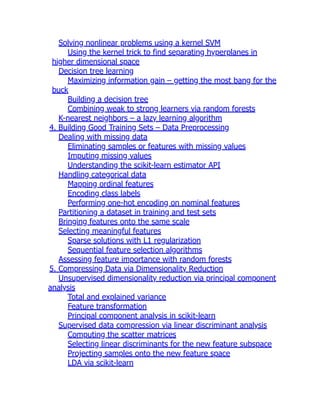

- 23. Solving nonlinear problems using a kernel SVM Using the kernel trick to find separating hyperplanes in higher dimensional space Decision tree learning Maximizing information gain – getting the most bang for the buck Building a decision tree Combining weak to strong learners via random forests K-nearest neighbors – a lazy learning algorithm 4. Building Good Training Sets – Data Preprocessing Dealing with missing data Eliminating samples or features with missing values Imputing missing values Understanding the scikit-learn estimator API Handling categorical data Mapping ordinal features Encoding class labels Performing one-hot encoding on nominal features Partitioning a dataset in training and test sets Bringing features onto the same scale Selecting meaningful features Sparse solutions with L1 regularization Sequential feature selection algorithms Assessing feature importance with random forests 5. Compressing Data via Dimensionality Reduction Unsupervised dimensionality reduction via principal component analysis Total and explained variance Feature transformation Principal component analysis in scikit-learn Supervised data compression via linear discriminant analysis Computing the scatter matrices Selecting linear discriminants for the new feature subspace Projecting samples onto the new feature space LDA via scikit-learn

- 24. Using kernel principal component analysis for nonlinear mappings Kernel functions and the kernel trick Implementing a kernel principal component analysis in Python Example 1 – separating half-moon shapes Example 2 – separating concentric circles Projecting new data points Kernel principal component analysis in scikit-learn 6. Learning Best Practices for Model Evaluation and Hyperparameter Tuning Streamlining workflows with pipelines Loading the Breast Cancer Wisconsin dataset Combining transformers and estimators in a pipeline Using k-fold cross-validation to assess model performance The holdout method K-fold cross-validation Debugging algorithms with learning and validation curves Diagnosing bias and variance problems with learning curves Addressing overfitting and underfitting with validation curves Fine-tuning machine learning models via grid search Tuning hyperparameters via grid search Algorithm selection with nested cross-validation Looking at different performance evaluation metrics Reading a confusion matrix Optimizing the precision and recall of a classification model Plotting a receiver operating characteristic The scoring metrics for multiclass classification 7. Combining Different Models for Ensemble Learning Learning with ensembles Implementing a simple majority vote classifier Combining different algorithms for classification with majority vote Evaluating and tuning the ensemble classifier Bagging – building an ensemble of classifiers from bootstrap samples

- 25. Leveraging weak learners via adaptive boosting 8. Predicting Continuous Target Variables with Regression Analysis Introducing a simple linear regression model Exploring the Housing Dataset Visualizing the important characteristics of a dataset Implementing an ordinary least squares linear regression model Solving regression for regression parameters with gradient descent Estimating the coefficient of a regression model via scikit- learn Fitting a robust regression model using RANSAC Evaluating the performance of linear regression models Using regularized methods for regression Turning a linear regression model into a curve – polynomial regression Modeling nonlinear relationships in the Housing Dataset Dealing with nonlinear relationships using random forests Decision tree regression Random forest regression A. Reflect and Test Yourself! Answers Module 2: Data Analysis Chapter 1: Introducing Data Analysis and Libraries Chapter 2: Object-oriented Design Chapter 3: Data Analysis with pandas Chapter 4: Data Visualization Chapter 5: Time Series Chapter 6: Interacting with Databases Chapter 7: Data Analysis Application Examples Module 3: Data Mining Chapter 1: Getting Started with Data Mining Chapter 2: Classifying with scikit-learn Estimators Chapter 3: Predicting Sports Winners with Decision Trees Chapter 4: Recommending Movies Using Affinity Analysis Chapter 5: Extracting Features with Transformers Chapter 6: Social Media Insight Using Naive Bayes

- 26. Chapter 7: Discovering Accounts to Follow Using Graph Mining Chapter 8: Beating CAPTCHAs with Neural Networks Chapter 9: Authorship Attribution Chapter 10: Clustering News Articles Chapter 11: Classifying Objects in Images Using Deep Learning Chapter 12: Working with Big Data Module 4: Machine Learning Chapter 1: Giving Computers the Ability to Learn from Data Chapter 2: Training Machine Learning Chapter 3: A Tour of Machine Learning Classifiers Using scikit-learn Chapter 4: Building Good Training Sets – Data Preprocessing Chapter 5: Compressing Data via Dimensionality Reduction Chapter 6: Learning Best Practices for Model Evaluation and Hyperparameter Tuning Chapter 7: Combining Different Models for Ensemble Learning Chapter 8: Predicting Continuous Target Variables with Regression Analysis B. Bibliography Index

- 28. Python: Real-World Data Science A course in four modules Unleash the power of Python and its robust data science capabilities with your Course Guide Ankita Thakur Learn to use powerful Python libraries for effective data processing and analysis To contact your Course Guide Email: <[email protected]>

- 29. Meet Your Course Guide Hello and welcome to this Data Science with Python course. You now have a clear pathway from learning Python core features right through to getting acquainted with the concepts and techniques of the data science field—all using Python! This course has been planned and created for you by me Ankita Thakur – I am your Course Guide, and I am here to help you have a great journey along the pathways of learning that I have planned for you. I've developed and created this course for you and you'll be seeing me through the whole journey, offering you my thoughts and ideas behind what you're going to learn next and why I recommend each step. I'll provide tests and quizzes to help you reflect on your learning, and code challenges that will be pitched just right for you through the course. If you have any questions along the way, you can reach out to me over e-mail or telephone and I'll make sure you get everything from the course that we've planned – for you to start your career in the field of data science. Details of how to contact me are included on the first page of this course.

- 30. What's so cool about Data Science? What is Data Science and why is there so much of buzz about this in the world? Is it of great importance? Well, the following sentence will answer all such questions: "This hot new field promises to revolutionize industries from business to government, health care to academia." --The New York Times The world is generating data at an increasing pace. Consumers, sensors, or scientific experiments emit data points every day. In finance, business, administration, and the natural or social sciences, working with data can make up a significant part of the job. Being able to efficiently work with small or large datasets has become a valuable skill. Also, we live in a world of connected things where tons of data is generated and it is humanly impossible to analyze all the incoming data and make decisions. Human decisions are increasingly replaced by decisions made by computers. Thanks to the field of Data Science! Data science has penetrated deeply in our connected world and there is a growing demand in the market for people who not only understand data science algorithms thoroughly, but are also capable of programming these algorithms. A field that is at the intersection of many fields, including data mining, machine learning, and statistics, to name a few. This puts an immense burden on all levels of data scientists; from the one who is aspiring to become a data scientist and those who are currently practitioners in this field. Treating these algorithms as a black box and using them in decision- making systems will lead to counterproductive results. With tons of algorithms and innumerable problems out there, it requires a good

- 31. Another Random Scribd Document with Unrelated Content

- 32. serious danger. Thus, John Hyrcanus destroyed the temple of the Sâmaritans (who also worshiped Jehovah) on Mount Gerizim, and the Jews actually commemorated the event by a semi-festival. Alexander Jannasus, too, carried on wars of conquest against his neighbors. In one of these he took the town of Gaza, and evinced the treatment to be expected from him by letting loose his army on the inhabitants and utterly destroying their city. It was no doubt their unsocial and proud behavior towards all who were not Jews that provoked the heathens to try their temper by so many insults directed to the sensitive point—their religion. Culpable as this was, it must be admitted that it was in some degree the excessive scrupulosity of the Jews in regard to things indifferent in themselves that exposed them to so much annoyance. Had they been content to permit the existence of Hellenic or Roman customs side by side with theirs, they might have been spared the miseries which they subsequently endured. But the Scriptures, from beginning to end, breathed a spirit of fierce and exclusive attachment to Jehovah; he was the only deity; all other objects of adoration were an abomination in his sight. Penetrated with this spirit, the Jews patiently submitted to the yoke of every succeeding authority— Chaldeans, Syrians, Egyptians, Romans—until the stranger presumed to tamper with the national religion. Then their resistance was fierce and obstinate. The great rebellion which broke out in the reign of Antiochus Epiphanes, under the leadership of Mattathias, was provoked by the attempt of that monarch to force Greek institutions on the Jewish people. The glorious dynasty of the Asmoneans were priests as well as kings, and the royal office, indeed, was only assumed by them in the generation after that in which they had borne the priestly office, and as a consequence of the authority derived therefrom. Under the semi-foreign family of the Herods, who supplanted the Asmoneans, and ruled under Roman patronage, as afterwards under the direct government of Rome, it was nothing but actual or suspected aggressions against the national faith that provoked the loudest murmurs or the most determined opposition. It was this faith which had upheld the Jews in their heroic revolt against Syrian innovations. It was this which inspired them to

- 33. support every offshoot of the Asmonean family against the odious Herod. It was this which led them to entreat of Pompey that he would abstain from the violation of the temple; to implore Caligula, at the peril of their lives, not to force his statue upon them; to raise tumults under Cumanus, and finally to burst the bonds of their allegiance to Rome under Gessius Florus. It was this which sustained the war that followed upon that outbreak—a war in which even the unconquerable power of the Roman Empire quailed before the unrivaled skill and courage of this indomitable race; a war of which I do not hesitate to say that it is probably the most wonderful, the most heroic, and the most daring which an oppressed people has ever waged against its tyrants. But against such discipline as that of Rome, and such generals as Vespasian and Titus, success, however brilliant, could be but momentary. The Jewish insurrection was quelled in blood, and the Jewish nationality was extinguished—never to revive. One more desperate effort was indeed made; once more the best legions and the best commanders of the Empire were put in requisition; once more the hopes of the people were inflamed, this time by the supposed appearance of the Messiah, only to be doomed again to a still more cruel disappointment. Jerusalem was razed to the ground; Aelia Capitolina took its place; and on the soil of Aelia Capitolina no Jew might presume to trespass. But if the trials imposed on the faith of this devoted race by the Romans were hard, they were still insignificant compared to those which it had to bear from the Christian nations who inherited from them the dominion of Europe. These nations considered the misfortunes of the Jews as proceeding from the divine vengeance on the crime they had committed against Christ; and lest this vengeance should fail to take effect, they made themselves its willing instruments. No injustice and no persecution could be too bad for those whom God himself so evidently hated. Besides, the Jews had a miserable habit of acquiring wealth; and it was convenient to those who did not share their ability or their industry to plunder them from time to time. But the Jewish race and the Jewish religion survived it all. Tormented, tortured, robbed, put

- 34. to death, hunted from clime to clime; outcasts in every land, strangers in every refuge, the tenacity of their character was proof against every trial, and superior to every temptation. In this unequal combat of the strong against the weak, the synagogue has fairly beaten the Church, and has vindicated for itself that liberty which during centuries of suffering its enemy refused to grant. Eighteen hundred years have passed since the soldiers of Titus burned down the temple, laid Jerusalem in ashes, and scattered to the winds the remaining inhabitants of Judea; but the religion of the Jews is unshaken still; it stands unconquered and unconquerable, whether by the bloodthirsty fury of the legions of Rome, or by the still more bloodthirsty intolerance of the ministers of Christ. Subdivision I.—The Historical Books. It is scarcely necessary to say that no complete account of the contents of the Old Testament can be attempted here. To accomplish anything like a full description of its various parts, and to discuss the numerous critical questions that must arise in connection with such a description, would in itself require a large volume. In a treatise on comparative religion, anything of this kind would be out of place. It is mainly in its comparative aspect that we are concerned with the Bible. Hence many very interesting topics, such, for instance, as the age or authorship of the several books, must be passed over in silence. Tempting as it may be to turn aside to such inquiries, they have no immediate bearing on the subject in hand. Whatever may be the ultimate verdict of Biblical criticism respecting them, the conclusions here reached will remain unaffected. All that I can do is to assume without discussion the results obtained by the most eminent scholars, in so far as they appear to me likely to be permanent. That the Book of Genesis, for example, is not the work of a single writer, but that at least two hands may be distinguished in it; that the Song of Solomon is, as explained both by Renan and Ewald, a drama, and not an effusion of piety; that the latter part of Isaiah is not written by the same prophet who composed the former,

- 35. —are conclusions of criticism which I venture to think may now be taken for granted and made the basis of further reasoning. At the same time I have taken for granted—not as certain, but as likely to be an approximation to the truth—the chronological arrangement of the prophets proposed by Ewald in his great work on that portion of Scripture. Further than this, I believe there are no assumptions of a critical character in the ensuing pages. First, then, it is to be observed that the problems which occupied the writers of the Book of Genesis, and which in their own fashion they attempted to solve, were the same as those which in all ages have engaged the attention of thoughtful men, and which have been dealt with in many other theologies besides that of the Hebrews. The Hebrew solution may or may not be superior in simplicity or grandeur to the solutions of Parsees, Hindus, and others; but the attempt is the same in character, even if the execution be more successful. The authors of Genesis endeavor especially to account for:— 1. The Creation of the Universe. 2. The Origin of Man and Animals. 3. The Introduction of Evil. 4. The Diversity of Languages. Although the fourth of these questions is, so far as I am aware, not a common subject of consideration in popular mythologies, the first three are the standard subjects of primitive theological speculation. Let us begin with the Creation. One of the earliest inquiries that human beings address themselves to when they arrive at the stage of reflection is:—How did this world in which we find ourselves come into being? Out of what elements was it formed? Who made it, and in what way? A natural and obvious reply to such an inquiry is, that a Being of somewhat similar nature to their own, though larger and more powerful, took the materials of which the world is formed and moulded them, as a workman moulds the materials of his handicraft,

- 36. into their present shape. The mental process gone through in reaching this conclusion is simply that of pursuing a familiar analogy in such a manner as to bring the unknown within the range of conceptions applicable to the known. The solution, as will be seen shortly, contrives to satisfy one-half of the problem only by leaving the other half out of consideration. This difficulty, however, does not seem to have occurred to the ancient Hebrew writers who propounded the following history of the Creation of the Universe:— "In the beginning," they say, "God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was desolate and waste, and darkness on the face of the abyss, and the Spirit of God hovering on the face of the waters. And God said: Let there be light, and there was light. And God saw the light that it was good, and God divided between the light and the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And it was Evening, and it was Morning: one day. "And God said: Let there be a vault for separation of the waters, and let it divide between waters and waters." Hereupon he made the vault, and separated the waters above it from those below it. The vault he called Heavens. This was his second day's work. On the third, he separated the dry land from the sea, "and saw that it was good;" besides which he caused the earth to bring forth herbs and fruit-trees. "And God said: Let there be lights in the vault of the heavens to divide between the day and between the night, and let them be for signs and for times and for days and for years." Hereupon he made the sun for the day, the moon for the night, and the stars. "And God put them on the vault of the heavens to give light to the earth, and to rule by day and by night, and to separate between the light and the darkness; and God saw that it was good. And it was evening, and it was morning; the fourth day" (Gen. i. 1- 19). Let us pause a moment here before passing on to the next branch of the subject: the creation of animals and man. The author had two questions before him; how the materials of the universe came into

- 37. being, and how, when in being, they assumed their present forms and relative positions. Of the first he says nothing, unless the first verse be taken to refer to it. But this can scarcely be; for the expression, "God made the heavens and the earth," cannot easily be supposed to refer to the original production of the matter out of which the heavens and the earth were subsequently made. Rather must we take it as a short heading, referring to the creation which is about to be described. And in any case, the manner in which there came to be anything at all out of which heavens and earth could be constructed is not considered. We are left apparently to suppose that matter is coeval with the Deity; for the author never faces the question of its origin, which is the real difficulty in all such cosmogonies as his, but hastens at once to the easier task of describing the separation and classification of materials already in existence. Somewhat similar to the Hebrew legend, both in what it records and in what it omits, is the story of creation as told by the Quichés in America:— "This is the first word and the first speech. There were neither men nor brutes, neither birds, fish, nor crabs, stick nor stone, valley nor mountain, stubble nor forest, nothing but the sky; the face of the land was hidden. There was naught but the silent sea and the sky. There was nothing joined, nor any sound, nor thing that stirred; neither any to do evil, nor to rumble in the heavens, nor a walker on foot; only the silent waters, only the pacified ocean, only it in its calm. Nothing was but stillness, and rest, and darkness, and the night; nothing but the Maker and Moulder, the Hurler, the Bird-Serpent" (M. N. W., p. 196.— Popol Vuh, p. 7). Another cosmogony is derived from the Mixtecs, also aborigines of America:—

- 38. "In the year and in the day of clouds, before ever were either years or days, the world lay in darkness; all things were orderless, and a water covered the slime and the ooze that the earth then was" (M. N. W., p. 196). Two winds are in this myth the agents employed to effect the subsidence of the waters, and the appearance of dry land. In another account, related by some other tribes, the muskrat is the instrument which divides the land from the waters. These myths, as Mr. Brinton, who has collected them, truly remarks, are "not of a construction, but a reconstruction only, and are in that respect altogether similar to the creative myth of the first chapter of Genesis." In the Buddhistic history of the East Mongols, the creation of the world is made, as in Genesis, the starting point of the relation. But the creative forces in this mythology are apparently supposed to be inherent in primeval matter. Hence we have a Lucretian account of the movements of the several parts of the component mass without any consideration of the question how the impulse to these movements was originally given. "In the beginning there arose the external reservoir from three different masses of matter; namely, from the creative air, from the waving water, and from the firm, plastic earth. A strong wind from ten-quarters now brought about the blue atmosphere. A large cloud, pouring down continuous rain, formed the sea. Dry land arose by means of grains of dust collecting on the surface of the ocean, like cream on milk."[91] Although the sacred writings of the Parsees contain no connected account of the creation, yet this void is fully supplied by traditions which have acquired a religious sanction, and have entered into the popular belief. Those traditions are found in the Bundehesh and the Shahnahmeh, works of high authority in the Parsee system. According to them, Ahura-Mazda, the good principle, induced his rival, Agra-Mainyus, the evil principle, to enter into a truce of nine thousand years, foreseeing that by means of this interval he would

- 39. be able to subdue him in the end. Agra-Mainyus, having discovered his blunder, went to the darkest hell, and remained there three thousand years. Ahura-Mazda took advantage of this repose to create the material world. He produced the sky in forty-five days, the water in sixty, the earth in seventy-five, the trees in thirty, the cattle in eighty, and human beings in seventy-five; three hundred and sixty-five days were thus occupied with the business of creation. It will be observed that, though the time taken is longer, the order of production is the same in the Parsee as in the Hebrew legend. This fact tends to confirm the supposition, which will hereafter appear still more probable, of an intimate relation between the two. Always prone to speculation, the Hindus were certain to find in the dark subject of creation abundant materials for their mystic theories. Various explanations are accordingly given in the Rig-Veda. Thus, the following account is found in the tenth Book:— "Let us, in chanted hymns, with praise, declare the births of the gods,—any of us who in this latter age may behold them. Brâhmanaspati blew forth these births like a blacksmith. In the earliest age of the gods, the existent sprang from the non-existent: thereafter the regions sprang from Uttānapad. The earth sprang from Uttānapad, from the earth sprang the regions: Daksha sprang from Aditi, and Aditi from Daksha. Then the gods were born, and drew forth the sun, which was hidden in the ocean" (O. S. T., vol. v. p. 48.—Rig-Veda, x. 72). With higher wisdom, another Vaidik Rishi declares it impossible to know the origin of the universe:— "There was then neither nonentity nor entity: there was no atmosphere, nor sky above. What enveloped [all]? Where, in the receptacle of what, [was it contained]? Was it water, the profound abyss? Death was not then, nor immortality; there was no distinction of day or night. That One breathed calmly, self-supported; there was nothing

- 40. different from, or above, it. In the beginning darkness existed, enveloped in darkness. All this was undistinguishable water. That One which lay void, and wrapped in nothingness, was developed by the power of fervor. Desire first arose in It, which was the primal germ of mind; [and which] sages, searching with their intellect, have discovered in their heart to be the bond which connects entity with nonentity. The ray [or cord] which stretched across these [worlds], was it below or was it above? There were there impregnating powers and mighty forces, a self-supporting principle beneath, and energy aloft. Who knows, who here can declare, whence has sprung, whence, this creation? The gods are subsequent to the development of this [universe]; who then knows whence it arose? From what this creation arose, and whether [any one] made it or not, he who in the highest heaven is its ruler, he verily knows, or even he does not know" (O. S. T., vol. v. p. 356.—Rig-Veda, x. 129). A later narrative ascribes creation to the god Prajapati, who, it is said, having the desire to multiply himself, underwent the requisite austerities, and then produced earth, air, and heaven (A. B., vol. ii. p. 372). We now return to Genesis, which proceeds to its second problem: the creation of living creatures and of man. This is solved in two distinct fashions by two different writers. The first relates that on the fifth day God said, "Let the waters swarm with the swarming of animals having life, and let birds fly to and fro on the earth, on the face of the vault of the heavens." Having thus produced the inhabitants of the ocean and air on the fifth day, he produced those of earth on the sixth. On this day too he made man in his own image, and created them male and female. The whole of his work was now finished, and on the seventh day he enjoyed repose from his creative exertions, for which reason he blessed the seventh day (Gen. 1-ii. 3).

- 41. Here the first account of creation ends; the second begins with a descriptive title at the fourth verse of the second chapter. The writer of this version, unlike his predecessor, instead of ascribing the creation of man to the immediate fiat of Elohim, describes the process as resembling one of manufacture. God formed the human figure out of the dust of the earth, and then blew life into it, a conception drawn from the wide-spread notion of the identity of breath with life. Again the narrator of the second story varies from the narrator of the first about the creation of the sexes. In the first, the male and female are made together. In the second, a deep sleep falls upon the man, during which God takes out a rib from his side and makes the woman out of it. Generally speaking, it may be remarked that the former writer moves in a more transcendental sphere than the latter. He likes to conceive the origin of the world, with all its flora and all its fauna, as arising from the simple power of the word of God. How they arise he never troubles himself to say. The latter is more terrestrial. God with him is like a powerful artist; extremely skilled indeed in dealing with his materials, but nevertheless obliged to adapt his proceedings to their nature and capabilities. This author delights in the concrete and particular; and not only does he aim at relating the order of the creation, but also at making the modus operandi more or less intelligible to his hearers. A somewhat different account of the origin of man is given in the traditions of Samoa, one of the Fiji islands. These traditions also describe an epoch when the earth was covered with water. "Tangaloa, the great Polynesian Jupiter," sent his daughter to find a dry place. After a long time she found a rock. In subsequent visits she reported that the dry land was extending. "He then sent her down with some earth and a creeping plant, as all was barren rock. She continued to visit the earth and return to the skies. Next visit, the plant was spreading. Next time, it was withered and decomposing. Next visit, it swarmed with worms. And the next time, the worms had become men and women! A strange account of

- 42. man's origin!" On which it may be remarked, as a curious psychological phenomenon, tending to illustrate the effects of habit, that the missionary considers it "a strange account of man's origin" which represents God as making him from worms, but readily accepts another in which he is made out of dust. The third question dealt with in Genesis is that of the origin of evil. This is a problem which has engaged the attention and perplexed the minds of many inquirers besides these ancient Hebrews, and for which most religions provide some kind of solution. The manner in which it is treated here is as follows:— When God made Adam, he placed him in a garden full of delights, and especially distinguished by the excellence of its fruit-trees. There was one of these trees, however, the fruit of which he did not wish Adam to eat. He accordingly gave him strict orders on the subject in these words: "Of every tree of the garden thou mayst eat; but of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, of that thou mayst not eat, for on what day thou eatest thereof, thou diest the death" (Gen. ii. 16, 17). This order we must suppose to have been imparted by Adam to Eve, who was not produced until after it had been given. At any rate, we find her fully cognizant of it in the ensuing chapter, where the serpent appears upon the scene and endeavors, only too successfully, to induce her to eat the fruit. After yielding to the temptation herself, she induced her husband to do the like; whereupon both recognized the hitherto unnoticed fact of their nudity, and made themselves aprons of fig-leaves. Shortly after this crisis in their lives God came down to enjoy the cool of the evening in the garden; and Adam and Eve, feeling their guilt, ran to hide themselves among the trees. God called Adam, and the latter replied that he had hidden himself because he was naked. But God at once asked who had told him he was naked. Had he eaten of the forbidden tree? Of course Adam and Eve had to confess, and God then cursed the serpent for his gross misconduct, and punished the man by imposing labor upon him, and the woman by rendering her liable to the pains of childbirth. He also condescended so far as to

- 43. become the first tailor, making garments of skins for Adam and Eve. But though he had thus far got the better of them by his superior strength, he was not without apprehension that they might outwit him still. "And God, the Everlasting, spoke: See, the man is become as one of us, to know good and evil; and now, lest he should stretch out his hand and take also of the tree of life, and eat and live forever! Therefore God, the Everlasting, sent him out of the garden of Eden, to cultivate the ground from which he had been taken" (Gen. iii. 22, 23). And in order to make quite sure that the man should not get hold of the tree of life, a calamity which would have defeated his intention to make him mortal, he guarded the approach to it by means of Cherubim, posted as sentinels with the flame of a sword that turned about. In this way he conceived that he had secured himself against any invasion of his privilege of immortality on the part of the human race. Like the myth of creation, the myth of a happier and brighter age, when men did not suffer from any of the evils that oppress them now, is common, if not universal. Common too, if not equally common, is the notion that they fell from that superior state by contracting the stain of sin. I need scarcely refer to the classical story of a golden age, embodied by Hesiod in his "Works and Days," nor to the fable of Pandora allowing the ills enclosed in the box to escape into the world. But it may be of interest to remark, that the conception of a Paradise was no less familiar to the natives of America than to those of Europe. "When Christopher Columbus," observes Brinton, "fired by the hope of discovering this terrestrial paradise, broke the enchantment of the cloudy sea and found a new world, it was but to light upon the same race of men, deluding themselves with the same hope of earthly joys, the same fiction of a long-lost garden of their youth" (M. N. W., p. 87). Elsewhere he says: "Once again, in the legends of the Mixtecas, we hear the old story repeated of the garden where the first two brothers dwelt.... 'Many trees were there, such as yield flowers and roses, very luscious fruits, divers herbs, and aromatic spices'" (M. N. W., p. 90). Corresponding to the golden age among the Greeks was the Parsee

- 44. conception of the reign of Yima, a mythological monarch who was in immediate and friendly intercourse with Ahura-Mazda. Yima's kingdom is thus described in the Vendidad: "There was there neither quarreling nor disputing; neither stupidity nor violence; neither begging nor imposture; neither poverty nor illness. No unduly large teeth; no form that passes the measure of the body; none of the other marks, which are marks of Agra-Mainyus, that he has made on men" (Av., vol. i. p. 76.—Vendidad, Fargard ii. 116 ff.). In another passage, found in the Khorda-Avesta, not only is the happiness of Yima's time depicted, but it is also distinctly asserted that he fell through sin. "During his rule there was no cold, no heat, no old age, no death, no envy created by the Devas, on account of the absence of lying, previously, before he (himself) began to love lying, untrue speeches. Then, when he began to love lying, untrue speeches, Majesty fled from him visibly with the body of a bird" (Av., vol. iii. p. 175.—Khorda-Avesta, xxxv. 32, 34). More elaborately than in any of these systems is the fall of man described in the mythology of Buddhism. In this religion, as in that of the Jews, man is of divine origin, though after a somewhat different fashion. A spiritual being, or god, fell from one of the upper spheres, to be born in the world of man. Through the progressive increase of this being arose "the six species of living creatures in the three worlds." The most eminent of these species, Man, enjoyed an untold duration of life (another point in which Buddhistic legends resemble those of the Hebrews). Locomotion was carried on through the air; they did not consume impure terrestrial food, but lived on celestial victuals; and propagation, since there was no distinction of sex, was carried on by means of emanation. They did not require sun or moon, for they saw by their own light. Alas! one of these pure beings was tempted by a fool called earth-butter and ate it. The rest followed its example. Hereupon the heavenly food vanished; the race lost their power of going about the sky, and ceased to shine by their own light. This was the origin of the evil of the darkening of the mind. As a consequence of these deeds, sun, moon, and stars appeared. Still greater calamities were in store for

- 45. men. Another, at another time, ate a different kind of food, an example again followed by the rest. In consequence of this, the distinctions of sex were established in them; passion arose; they began to beget children. This was the origin of the evil of sensual love. On a further occasion, one of them ate wild rice, and all lived for a time on wild rice, gathered as it was needed for immediate consumption. But when some foolish fellow took it into his head to collect enough for the following day, the rice ceased to grow without cultivation. This was the origin of the evil of idle carelessness. It being now necessary to cultivate rice, persons began to appropriate and quarrel about land, and even to kill one another. This was the origin of the evil of anger. Again, some who were better off hid their stores from those who were not so well off. This was the origin of the evil of covetousness. In course of time the age of men began to decline so as to be expressible in numbers. It continues gradually to decline until a turning-point arrives, at which it again increases (G. O. M., p. 5-9). Several points of similarity between the Hebrew myth and that just narrated will doubtless occur to the reader. The fall of man is due, in this, as in Genesis, to the eating of a peculiar food by a single person; and this example is followed, in the one case, by the only other inhabitant; in the other, by all. The calamity thus entailed does not terminate in the loss of former pleasures, but extends to the introduction of crime and sexual relations. Eve is cursed by having to bear children; the same misfortune happened to the Buddhist women. Cain quarreled with Abel and killed him; so did the landed proprietors in the Indian legend quarrel with and kill one another. The fourth question which appeared to have engaged the attention of the authors of Genesis was that of the variety of languages. How was it, if all mankind were descended from a single pair, and if again all but the Noachian family had been drowned, that they did not all speak the pure language in which Adam and Eve had conversed with their Creator in Paradise? Embarrassed by their own

- 46. theories, the writers attempted to account for the phenomenon of the diverse modes of speech in use among men by an awkward myth. Men had determined to build a town, with a tower which should reach to heaven. Jehovah, however, came down one day to see what they were about, and was filled with apprehension that, if they succeeded in this undertaking, he might find it impossible to prevent them from carrying out their wishes in other ways also, whatever those wishes might be. So he determined to confound their language, that they might not understand one another, and by this happy contrivance put an end to the construction of the dangerous tower (Gen. xi. 1-9). We have anticipated the course of the narrative in order to consider the solutions offered in Genesis of the four principal problems with which it attempts to deal. We must now return to the point at which we left the parents of the race, namely, immediately after their expulsion from Eden. They now began to beget children rapidly; and Adam's eldest son, Cain, afterwards killed his second son, Abel, for which Jehovah cursed him as he had previously cursed his parents. Adam and Eve had several other children, and (though this is nowhere expressly stated, but only implied) the brothers and sisters united in marriage to carry out the propagation of the species. In course of time, however, the "sons of God" began to admire the beauty of the "daughters of men," and to take wives from among them. Jehovah, indignant at such a scandal, fixed the limits of man's life—which had hitherto been measured by centuries —at 120 years. At the same time there were giants on earth. Now Jehovah saw that the human race was extremely wicked, so much so, that he began to wish he had never created it. To remedy this blunder, however, he determined to destroy it; and in order that the improvement should be thorough, to destroy along with it all cattle, creeping things, and birds, who had not (so far as we are aware,) entered into the same kind of irregular alliances with other species as men. Nevertheless, he had still a lingering fondness for his handiwork, badly as it had turned out; and therefore determined to preserve enough of each kind of animal, man included, to carry on

- 47. the breed without the necessity of resorting a second time to creation. Acting upon this resolve, he ordered an individual named Noah to build an ark of gopher-wood, announcing that he would shortly destroy all flesh, but wished to save Noah and his three sons, with their several wives. He also desired him to take two members of each species of beasts and birds, or, according to another account, seven of each clean beast and bird, and two of each unclean beast; but in any case taking care that each sex should be represented in the ark. When Noah had done all this, the waters came up from below and down from above, and there was an increasing flood for forty days. All terrestrial life but that which floated in the ark was destroyed. At last the waters began to ebb, and finally the ark rested on the 17th day of the 7th month on Mount Ararat. After forty more days Noah sent out a raven and a dove, of which only the dove returned. In seven days he sent the dove again, and it returned, bringing an olive-leaf; and after another week, when he again sent it out, it returned no more. It was not, however, till the 27th of the 2d month of the ensuing year (these chroniclers being very exact about dates) that the earth was dried, and that Noah and his party were able to quit the ark. To commemorate the goodness of God in drowning all the world except himself and his family, Noah erected an altar and offered burnt-offerings of every clean beast and every clean fowl. The effect was instantaneous. So pleased was Jehovah with the "pleasant smell," that he resolved never to destroy all living beings again, though still of opinion that "the imagination of man's heart is evil from his youth" (Gen. vi. 7, 8). The myth of the deluge is very general. The Hebrews have no exclusive property in it. Many different races relate it in different ways. We may easily suppose that the partial deluges to which they must often have been witnesses suggested the notion of a universal deluge, in which not only a few tribes or villages perished, but all the inhabited earth was laid under water; or the memory of some actual flood of unusual dimensions may have survived in the popular mind, and been handed down with traits of exaggeration and distortion

- 48. such as are commonly found in the narratives of events preserved by oral tradition. Let us examine a few instances of the flood-myth. The Fijians relate that the god "Degei was roused every morning by the cooing of a monstrous bird," but that two young men, his grandsons, one day accidentally killed and buried it. Degei having, after some trouble, found the dead body, determined to be avenged. The youths "took refuge with a powerful tribe of carpenters," who built a fence to keep out the god. Unable to take the fence by storm, Degei brought on heavy floods, which rose so high that his grandsons and their friends had to escape in "large bowls that happened to be at hand." They landed at various places; but it is said that the two tribes became extinct (Viti, p. 394). The Greenlanders have "a tolerably distinct tradition" of a flood. They say that all men were drowned excepting one. This one beat with his stick upon the ground and thereby produced a woman (Grönland, p. 246). Kamtschatka has a somewhat similar legend, except that it admits a larger number of survivors. Very many, according to this version, were drowned, and the waves had sunk those who had got into boats; but others took refuge in rafts, binding the trees together to make them. On these they saved themselves with their provisions and all their property. When the waters subsided, the rafts remained on the high mountains (Kamtschatka, p. 273). Among the North Americans "the notion of a universal deluge" was, in the time of the Jesuit De Charlevoix, "rather wide-spread." In one of their stories, told by the Iroquois, all human beings were drowned; and it was necessary, in order to re-populate the earth, to change animals into men (N. F., vol. iii. p. 345). The Tupis of Brazil are supposed to be named after Tupa, the first of men, "who alone survived the flood" (M. N. W., p. 185). Again, "the Peruvians imagined that two destructions had taken place, the first by a famine, the second by a flood; according to some a few

- 49. only escaping, but, after the more widely accepted opinion, accompanied by the absolute extirpation of the race." The present race came from eggs dropped out of heaven (Ibid., p. 213). Several other tribes relate in diverse forms this world-wide story. In one of the versions, found in an old Mexican work, a man and his wife are saved, by the directions of their god, in a hollow cypress. In another, the earth is destroyed by water, because men "did not think nor speak of the Creator who had created them, and who had caused their birth." "Because they had not thought of their Mother and Father, the Heart of Heaven, whose name is Hurakan, therefore the face of the earth grew dark, and a pouring rain commenced, raining by day, raining by night" (Ibid., p. 206 ff.). The diluvian legend appears in a very singular form in India in the Satapatha Brâhmana. There it is stated, that in the basin which was brought to Manu to wash his hands in, there was one morning a small fish. The fish said to him, "Preserve me, I shall save thee." Manu inquired from what it would save him. The fish replied that it would be from a flood which would destroy all creatures. It informed Manu that fishes, while small, were exposed to the risk of being eaten by other fishes; he was therefore to put it first into a jar; then when it grew too large for that, to dig a trench and keep it in that; that when it grew too large for the trench, to carry it to the ocean. Straightway it became a large fish, and said: "Now in such and such a year, then the flood will come; thou shalt therefore construct a ship, and resort to me; thou shalt embark in the ship when the flood rises, and I shall deliver thee from it." Manu took the fish to the sea, and in the year that had been named, "he constructed a ship and resorted to him. When the flood rose, Manu embarked in the ship. The fish swam towards him. He fastened the cable of the ship to the fish's horn. By this means he passed over this northern mountain. The fish said, 'I have delivered thee; fasten the ship to a tree. But lest the water should cut thee off whilst thou art on the mountain, as much as the water subsides, so much shalt thou descend after it.' He accordingly descended after it as much (as it subsided).... Now the flood had swept away all these creatures; so Manu alone was

- 50. left here" (O. S. T., vol. i. p. 183). The story goes on to relate that Manu, being quite alone, produced a woman by "arduous religious rites," and that with this woman, who called herself his daughter, "he begot this offspring, which is this offspring of Manu," that is, the existing human race. After the flood, the history proceeds for some time to narrate the lives of a series of patriarchs, the mythological ancestors of the Hebrew race. Of these the first is Abram, afterwards called Abraham; to whom a solemn promise was made that he was to be the progenitor of a great nation; that Jehovah would bless those who blessed him, and curse those who cursed him; and that in him all generations of the earth should be blessed (Gen. xii. 1-3). When Abraham visited Egypt, he desired his wife Sarah to call herself his sister, fearing lest the Egyptians should kill him for her sake. She did so, and was taken into Pharaoh's harem in consequence of her false statement; but Jehovah plagued Pharaoh, and his house so severely that the truth was discovered, and Sarah was restored to her lawful husband. It is remarkable that Abraham is stated to have subsequently repeated the same contemptible trick, this time alleging by way of excuse that Sarah really was his step-sister; and that Abraham's son, Isaac, is said to have done the same thing in reference to Rebekah (Gen. xii. 10-20, xx., xxvi. 6-11). Abimelech, king of Gerar, who was twice imposed upon by these patriarchs, must have thought it a singular custom of the family thus to pass off their wives as sisters. Apparently, too, both of them were quite prepared to surrender their consorts to the harems of foreign monarchs rather than run the smallest risk in their defense. Abraham, at ninety-nine years of age, was fortunate in all things but one: he had no legitimate heir. But this too was to be given him. Jehovah appeared to him, announced himself as Almighty God, and established with Abraham a solemn covenant. He promised to make him fruitful, to give his posterity the land of Canaan, in which he then was, and to cause Sarah to have a son. At the same time he desired that all males should be circumcized, an operation which was

- 51. forthwith performed on Abraham, his illegitimate son Ishmael, and all the men in his house (Gen. xvii). In due time Sarah had a son whom Abraham named Isaac. But when Isaac was a lad, and all Abraham's hopes of posterity were centered in him as the only child of Sarah, God one day commanded him to sacrifice him as a burnt- offering on a mountain in Moriah. Without a murmur, without a word of inquiry, Abraham prepared to obey this extraordinary injunction, and was only withheld from plunging the sacrificial knife into the bosom of his son by the positive interposition of an angel. Looking about, he perceived a ram caught in a thicket, and offered him as a burnt offering instead of Isaac. For this servile and unintelligent submission, he was rewarded by Jehovah with further promises as to the amazing numbers of his posterity in future times (Gen. xxi. 1-8; xxii. 1-19). The tradition of human sacrifice, thus preserved in the story of Abraham and Isaac, is found also in a curious narrative of the Aitareya Brâhmana. That sacred book also commemorates an important personage, in this instance a king, who had no son. Although he had a hundred wives, yet none of them bore him a male heir. He inquired of his priest, Narada, what were the advantages of having a son, and learned that they were very great. "The father pays a debt in his son, and gains immortality," such was one of the privileges to be obtained by means of a son. The Rishi Narada therefore advised King Harischandra to pray to Varuna for a son, promising at the same time to sacrifice him as soon as he was born. The king did so. "Then a son, Rohita by name, was born to him. Varuna said to him, 'A son is born to thee, sacrifice him to me.' Harischandra said, 'An animal is fit for being sacrificed, when it is more than ten days old. Let him reach this age, then I will sacrifice him to thee. At ten days Varuna again demanded him, but now his father had a fresh excuse, and so postponed the sacrifice from age to age until Rohita had received his full armor." Varuna having again claimed him, Harischandra now said, "Well, my dear, to him who gave thee unto me, I will sacrifice thee now." But Rohita, come to man's estate, had no mind to be sacrificed, and ran away to the

- 52. wilderness. Varuna now caused Harischandra to suffer from dropsy. Rohita, hearing of it, left the forest, and went to a village, where Indra, in disguise, met him and desired him to wander. The advice was repeated every year until Rohita had wandered six years in the forest. This last year he met a poor Rishi, named Ajigarta, who was starving, to whom he offered one hundred cows for one of his three sons as a ransom for himself in the sacrifice to be offered to Varuna. The father having objected to the eldest, and the mother to the youngest, the middle one Sunahsepa, was agreed upon as the ransom, and the hundred cows were paid for him. Rohita presented to his father the boy Sunahsepa, who was accepted by the god with the remark that a Brahman was worth more than a Kshattriya. "Varuna then explained to the king the rites of the Rajasuya sacrifice, at which on the day appointed for the inauguration he replaced the (sacrificial animal) by a man." But at the sacrifice a strange incident occurred. No one could be found willing to bind the victim to the sacrificial post. At last his father offered to do it for another hundred cows. Bound to the stake, no one could be found to kill him. This act also his father undertook to do for a third hundred. "He then whetted his knife and went to kill his son. Sunahsepa then got aware that they were going to butcher him just as if he were no man (but a beast). 'Well,' said he, 'I will seek shelter with the gods.' He applied to Prajapati, who referred him to another god, who did the same; and thus he was driven from god to god through the pantheon, until he came to Ushas, the dawn. However, as he was praising Ushas, his fetters fell off, and Harischandra's belly became smaller; until at the last verse he was free, and Harischandra well." Sunahsepa was now received among the priests as one of themselves, and he sat down by Visvamitra, an eminent Rishi. Ajigarta, his father, requested that he might be returned to him, but Visvamitra refused, "for," he said, "the gods have presented him to me." From that time forward he became Visvamitra's son. At this point, however, Ajigarta himself entreated his son to return to his home, and the answer of the latter is remarkable. "Sunahsepa answered, 'What is not found even in the

- 53. hands of a Shudra, one has seen in thy hand, the knife (to kill thy son); three hundred cows thou hast preferred to me, O Angiras.' Ajigarta then answered, 'O my dear son! I repent of the bad deed I have committed; I blot out this stain! one hundred of the cows shall be thine!' Sunahsepa answered, 'Who once might commit such a sin, may commit the same another time. Thou art still not free from the brutality of a Shudra, for thou hast committed a crime for which no reconciliation exists.' 'Yes, irreconcilable (is this act),' interrupted Visvamitra!" (A. B., p. 460-469.) On the likeness of this story to the Hebrew legend of the intended sacrifice of Isaac, and on the difference between the two, I shall comment elsewhere. From the days of Abraham the history proceeds through a series of patriarchal biographies—those of Isaac and Rebekah, of Jacob and Rachel, of Joseph and his brothers—to the captivity of the Israelites in Egypt under the successor of the monarch whose prime minister Joseph had been. It is at this point that the history of the Hebrews as a distinct nation may be said to begin. The patriarchs belong to universal history. But from the days of the Egyptian captivity it is the fortunes of a peculiar tribe, and afterwards of an independent people that are followed. We have their deliverance from slavery, their progress through the wilderness, their triumphant establishment in their destined home, the rise, decline, and fall of their national greatness, depicted with much graphic power, and intermingled with episodes of the deepest interest. It would not be consistent with the plan or limits of this work to follow the history through its varied details; all we can do is to touch upon it here and there, where the adventures, institutions, or imaginations of the Hebrews present points of contact with those of other nations as recorded in their authorized writings. It was only by the especial favor of Jehovah that the Hebrew slaves were enabled to escape from Egypt at all. That deity appointed a man named Moses as their leader; and, employing him as his mouthpiece, desired Pharaoh to let them go. On Pharaoh's refusal, he visited Egypt with a series of calamities; all of them

- 54. inadequate to the object in view, until at length Pharaoh and all his army were overwhelmed in the Red Sea, which had opened to allow the Israelites to pass. These last now escaped into the wilderness, where, under the guidance of Moses, they wandered for forty years, undergoing all sorts of hardships, before they reached the promised land. During the course of their travels, Jehovah gave Moses ten commandments, which stand out from a mass of other injunctions and enactments, by the solemnity with which they were delivered, and by the extreme importance of their subject-matter. They are reported to have been given to Moses by Jehovah in person on Mount Sinai, in the midst of a very considerable amount of noise and smoke, apparently intended to be impressive. By these laws the Israelites were ordered— 1. To have no other God but Jehovah. 2. To make no image for purposes of worship. 3. Not to take Jehovah's name in vain. 4. Not to work on the Sabbath day. 5. To honor their parents. 6. Not to kill. 7. Not to commit adultery. 8. Not to steal. 9. Not to bear false witness against a neighbor. 10. Not to covet. Concerning these commandments, it may be observed that the acts enjoined or forbidden are of very different characters. Some of the obligations thus imposed are universally binding, and the precepts relating to them form a portion of universal ethics. Others again are of a purely special theological character, and have no application at all except to those who hold certain theological doctrines. Lastly, others command states of mind only, which have no proper place in positive laws enforced under penalties. To illustrate these remarks in detail: the four commandments against killing, stealing, adultery, and calumny are of universal obligation, and though they are far from exhausting the list of actions which a

- 55. moral code should prohibit, yet properly belong to it and are among its most important constituents. But the first, second, third, and fourth commandments presuppose a nation believing in Jehovah as their God; and even with that proviso the fourth, requiring the observance of a day of rest, is purely arbitrary; belonging only to ritual, not to morals. To place it along with prohibitions of murder and theft, is simply to confuse in the minds of hearers the all- important distinction between special observances and universal duties. Again, the fifth and tenth commandments require mere emotional conditions; respect for parents in the one case, absence of covetousness in the other. No doubt both these mental conditions have actions and abstinences from action as their correlatives; but it is with these last that law should deal, and not with the mere states of feeling over which no commandment can exercise the smallest control. Law may forbid us to annoy our neighbor, or do him an injury on account of his wife whom we love, or his estate which we desire to possess; but it is idle to forbid us to wish that the wife or the estate were ours. These errors are avoided in the five fundamental commandments of Buddhism, which relate wholly to matters that, if binding upon any, are binding upon all. They are these:— 1. Not to kill. 2. Not to steal. 3. Not to indulge in illicit pleasures of sex. 4. Not to lie. 5. Not to drink intoxicating liquors.[92] No doubt the fifth is not of equal importance with the rest; yet its intention is simply to put a stop to drunkenness, and this it accomplishes, like teetotal societies, by requiring entire abstinence. Probably in hot climates, and with populations not capable of much self-control, this was the wisest way. The third commandment, as I have presented it, is somewhat vague, but this is because the form in which it is given by the authorities is not always the same.

- 56. Sometimes it appears as a mere prohibition of all unchastity; but the more probable view appears to be that of Burnouf, who interprets it as directed against adultery, in substantial accordance with Alabaster, who renders it as an injunction "not to indulge the passions, so as to invade the legal or natural rights of other men." In the eight principal commandments of the Parsees, the breach of which was to be punished with death, there is the the same confusion of theological and natural duties as in the Hebrew Bible. The Parsees were forbidden— 1. To kill a pure man (i. e., a Parsee). 2. To put out the fire Behram. 3. To throw the impurity from dead bodies into fire or water. 4. To commit adultery. 5. To practice magic or contribute to its being practiced. 6. To throw the impurity of menstruating women into fire or water. 7. To commit sodomy with boys. 8. To commit highway-robbery or suicide (Av., vol. ii. p. lx). Besides these commandments, Jehovah gave his people a vast mass of laws, amounting in fact to a complete criminal code, through his mouthpiece Moses. Among these laws were those which were written on the two tables of stone, commonly though erroneously supposed to have been the ten commandments of the twentieth chapter. The express statement of Exodus forbids such a supposition. It is there stated that when God had finished communing with Moses he gave him "two tables of testimony, tables of stone, written with the finger of God." This most valuable autograph Moses had the folly to break in his anger at finding that the Israelites, led by his brother Aaron, had taken to worshiping a golden calf in his absence (Ex., xxxi. 18, and xxxii. 19). God, however, desired him to prepare other tables like those he had destroyed, and kindly undertook to write upon them the very words that had been on the first. Apparently, however, he only dictated