These portraits show lives that were lived before the Holocaust.

The photographs capture moments of kindness and compassion, of life enjoyed, and the intimate connections that existed before the Holocaust.

The images stand as stark evidence of the deep loss and destruction wrought by the Nazis and their racist collaborators during the Holocaust.

The photographs reflect the humanity of the victims of the Holocaust. They ask us to remember our common humanity, and our responsibility to defend the right of all to live with dignity and in peace.

Beloved

Two photographs give us a glimpse of a little boy, much loved by his family.

Teri Zinger and her son, Yehonatan, in Rozsnyo, former Czechoslovakia, 1936. Credit: Copyright Yad Vashem Photo Archives, Archival Signature 10011/4. Courtesy of Yocheved Chapnik.

The Nazis murdered Yehonatan and his mother, Teri, in the gas chamber in Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940–1945) on 15 June 1944. The fate of Yehonatan’s grandparents is not known.

Yehonatan sits on his grandfather, Itzhak Haim Moshe Lemberger’s knee as his grandfather and grandmother, Yoheved Yolin, encourage him to look at the camera. They sit in the sunlight. Rozsnyo, former Czechoslovakia, 1936. Credit: Copyright Yad Vashem Photo Archives, Archival Signature 10011/5. Courtesy of Yocheved Chapnik.

Brothers and sisters - the Meyer family

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #32868. Courtesy of Yaakov and Jeannette Meyer. Copyright: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The four Meyer children pose on the balcony of their home in 1934 in Bonn, Germany. From left to right: Yaakov, Erika, Herbert, and Theresia. Seated next to Theresia is her husband. Yaakov, the youngest of the four Meyer siblings, was born in 1928. His oldest sibling, Theresia, was born in 1914; brother Herbert in 1918; and sister Erika in 1921.

In 1934, the children’s father, Albert Meyer, was murdered by Nazi thugs. The family fell into poverty. Theresia, her husband, and Erika left for England – Theresia to work as a nurse, and Erika as a maid.

Yaakov left on a Kindertransport in March 1939. His mother, Karolina, took him to the train station. He never saw her again.

Herbert was murdered with his wife in Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940-1945).

Brothers and sisters - the Kornhauser family

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #14678. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Provenance: George Pick.

These photographs show the family of Pal and Aranka (Shatz) Kornhauser.

The first photograph was taken between 1929-1930. It shows the four Kornhauser siblings posing on the beach at Lake Balaton, near Budapest, Hungary. Big brother Endre Kornhauser holds Janos and Tamas in his arms. Below them is their sister, Lilly.

A formal family photograph taken in 1931 in Budapest, [Pest-PilisSolt-Kiskun], Hungary. Pictured from left to right are mother Aranka (Shatz) with Janos, Endre and Lilly. Their father, Pal, sits next to Lilly and Tamas leans next to Pal.

Pal Kornhauser was a lawyer and served as the legal adviser to the German ambassador in Budapest from 1940 to 1944. He was deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz and killed in the spring of 1944.

Endre, his eldest son, was murdered in 1943.

Over 100 members of the extended Kornhauser family perished during the Holocaust.

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 14670. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Provenance: George Pick.

Friends

Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 16713. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Courtesy Yad Vashem.

This photograph taken before 1941 captures a glimpse of the friendship of a group of girls. They are in a yard in the town of Eisiskes, Lithuania.

None of the girls survived the Holocaust.

Every girl in this photograph was murdered by the mobile killing squads – the Einsatzgruppen – on 25–26 September 1941. Of Eisiskes’s 3,500 Jews, only a few dozen survived the Holocaust.

This exhibition was created by the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme, established by Member States of the United Nations through General Assembly Resolution A/RES/60/7 in 2005.

Credits: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

“Please don’t forget us... If you survive, tell the world what happened.”

- Nesse Godin, survivor of Stutthof concentration camp, Germany and a death march

Oral history with Nesse Godin, Washington, D.C. 14 December 1995. In Beth B. Cohen, Case Closed: Holocaust Survivors in Postwar America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2007, p. 157. Courtesy of Beth B. Cohen.

The Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme

The United Nations General Assembly voted unanimously to establish the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme in 2005 to “mobilize civil society for Holocaust remembrance and education, in order to help to prevent future acts of genocide”. The Outreach Programme is an expression of the United Nations’ commitment to counter antisemitism, Holocaust denial and distortion, and to protect the right of all people to live with dignity and in peace.

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 60/7 in 2005 designated 27 January as the annual International Day of Commemoration in memory of the victims of the Holocaust and established the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme. Resolutions adopted in 2007 and in 2022 reiterated the United Nations’ commitment to counter antisemitism and Holocaust distortion and denial.

General Assembly Hall (UN Photo)

Survivors who graciously shared their testimonies with the Outreach Programme:

- Ms. Lyubov Abramovich

- Ms. Inge Auerbacher

- Mr. Yehuda Bacon

- Ms. Elizabeth Bellak

- Mr. Maurice Blik

- Ms. Ella Blumenthal

- Judge Thomas Buergenthal

- Dr. Irene Butter

- Mr. Boris Feldman

- Ms. Rena Finder

- Ms. Ruth Glasberg Gold

- Mr. Zoni Weisz

- Mr. Max Glauben

- Mr. Jacques Grishaver

- Ms. Nesse Godin

- Mr. Kurt Goldberger

- Ms. Margarete Goldberger

- Mr. Yoram Gross

- Mr. Pinchas Gutter

- Ms. Frances Irwin

- Ms. Vered Kater

- Mr. Roman Kent

- Mr. Serge Klarsfeld

- Ms. Gerda Klein

- Mr. Noah Klieger

- Ms. Agnes Kory

- Professor Robert Krell

- Ms. Jona Laks

- Mr. Arthur Langerman

- Congressman Tom Lantos

- Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau

- Ms. Eva Lavi

- Ms. Johanna Liebman

- Mr. Leo Lowy

- Mr. David Mermelstein

- Mr. Dumitru Miclescu

- Judge Theodor Meron

- Ms. Joanna Millan

- Ms. Marianne Muller

- Mr. Shraga Milstein

- Mr. Leon Moed

- Professor Mordecai Paldiel

- Mr. Alex Moskovic

- Mr. Christian Pfeil

- Ms. Hella Pick

- Mr. Jack Polak

- Ms. Rita Prigmore

- Mr. Haim Roet

- Mr. Leonid Rozenberg

- Ms. Irene Shashar

- Rabbi Arthur Schneier

- Dr. Nechama Tec

- Ms. Selma Tennenbaum Rossen

- Dr. Edith Tennenbaum Shapiro

- Mr. Marian Turski

- Madame Simone Veil

- Ms. Agnes Vertes

- Mr. Zoni Weisz

- Ms. Marta Wise

The Global Impact of the Holocaust

A warning to all people of the dangers of hatred, bigotry, racism, and prejudice."

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/76/250

The United Nations was established in response to the horrors of the Second World War and the Holocaust. The Holocaust has had a profound impact on International Human Rights Law, resulting in the United Nations’ adoption of foundational documents in 1948: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights represents the universal recognition that basic rights and fundamental freedoms are inherent to all human beings, inalienable and equally applicable to everyone, and that every one of us is born free and equal in dignity and rights. Whatever our nationality, place of residence, gender, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, language, or any other status, the international community on 10 December 1948 made a commitment to upholding dignity and justice for all of us. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, or Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to enforce its prohibition. It was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in December 1948.

The World That Was

Only one-third of Jewish men, women and children in Europe survived the Holocaust.

Mother and son, Henrietta and Ivan Rechts. 1939 Former Czechoslovakia. They were subsequently deported to Theresienstadt and Auschwitz, where they perished. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #47570. Courtesy of Gabriella Reitler Rosberger, Source Record ID: Collections: 2004.7. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Mother with daughter on swing, Zwickau, Germany, circa 1937. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 64847. Courtesy of Shoshana Loeb. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

We had a family life. I had four grandparents. Family...there were a lot of certainties. But the certainties ended when I was fourteen years old. They never came back again, of course.”

- Frieda Menco-Brommet (1925–2019). Oral history conducted by Debórah Dwork, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, June 1986. Debórah Dwork, “Children With A Star” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), p.7

Two Jewish brothers on vacation in Italy, April 1935. On the left is Paul Barber and his child, and on the right Gyorgy Barber with his infant. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #17193. Courtesy of Charles & Herma Ellenboghen Barber. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Jews had lived as a minority in Europe for two thousand years before Hitler and his Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933. Maintaining Jewish and national identities, Jews were diverse. Some were pious, some secular; some were poor, some working class, others middle class.

After the Nazi regime took control, all Jews caught in their web were at risk. By 1945, six million – two-thirds of Europe's prewar Jewish population – were annihilated, and the life and culture that had existed for millennia irrevocably ruptured.

The Nazis persecuted Europe’s Roma and Sinti communities, murdering some 500,000 - one-third of Europe’s Roma and Sinti population - by war’s end.

Portrait of two Jewish sisters, Budapest, Hungary, circa 1930–1935. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #45560. Courtesy of Provenance: Gabor Kalman Source Record ID: Collections: 2001.335. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Roma family, Tiergarten, Berlin, Germany, 1936. Despite this photograph having been taken in the garden of the "Racial-Hygienic and Heredity Research Centre" in the Reich Health Office, Berlin, and the identity and intention of the photographer unknown, the close-knit nature of the family and their affection and joy shine bright. Credit: Bundesarchiv, R 165 Bild-244-59/Photographer unknown.

Sophie Kimelman poses with her twin cousins holding their dolls, Lvov, Poland, circa 1929–1930. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #65589. Courtesy of Dr. Sophie Kimelman-Rosen. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Children from the Beit Ahavah Children’s Home in class, Berlin, Germany, circa 1922–1930. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #48873. Courtesy of Ayelet Bargur. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Josef Cohn and his grandsons, Leo and Haim, study the Talmud, Hamburg, Germany, circa 1932–1933. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #93800. Courtesy of Noemi Cassutto. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Teenagers at a Purim party, Frankfurt, Germany, circa 1933–1936. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #56413. Courtesy of Walter Wolff. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Elly and Henri Rodrigues (front center) at a birthday party in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 1936. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #96361. Courtesy of Carolyn Stewart. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A group of young Greek Jews in front of a tobacco store, Salonika, Greece, circa 1930-1939. Among those pictured are Yehuda and Miriam Beraha (front row, left). Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #42481. Courtesy of Jack Beraha, Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Members of the ice hockey team of the Jewish sport's club, Hagibor. Prague, former Czechoslovakia, circa 1925–1930. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #65440. Courtesy of Andrea Renner. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A Jewish youth band performs in Belgrade, former Yugoslavia, 1932. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 25106. Courtesy of Gavra Mandil, Source Record ID: Collections: 2002.158. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Fubini family poses by a riverbank, Torino, Italy, circa 1930–1939. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #49040. Courtesy of Franco Fubini. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Members of a French-Hungarian Romani musical band, Lyon, France, circa 1920–1930. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #33341. Courtesy of Rita Prigmore, Source Record ID: Collections: 2004.226.1 Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Greta Stoessler Engel stands next to her horse, Austria, circa 1920–1930. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #42064. Courtesy of Katie Altenberg. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A Jewish family walks down a street in Bialystok, Poland, 22 June 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Photo Archives #79262. Courtesy of Ewa Kracowska. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Holocaust (1933-1945)

Identification and Segregation during the Second World War

The Holocaust was the state-sponsored, ideologically driven persecution and murder of six million Jews across Europe and half a million Roma and Sinti by Nazi Germany (1933–1945) and other racist states. Nazi ideology built upon pre-existing antisemitism and antigypsyism/anti-Roma prejudice. The Nazi regime dismantled the democratic institutions of government and used state mechanisms to put its racist ideology into practice and to justify its abuses of human rights.

Nazi racism demanded the murder of people with disabilities, the forced sterilization of Germans of African descent, the murder of Soviet prisoners of war, and the enslavement of Slavs. The Nazis persecuted all they deemed as regime opponents including political dissidents, those identified as homosexual and lesbian, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

But in the Nazi imagination, Jews loomed as the primary threat. The Nazi government enacted its racist antisemitic agenda and, after 1941, embarked upon the murder of every Jewish child, woman, and man.

This notice states, “This beautiful city Hersbruck, on this gorgeous spot on the Earth, was created only for Germans, and not for Jews. Jews are therefore not welcome here.” Caption: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #74592. Courtesy of John Howell. Source Record ID: Collections: 2002.216.1

Once in power, the Nazis began the process of social and economic disenfranchisement and segregation of Jews in Germany, thus facilitating the growing abuse.

From 1934 on, signs prohibiting Jews from using public spaces including libraries, swimming pools, theatres, cinemas, and park benches appeared throughout Germany and, after the 1938 Anschluss (annexation) of Austria by Germany, in Austria as well.

Once in my lifetime I want to still have a whole loaf of bread. That was my dream.”

– Itka Zygmuntowicz (1926–2020), Survivor of Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940–1945) RG-50.030*0435, Oral history interview with Itka Zygmuntowicz, (1926-2020). Oral History Interviews of the Jeff and Toby Herr Oral History Archive, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

A young baby, Marianne Harpuder (now Price) lies on a park bench in Berlin marked with a “J” to indicate it is only for Jews, 1938, Berlin, Germany. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #62547. Courtesy of Ralph Harpuder.

Suddenly, even my best friends didn’t know me anymore. Antisemitic signs appeared in cities and towns exhorting citizens to view Jews as ‘the Other’”

– Heinz Sandelowski (1921–2000), Rastenburg, Germany, 1933. Oral history conducted by Beth B. Cohen, Providence, R.I., 7 April 1994. Courtesy of Beth B. Cohen.

Class portrait of Jewish children attending Carlebach School in Leipzig, Germany. In 1935, Nazi segregation laws prohibited Jewish children from attending state schools. In Leipzig, the Carlebach School was only Jewish day school available. Among those pictured are Irene Mayer, Esther Heppner, Paula Grunewald, Akiva Zwick and Hans Koch. Erich Petruschke (later Peters) is next to the teacher. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #67856. Courtesy of Irene Lewitt. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Provenance: Irene Lewitt.

In 1935, the Nuremburg Laws provided a racist basis to classify Jews, legalized racist antisemitism, and stripped Jews of their citizenship. The racist laws declared that Jewish people could not have so-called German or Aryan blood, and therefore could not be German citizens. The Laws outlawed marriage or sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews, and further excluded Jews from daily life.

By late 1938, the German State cancelled German Jews’ passports, requiring them to carry new identity cards showing their heritage by the addition of the name Sara or Israel, and with a stamped letter “J.”

Both these additions are evident in Ellen Markiewicz’s passport below:

Ellen Markiewicz and her brother managed to leave Germany in 1939 on a Kindertransport, a rescue effort that brought thousands of children from Germany, Austria, and former Czechoslovakia to France, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Britain. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 61853B. Courtesy of Ellen Gerber. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

After Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, Jews were ordered to wear identifying badges. These badges were decreed in every occupied country. In 1941 this law was extended to Germany. The Nazis intended the badges to humiliate the Jews, and to facilitate the identification of Jews for roundups to ghettos and deportation to camps.

A few examples of identification badges imposed on Jewish people by Nazi decree.

Badges Jews were forced to wear in France, circa 1942 - 1945. Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #1991.70.3. Courtesy of Claudine Cerf. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Badges Jews were forced to wear in Berlin, Germany, circa 1942 - 1945. Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #1991.141.5. Courtesy of Fritz Gluckstein. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Badges Jews were forced to wear in Sveti Ivan Zelina, Croatia, Yugoslavia, circa 1942 - 1945. Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #2002.432.3. Courtesy of Theodora Basch Klayman. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Badges Jews were forced to wear in Belgium. Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #65977. Courtesy of Michel Reynders. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Political “Enemies”

The Nazi government set out to dismantle democracy including shutting down the free press and perverting the legal system. The regime used terror and a network of concentration camps to impose and maintain control. The Nazis banned trade unions and persecuted all whom they considered political opponents including Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Helene Gotthold with her children, Gisela and Gerd. Helene, a Jehovah’s Witness, was arrested for her anti-Nazi views and beheaded in the Ploetzensee prison, 8 December 1944. Her children survived. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives # 20499. Courtesy of Martin Tillmans. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Source Record ID: Collections: 1991.204.

State harassment of men labelled as homosexual, became increasingly brutal. Friedrich-Paul von Groszheim was arrested, humiliated, tortured and forcibly castrated. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives ID5364. Courtesy of Friedrich-Paul von Groszheim, Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Nazi persecution of LGBTIQ+

The Nazi regime radicalized existing laws against male homosexuality persecuting tens of thousands of men and deporting up to 15,000 to concentration camps. The Nazis viewed homosexuality as a threat to a growing "German race". If homosexual men were also identified as Jewish, they faced persecution as Jews and often immediate deportation. While the regime primarily targeted gay men, lesbian women and transgender individuals were also at risk of being reported by neighbours, colleagues, or even family members.

Persons with Disabilities

The Nazis targeted people with disabilities, considering them a threat to so-called racial purity and a financial burden. Nazi propaganda encouraged the German population to view people with disabilities in this way. Between 1939 and 1945, doctors and nurses murdered nearly 300, 000 people with disabilities through starvation, lethal injection, mass shooting or gassing.

Studio portrait of Lotte and Robert Wagemann, c. 1942-1943, Berlin, Germany. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #71708.

Robert Wagemann was born on 23 May 1937 in Mannheim, Germany to parents who were Jehovah's Witnesses. The Nazis persecuted Jehovah’s Witnesses because they refused to take a loyalty oath to Hitler and to serve in the German army. Robert was born shortly after his mother’s release from imprisonment for distributing pamphlets denouncing the Nazi regime. Damage to Robert’s hip during birth went unnoticed until he was almost four. After an unsuccessful attempt to replace Robert’s hip, Robert’s mother Lotte was summoned to bring him for a medical examination. Lotte overheard the doctors discussing “euthanizing” Robert. “Euthanasia” was a Nazi euphemism for murder. Realizing the doctors intended to kill Robert because of his disability, Lotte fled with him to his paternal grandparents.

On his first day of school Robert refused to salute Hitler. His teachers alerted the police. Robert and his mother escaped again and spent the remainder of the war on Robert’s maternal grandparents’ farm.

Robert survived. 10,000 German children with disabilities did not, murdered by Nazi doctors and nurses.

Roma and Sinti

Romani peoples in Europe suffered greatly at the hands of the Nazis and their collaborators. The Nazis viewed Roma as a "biological" threat to the so-called “superior Aryan” people. Building on centuries-old-anti-Roma prejudice and violence, the Nazis stripped Roma and Sinti of their rights, and criminalized and persecuted them. Under the July 1933 “Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Defects,” physicians sterilized Roma and Sinti against their will. Roma and Sinti were subjected to segregation, classification by “racial scientists”, and internment in concentration and labour camps.

We had no rights in any aspect of our lives. We could no longer attend school. We could only go shopping in the hours between 11:00 and 12:00. We could not go to any dances, cinemas, or any public events. In short, we were outcasts. I was then 13 years old.”

- Hermine Horvath, a Roma woman from Burgenland in Austria, describing the situation for her family after the German annexation of Austria in March 1938. Horvath gave this testimony to the Wiener Library in the 1950s.

Racism, persecution, and terror

The Nazi regime’s racism extended to include other minorities deemed inferior especially Roma and Sinti and Germans of African descent. Persecution took many forms, including forced sterilization and incarceration in a concentration camp.

Joseph Muscha Mueller was born in 1932 in Germany to Roma parents. In 1942 two strangers removed him from his classroom. He was forcibly sterilized and deported to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1944. Joseph was smuggled out and survived the remainder of the war hiding in a garden shed. Credit: Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum ID Cards.

Radicalization of Persecution

The November Pogrom (9–10 November 1938) was the first instance of state-organized violence against Jews in Germany, German-annexed Austria and the Sudetenland (part of former Czechoslovakia) and marked a radicalization of Nazi antisemitic policy.

Synagogues, businesses owned by Jews, and Jews’ homes were burned and ransacked. 30,000 men were arrested. Hundreds died. Those who found a way to leave Germany were released.

Emigration from Nazi Germany became more urgent but increasingly difficult, as country after country tightened its immigration policies. Some Jews escaped from Germany to nearby countries where they were trapped when the Second World War began. By 1941, approximately two-thirds of German and Austrian Jews had fled their homelands.

A Jewish-owned business in Berlin, Germany destroyed in the November Pogrom, 1938. 10 November 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #86838. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Exterior view of the old synagogue in Aachen, Germany. The old synagogue was built in 1862. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #29814. Courtesy of Stadtarchiv Aachen Copyright Public Domain.

View of the old synagogue in Aachen, Germany, after its destruction during the November Pogrom, 1938. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #29818. Courtesy of Stadtarchiv Aachen Copyright Public Domain.

Listen here to the impact of the November 1938 Pogrom on 8-year-old Arthur Schneier.

Arthur Schneier. Credit: Rabbi Arthur Scheneir

A bedroom of a flat in Vienna, Austria (taken 10 November 1938). Courtesy Wiener Library and Stadtarchiv Nurnberg.

Listen here to Professor Debórah Dwork describe the impact of the November 1938 Pogrom.

Sites of incarceration and forced labour under the Nazi regime and its allies, 1933-1945

From 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime and its allies created approximately 44,000 sites to confine Jews, political prisoners, POWs, Roma and Sinti, and many others. The map above shows 4,231 locations with one or more sites, including those in North Africa – less than 10% of the total estimated by 2023 by researchers at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. All camps and ghettos in the maps were established by the German forces or Axis-aligned powers. The camps shown in North Africa were established by occupation forces.

Camps (orange dots) could be the size of a city or a single building. Wehrmacht sites (black dots), like some camps, held both POWs and civilians. Ghettos (purple dots) could fill a Jewish neighbourhood or be just a field or barn. At the six SS death camps (red squares – Auschwitz, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, and Treblinka), millions of civilians were murdered, often immediately upon arrival.

Whatever their form, these places collectively held millions of people against their will in brutal, inhumane conditions.

Disclaimer: The designations employed, including geographical names, and the presentation of the materials in the present publication, including the citations, maps and bibliography, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the names and legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries and do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Credit: Present-day physical geography data courtesy of Natural Earth. Projection: Europe Albers Equal Area Conic. Main map and graph by Maja Kruse and Anne Kelly Knowles, 2024. Copyright Anne Kelly Knowles and Maja Kruse. Map of Auschwitz complex and subcamps by Maja Kruse, 2024. Copyright Maja Kruse. This map was originally developed for Sarah Cushman’s forthcoming book, Women in Auschwitz.

Auschwitz camp system

The concentration camp known as Auschwitz has long been a symbol of the Holocaust in its entirety. What many people do not realize is that “Auschwitz” was in fact a complex of three main camps as well as a system of several dozen subcamps. Nor do many know that this system was one of many camp and ghetto systems that in total spanned the width and breadth of Europe. What the Germans called the Auschwitz “Zone of Interest” (Interessengebiet) lay between the Soła and Vistula rivers. It was centered on Auschwitz I, a concentration camp that opened in January 1940 near the Polish town of Oswieçim. (The Nazis cleared the town of its Polish residents to isolate the camp.) The 25-squaremile zone included Auschwitz II-Birkenau, where the Nazis murdered approximately one million Jews and thousands of Romani people, and Auschwitz III-Monowitz, a site intended to manufacture synthetic rubber for industry and the military. At these three main camps and six local subcamps, shown above, tens of thousands of prisoners labored and struggled to survive, including men, women, and children from across Europe: Jews, Romani, political prisoners, Soviet POWs, and German “anti-social” prisoners. The small map in the bottom left shows the location of all 39 subcamps in the Auschwitz system. No still map can convey the dynamism of this system. During the early 1940s it was constantly expanding, adding new sites, structures, purposes, and prisoner populations. These changes reflected the shifting priorities of war and genocide.

Both prisoner experiences and the places they were held were incredibly varied. Some prisoners endured captivity for weeks, others for years; some were shunted from place to place. The sites did not all exist at once, and many facilities changed purpose and location over time.

Seeking Refuge

The Frank family: (left to right): Margot, Otto, Anne, and Edith Frank, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 1941. Courtesy of the Anne Frank Fonds, Basel, Switzerland.

The story of the Frank family illustrates the vulnerability of refugees seeking safety from the Nazis. Otto and Edith Frank and their two young daughters, Margot and Anneliese -Anne - left for Amsterdam, the Netherlands shortly after the Nazis came to power in Germany.

For a few years, it seemed the family would be safe. Otto grew increasingly worried about the stability of the region, and in 1938 applied to the United States for visas for his family. American restrictive immigration policies, and the changing events in Europe destroyed that hope. Germany attacked the Netherlands in 1940 and Otto’s visa applications were destroyed. Unable to leave, Otto created a hiding place in the secret annex of his business’s warehouse. The annex provided shelter for over two years for the Frank family, the van Pels family, and Fritz Pfeffer. They were betrayed in August 1944. Of those who had hidden in the annex, only Otto survived the Holocaust.

Ghettoization

Child in the Lodz ghetto, Poland, circa 1940–1944. Credit: Photograph by Mendel Grossman (1913-1945) who died on a death march, 30 April 1945. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #24635, Courtesy of Moshe Zilbar, Source Record ID: Collections: 2005.214. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Our bread ration has been reduced and vegetables don’t arrive anymore. Hunger is ever more terrifying.”

– Dawid Sierakowiak, (1924–1943), entry dated 18 March 1942.

The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Lodz Ghetto. 18 March 1942. Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

The start of the Second World War in September 1939 was a decisive moment in Nazi anti-Jewish policy. After the Germans conquered Eastern Europe, they concentrated Jews in restricted areas called ghettos; in western Europe they incarcerated Jews in transit camps.

Over 1,100 ghettos existed across Europe, with the largest in Poland. Most ghettos were situated on rail lines that facilitated later mass deportations to killing centers. In many ghettos, Jews sought to maintain vestiges of prewar life, despite squalid conditions. Nonetheless, conditions were a torturous means of annihilation through starvation, slave labour, disease, and executions.

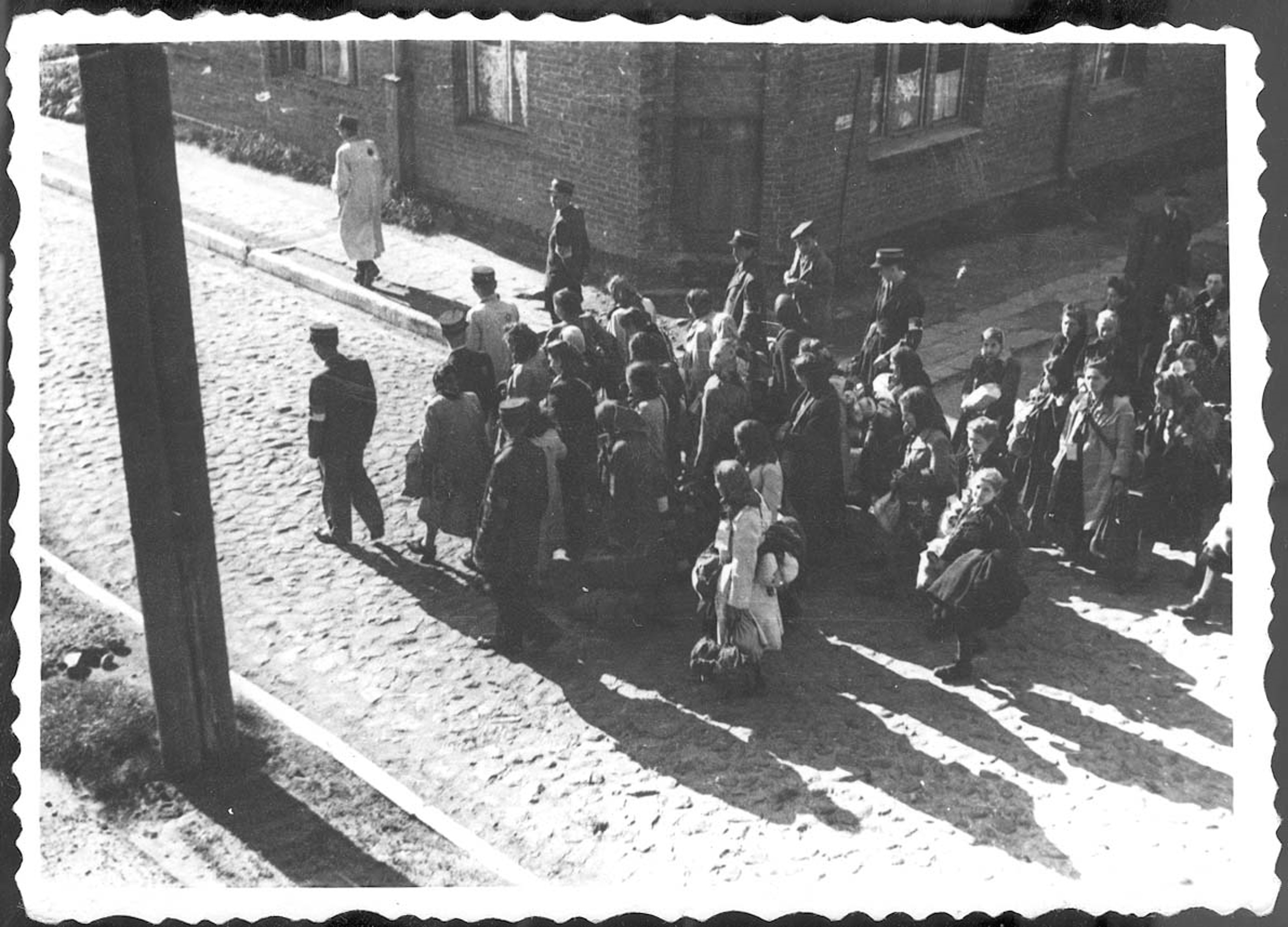

Deportation

Germany and its racist allies began deporting Jews and Roma and Sinti from the ghettos and transit camps to killing centers that had been constructed in occupied Poland.

Rounding up the children from the Lodz ghetto, Poland, for deportation to the Chelmno death camp, Poland, September 1942. None of the children survived. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #50328. Courtesy of Instytut Pamieci Narodowej. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Jewish women and children from Subcarpathian Rus awaiting selection after arrival at Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940-1945), May 1944. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #77255. Courtesy of Yad Vashem (Public Domain). Source Record ID: FA 268/055. Published Source: The Auschwitz Album – Peter Hellman, Random House. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Anna Maria “Setella” Steinbach, a young Romani girl, stares out of a cattle car used for deportation from Westerbork transit camp, the Netherlands, 1944. Setella was murdered with her mother and siblings, in Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940–1945). She was nine years old. Credit: Copyright Yad Vashem Photo Archives, Archival Signature 1475/30.

Systematic mass murder

Mass murder began in June 1941 with Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. As German troops moved into the Soviet Union, mobile killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) followed, massacring Jews in more than 1,500 villages and towns, often in broad daylight in the presence of local witnesses. Nazi policy now encompassed the implementation of the “Final Solution” the Nazi euphemism given for the policy of annihilation of Jewish children, women and men.

To murder more efficiently, the Germans created killing sites in occupied Poland: Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka, Majdanek, and Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940–1945). Most of the people deported to these sites were murdered by poison gas immediately upon arrival.

Portrait of four-year-old Malvina Babat and three-year-old Polina Babat, who were killed at the mass shootings at Babi Yar. c.1940-September 1941. Kiev, former USSR – now Ukraine. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Babi Yar Society. Copyright: Public Domain

They resisted dehumanization

Victims resisted Nazi brutality and dehumanization in many different ways – even in the face of death. These are but a few of the stories we know. Some we will never know.

A portrait of students attending a clandestine school in Mielec ghetto, Poland, 1940. Credit: Yad Vashem Photo Archives, Archival Signature 5187_3. Courtesy of Irena Eber. Copyright Yad Vashem.

Photography as resistance

During the Holocaust, despite the grave risk they faced, Jewish photographers – some professional, some amateurs – recorded what the Nazis and their collaborators perpetrated. These photographers captured on film how the victims responded. The photographs stand as invaluable historical evidence and a form of resistance against the Nazis who wished to remove any trace of Jews.

Shoes left after a deportation from the Kovno ghetto, Lithuania, circa 1943. The photograph was taken by Kovno ghetto survivor, George Kadish. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #81082. Courtesy of George Kadish/Zvi Kadushin, photographer. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Mendel Grossman (1913–1945) imprisoned in Lodz Ghetto in Poland, died on a forced death march, 30 April 1945. Saying goodbye in the Lodz ghetto, Poland, before deportation, September 1942. Photograph by Mendel Grossman. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #23698.Gift of Hana Greenbaum and Shmuel Zilbar in memory of Rozka Grosman Zilbar and Moshe Zilbar (Zilberstein), and Mendel Grossman. Source Record ID: Collections: 2005.214. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Henryk Ross (1910-1991) survived the Lodz ghetto in Poland, and the Holocaust. Deportation of Jews from the Lodz ghetto, Poland, September 1942. Photograph by Lodz ghetto survivor Henryk Ross. Credit: Copyright Yad Vashem Photo Archives, Archival Signature 2631/27.

Vladka Meed – underground resistance courier. False identification card issued in name of Stanislawa Wachalska, that Feigele Peltel (now Vladka Meed) used while serving as a courier for the Jewish underground in Warsaw. 9 October 1943, Warsaw, Poland. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Benjamin (Miedzyrzecki) Meed. Vladka Meed was born Feigele Peltel on 29 December 1921, in Warsaw, Poland. In 1940, she and her family were forced into the Warsaw Ghetto. Her mother, Hanna, her younger sister, Henia, and her little brother, Chaim were among the more than 265,000 Jews the Germans deported to Treblinka death camp between July and September 1942. Left in the ghetto, Feigele joined the Jewish Coordinating Committee. She was able to “pass” as a non-Jewish Pole and moved in and out of the ghetto smuggling illegal literature, correspondence, and weapons into the ghetto, and taking out news about ghetto conditions. Vladka managed to evade detection, torture and death. After the Holocaust, she immigrated to the United States. Vladka died on 22 November 2012.

Faye Schulman (1919-2021), pictured here before the war with her nephew, Schelemale. Lenin, [Belarus; Pinsk] USSR. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Faye Schulman (Faigel Lazebnik). Faye Schulman was born Faigel Lazebnik on 28 November 1919, in Lenin, Eastern Poland (now Western Belarus). When Germany invaded in 1941, Faigel and her family were forced into the Lenin ghetto. In August 1942, the Germans killed 1,850 Jews from the ghetto. The Germans spared Faigel because of her photographic skills. She managed to escape and joined a partisan group. During a subsequent partisan raid of Lenin, Faigle retrieved her photographic equipment. Through her photographs, Faigel documented the suffering and resilience of Jewish victims and partisans. After the war, she immigrated to Canada. She died at the age of 101.

They sought to help

In an increasingly hostile world, a range of individuals, and in a few instances, communities, tried to rescue victims – some through hiding those at risk or smuggling them to safety. Some forged identity documents, some engaged in acts of sabotage, some provided travel documents that could help them escape. These courageous and humane actions were rare. Many local people collaborated willingly. Most were witnesses. Those who sought to help the victims stand as examples of what can be done, even in the face of grave danger.

A few members of the diplomatic community tried to help. Some, like Chiune (Sempo) Sugihara, Japanese consul-general in Kovno, Lithuania, and Aristides De Sousa Mendes, Portuguese consul stationed in Bordeaux, France, defied their own government’s official policy in their efforts to save Jews.

Among those recognized by Yad Vashem, The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, as Righteous Among the Nations are diplomats Carl Lutz, vice-consul of Switzerland in Budapest; Selahattin Ülkümen, Turkish consul-general on the island of Rhodes under German occupation; Ho-Feng Shan, Chinese consul-general in Vienna; Luis Martins de Souza Dantas, Brazil’s Ambassador to France, and Raoul Wallenberg, legation secretary of the Swedish diplomatic mission in Budapest, Hungary.

Whosoever saves a single life, saves an entire universe"

– Mishnah, Sanhedrin 4:5

Per Anger poses in front of a portrait of Raoul Wallenberg in his office in 1985. Second secretary at the Swedish legation in Budapest, Anger worked alongside Raoul Wallenberg to rescue thousands of Hungarian Jews from arrest and deportation. Raoul Wallenberg was captured by the Soviet Army after the war. His fate remains unknown. 1985, Stockholm, Sweden Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Per and Ellena Anger.

The Aftermath

Former women prisoners in bunks in Auschwitz Birkenau German Nazi Concentration and Death Camp (1940–1945). After 27 January 1945. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #31450. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Here I am waiting to be liberated…and everything is gone."

– Sara Kay (1926–2019). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection, Gift of the National Council of Jewish Women Cleveland Section, RG-50.091.0082.

After the Holocaust, survivors confronted a ruptured world. Entire families had been murdered and communities erased. The defeat of the Nazis had not meant the defeat of antisemitism. Survivors unable or unwilling to return to their former homes made their way to displaced persons (DP) camps where they might wait for years before it was possible to immigrate to destinations around the world.

Sherit Hapleita -the Saved Remnant

Drawing upon the Biblical term referring to survivors of the Assyrian destruction of the Kingdom of Israel, Jewish Displaced Persons (DPs) called themselves Sherit Hapleita, the Saved Remnant. They began the process of re-establishing their culture: language, religious observance, Jewish customs, creative expressions. And they documented the atrocities they had survived. The projects and programmes initiated by DPs and supported by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and other organizations, were steps towards reconstituting a community, and reclaiming and constructing an identity.

Even as they moved forward establishing new homes, families, and communities, the memory of the Holocaust cast a long shadow over their lives.

Displaced persons, displaced camps

Anticipating the humanitarian crisis that would follow after the Second World War, the Allied countries established (1943) the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) - the first-ever multinational attempt to co-ordinate such support. Hundreds of displaced persons (DP) camps were set up in Germany, Austria, and Italy.

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) official, Greta Fischer (1910-1988) with Jewish children at Kloster Indersdorf, Germany. Greta Fischer was born in Budišov (former Czechoslovakia) in 1910. She fled to London in 1939. Her parents perished in the Nazi ghetto/camp Terezin. In June 1945, she went to Germany as a member of United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration's Team 182 to work at the International Displaced Person’s Children's Center established at Kloster-Indersdorf. In 1946 the DP Camp was converted to a home for Jewish refugee children from Eastern Europe. Fischer became director of the International Children’s Center Hotel Kronprinz Prien. Credit: UN Archives, S-1058-0001-01-00117

Living and grieving

Holocaust survivors living in the Displaced Persons’ (DP) camps had survived years of extreme violence. The psychological impact of this assault became evident in the DP camps. Even as DPs engaged in daily life – attending educational classes, creating art, celebrating weddings, forming relationships – they mourned all they had lost. Survivors experienced a complex set of emotions that included feelings of powerlessness, bafflement about survival, and fear that the experience of joy was a betrayal of those who did not survive. For some, mourning was perceived as an act of treason against their loved ones as it suggested an acceptance of their deaths. Survivors carried simultaneously the desire to rebuild and reconstitute, and the ache of deep grief, a grief for which some would never find solace.

Bride and groom, Hinda Chilewicz and Welek Luksenburg in the Weiden DP camp, Germany, weep during the recitation of a prayer in memory of their parents, 2 March 1947. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives #28710. Courtesy of William and Helen Lukensenberg. Copyright of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A reminder of our common humanity

To remember the victims of the Holocaust is to remember their humanity, and to defend the rights of all to live in peace and with dignity.

To remember is everyone’s responsibility.

The Holocaust, like all genocides, was not inevitable. Warning signs abounded long before the mass killing, and began with the process of “othering”. The Holocaust cautions us to heed these warning signs and to challenge hatred, bigotry, racism, and prejudice.

We can draw on our knowledge of the past to counter the fear and suspicion spread today through the manipulation of information, hate speech and the distortion of history.

With such knowledge, what will you do?

Credits

Photographs sourced from:

- Anne Frank Fonds, Basel, Switzerland

- Bundesarchiv

- United States Holocaust Memorial and Museum

- Weiner Library

- Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center

With thanks to:

- Mr. Peter Agoos, Designer of Permanent Exhibition, United Nations

- Dr. Beth B. Cohen, Historian

- Professor Debórah Dwork, The Graduate Center – City University of New York (Holocaust scholar and advisor)

- Professor Anne Kelly Knowles, History Department, University of Maine (Holocaust scholar and geographer)

- Ms. Maja Kruse, Interdisciplinary PhD candidate, University of Maine (geographer and map designer)

This exhibit was launched in January 2025